The Geopolitics of the Indian Ocean

A primer on the Indian Ocean and the competition for military and economic influence in this increasingly central driver of the global economy.

The New (and Old) Indian Ocean Economy

On 31st October 2023, the Houthis, an Iranian-backed militia controlling most of north and west Yemen, including the coastline, launched a ballistic missile toward Israel in response to the commencement of its military operations in Gaza. This attack made history as the first “space conflict”: the missile was intercepted above the Kármán line—the boundary between Earth’s atmosphere and space.

On the ground, the Houthis further imposed a naval blockade on the Bab el-Mandeb Strait that guards the Red Sea, one of the world’s critical shipping chokepoints. The Strait handles 12% of world trade, 30% of containerised goods, and 8.6 million barrels of oil on a daily basis. The Houthi blockade has specifically targeted Western and Israeli vessels, resulting in increased associated insurance costs twentyfold. Major shipping firms, such as Maersk and MSC, have rerouted their routes via Africa’s Cape of Good Hope, adding up to 10–14 days to transit times and increasing costs by 40%. The disruption exacerbated inflation for Western consumers by severely impacting trade between East Asia and the West.

The Houthi blockade has exposed the fragility of shipping routes that the global economy relies on. The US, despite claiming the role of global maritime policeman and possessing naval supremacy (for now), has failed to neutralise the Houthi threat or secure the route, with Operation Prosperity Guardian, a US-led coalition to ensure Red Sea trade freedom, expending vast quantities of missiles, drones, and equipment that the US cannot easily replenish owing to its depleted industrial base. Concerns are now mounting within the US Navy regarding insufficient missile production capacity, highlighting a growing vulnerability for modern naval powers: even advanced fleets struggle against asymmetric land-based threats.

Events in the Red Sea have highlighted the increasingly consequential role that the Indian Ocean (of which the Red Sea functions almost like a tributary) plays in the global economy, and how threats to its trade routes reverberate around the world. Even before the Houthis seized power in Yemen’s capital, Sana’a, launched ballistic missiles and drones at Israel, or established a blockade on the Bab al-Mandeb Strait, numerous countries have quietly been ramping up their footprint in the Indian Ocean.

The Indian Ocean is a millennia-old interface between diverse groups and cultures, and a pivotal trade nexus that predates European colonialism. Through Egypt and the Red Sea, Roman merchants traded with India and the Far East. In later centuries, Muslim traders would traverse the “spice routes” on a greater scale. From the 1st century CE, goods such as pepper and cinnamon began to be traded from Asia to Mediterranean markets. The Swahili Coast (Kilwa, Mombasa, and Zanzibar) thrived as a hub for inter-African, Arab, and Indian exchange, facilitating commerce and cultural diffusion. The Omani Empire dominated 18th-century trade, controlling Zanzibar and Gwadar until Britain suppressed the slave trade and annexed key ports. European powers captured trading routes across the Indian Ocean in the Age of Discovery, with Portuguese, Dutch, and English companies and naval powers successively creating zones of influence and integrating the Indian Ocean into a new global economy.

Today, the Indian Ocean is home to more than 2 billion people in the states bordering the ocean, and represents 20% of the world’s water surface. It is fast becoming the centre of the global economy as the bulk of trade volume migrates eastward from the Atlantic, and its fragility is being exploited by various actors, including the US, China, and France, as well as smaller nations such as the UAE and Iran. Small regional states like Djibouti and Somalia are capitalising on their geostrategic position at the mouth of the Red Sea and the eastern gateway to the Indian Ocean on the African continent.

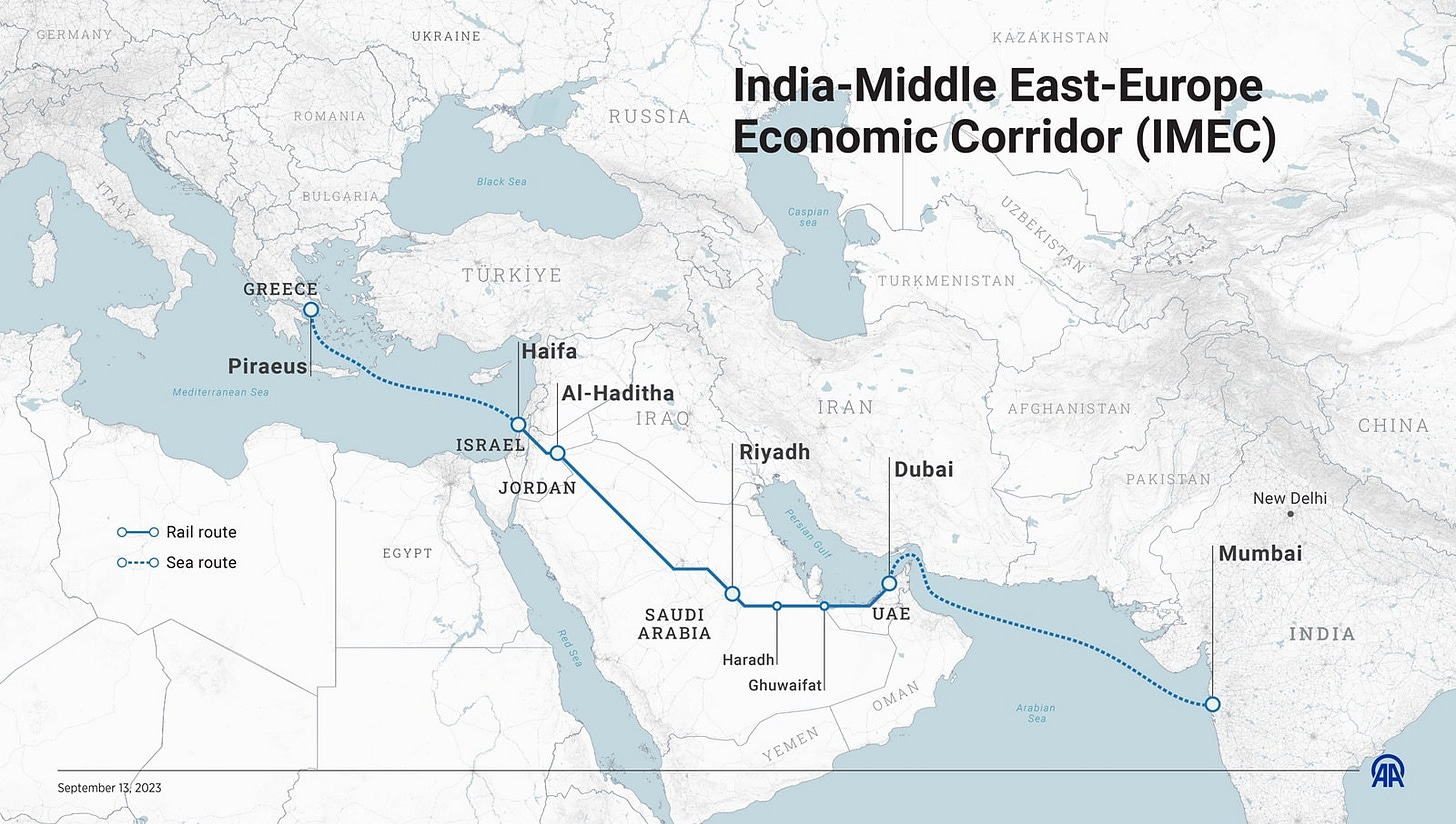

As regional instability mounts (with the Houthi blockade being one of many security issues that the region faces, such as Somali piracy), global and regional powers are competing to carve out zones of interest and develop alternative trade routes around the Red Sea, such as the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC), thereby redrawing the power landscape in the Indian Ocean.

Understanding the geopolitics of the Indian Ocean is crucial to understanding how the next battleground for global influence, trade, and power competition will affect the region itself and the world at large.

This article serves as a basic guide to the present powers, projects, and security challenges in the Indian Ocean, each of which Vizier will explore in detail through future case studies.

The Major Players and Their Interests in the Indian Ocean

The United Arab Emirates

Foremost among these actors is the United Arab Emirates (UAE), which has steadily expanded its influence through an assertive maritime strategy that blends economic expansion with military presence. By developing an extensive port network through companies like DP World (a titan in maritime logistics that Vizier will explore in depth in a later report) and maintaining military bases across the region, the UAE exercises strategic control over critical nodes. These include Berbera Port in Somaliland, de facto authority over Socotra Island since 2014, and military installations in the Maldives and Seychelles.

Having participated actively in the Yemen coalition, the UAE continues to bolster proxies such as Hemedti's Rapid Support Forces (“RSF”) in Sudan and Khalifa Haftar in Libya. Through its partnership with India, the UAE cements its dominance across the western Indian Ocean. In 2022, both countries signed a Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement, aiming to increase bilateral trade to $100 billion annually by 2027. Both countries also enjoy close military and intelligence ties.

Iran

Iran plays a pivotal role in the energy geopolitics of the Indian Ocean. The long-delayed Iran-Pakistan gas pipeline remains stalled due to US sanctions, forcing Pakistan to rely on costlier Qatari LNG, which exacerbates the country's already existing energy crisis. Iran supplies 40% of Iraq’s gas and electricity while selling oil to China at steep discounts. The country hosts Chabahar Port, co-financed by India, which serves as a hub connecting the Indian Ocean to Central Asia and the Middle East.

Nevertheless, US sanctions have severely constrained its economic development. To counterbalance this, Iran has emphasised military power projection as a shield, cultivating influence across the Middle East through proxies and sub-state actors. Iran also possesses significant asymmetrical naval capabilities, augmented by assets such as the repurposed oil tanker Makran, which has been converted into a drone and helicopter carrier, complemented by a formidable ballistic missile arsenal. Iran has been supplying anti-ship ballistic missiles and underwater drones, such as the Ghadir missile class and the Al-Qariaa family of drones, to the Houthis, who became the first group to use these weapons on a battlefield effectively.

Economically, Iran retains significant latent potential, as evidenced during the brief thaw under the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), when French firms such as Renault and Total pursued opportunities to expand into the Iranian market. Following the US withdrawal from the agreement in 2018, however, European investments evaporated, allowing China to secure a deal with Iran, known as the Iran–China 25-year Cooperation Program, signed in 2022. This deal permits China to invest up to $400 billion in Iran for preferential access and a quasi-monopoly in specific sectors in Iran’s domestic market (notably, in telecommunications and railways), and to receive a discount on oil purchases.

Pakistan

Neighbouring Pakistan has failed to realise its latent potential when it comes to exploiting geopolitical possibilities in the Indian Ocean. The China-backed Gwadar Port, developed under the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), was conceived to rival Iran’s Chabahar while serving as the maritime terminus for routes linking western China to the Indian Ocean. A Chronic insurgency in Balochistan and general economic mismanagement have hampered this vision. Though positioned as an equal partnership, Pakistan functions in reality as China’s junior partner due to persistent internal instability. The recent Pakistan-India shooting war saw Pakistani pilots flying Chinese JF-17’s outperform their Indian rivals, bringing down at least two Indian jets, with more unconfirmed. As Pakistan pivots closer to China, Pakistan risks further subordination to Chinese strategic interests, even if it gains security guarantees against India.

China

China itself deploys a multifaceted strategy, recognising the ocean’s critical importance to global trade. Its "String of Pearls" initiative has sought to systematically develop a network of strategic ports stretching from the South China Sea to Africa, with facilities in Sri Lanka’s Hambantota and Djibouti providing logistical and military support for vital sea lanes. China merges military presence with substantial economic investments, particularly in East Africa, where partnerships with Kenya, Ethiopia, Tanzania, and Mozambique focus on energy infrastructure and logistical hubs. Diverging from traditional powers, China secures influence through targeted capital investment rather than overt military occupation. However, with regional instability and growing economic interests, China’s military projection may be compelled to follow suit. China’s PLA Navy is the second-largest in the world, and is significantly larger than its Indian rival. India is therefore careful not to provoke a potential naval race with China.

India

India, as China’s primary regional rival, employs a more nuanced approach. It seeks to counterbalance Chinese expansion through diplomatic engagement and multilateral frameworks, such as the Quad alliance among the United States, Japan, Australia, and India. Despite these ambitions, India’s naval capabilities remain constrained, operating only one aircraft carrier with limited power projection beyond its Exclusive Economic Zone. It compensates through strategic partnerships, such as its relations with the UAE through the I2U2 Initiative (which also includes Israel and the US), and leverages the sheer size of the Indian landmass and its central position in the Indian Ocean, connecting all major trade routes.

The United Kingdom

The United Kingdom’s presence now operates mainly in the symbolic shadow of its imperial past. Post-Brexit, Britain lacks the economic heft to counter China’s expanding footprint. Still, it sustains its relevance through intelligence networks, such as the Five Eyes alliance, particularly by leveraging partnerships with Australia and the United States for maritime domain awareness. However, the puzzling transfer of the Chagos Islands, the kingdom’s main base in the region, to Mauritius has further degraded its power projection.

France

France aspires to lead a collective "maritime NATO," utilising bases in the French island territories of Réunion and Mayotte, as well as a partnership with Djibouti to patrol vast exclusive economic zones and conduct anti-piracy operations. France is doubling down on this strategy through defence pacts with India and the UAE, including joint exercises that solidify what has become one of the region’s most consequential security partnerships.

The United States

The US maintains military primacy via strategic hubs in Diego Garcia, Bahrain, and Guam, securing vital chokepoints. Economically, however, it trails China’s Belt and Road Initiative across Africa and South Asia. The Quad alliance—uniting the US, India, Japan, and Australia—boasts naval coordination but lacks cohesive economic countermeasures to Beijing’s influence, a vulnerability underscored by Australia’s continued dependence on Chinese energy imports.

African States

In the western Indian Ocean, East Africa has emerged as a strategic battleground, with its resource wealth attracting foreign powers that have long been deterred by instability. Somalia’s fragmentation has enabled external actors to back rival factions: Turkiye has become a crucial partner to Mogadishu, the seat of the Somali federal government, training government forces, gaining access to exclusive offshore energy exploration rights, and now intends to build a ‘space port’. Conversely, the UAE champions the increasingly autonomous state of Somaliland that seeks distance from Mogadishu. Sudan, meanwhile, has entertained Russian naval ambitions, though plans for a Red Sea base remain stalled.

Ethiopia, Africa’s second-most populous nation and landlocked since 1998, has secured port access deals with Somaliland and Djibouti. However, these come with geopolitical compromises: Berbera Port is backed by the UAE, while Djibouti leans heavily on Chinese influence.

Small states like Djibouti have become critical linchpins for the regional security strategies of several major military powers, hosting no less than seven foreign bases—including those of the US, China, France, and Japan—to essentially extract rents from their position at the entrance to the Red Sea. Somaliland appears to emulate this model, trading political concessions to the UAE for international recognition. Recent rumours regarding the potential displacement of Gaza’s population to Somaliland, despite US and Israeli objections to these claims, show the relationships bartering influence for power.

South Africa, once a regional leader, has diminished into geopolitical obscurity. However, its position at the Cape of Good Hope enables it to benefit from instability in the Red Sea, as shipping redirects south around the African continent instead.

Oceania

Further east, the Strait of Malacca retains its status as the world’s most critical maritime chokepoint, surpassing even that of the Bab al-Mandeb Strait, which handles nearly 30% of global trade. Singapore dominates this artery as both a logistics hub and host of a US naval base. Through special economic zones in Johor, Malaysia seeks to capitalise on Singapore’s efficiency constraints via collaborative industrial projects. Its northern neighbour, Thailand, is undertaking a proposed Kra Canal project that offers a potential alternative route.

Australia, frequently overlooked, functions as a latent force in the region. Despite its vast maritime territory, significant power projection capabilities remain underdeveloped. However, the AUKUS agreement, which will furnish nuclear-powered submarines, albeit at considerable cost, coupled with its role in the Five Eyes intelligence alliance, suggests potential as a southern anchor for US-led containment strategies in the Indo-Pacific.

Strategic Projects in the Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean, to date, lacks a truly integrated economic architecture that could transform the region and its nations into the new global centre of the world economy. Competition has primarily been restricted to cultivating political influence or military projection, rather than economic integration. That is beginning to change as a raft of strategic projects is being put into motion to capitalise on the Indian Ocean’s growing position as a key driver of the global economy.

At the Bab al-Mandeb Strait—the Red Sea’s narrow southern gateway—Houthi militant attacks have severely disrupted maritime activity. In response, regional powers are advancing land-based alternatives, such as the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC), designed to connect Haifa Port in Israel with India via Jordan, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE). This corridor serves as a contingency against maritime disruption and aligns with Saudi Vision 2030 and India’s resilient trade objectives. Saudi Arabia’s $500 billion NEOM project further adds impetus for the IMEC project.

Deep-sea mining looms as a critical frontier. The Indian Ocean seabed holds polymetallic nodules rich in cobalt, nickel, and rare earth elements—vital for green energy transitions. China leads exploration in international waters with robots capable of mining at depths of 4,000 metres, while India and France focus on securing resources within their Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs).

Digitally, the Indian Ocean has become an invisible battleground. With 95% of global data traffic traversing undersea cables, digital connectivity holds strategic paramountcy. China’s "Digital Silk Road" is expanding its cable networks to Pakistan, Kenya, and France, while the US, India, and Japan are collaborating on secure cable projects to counter Chinese surveillance risks, primarily to safeguard their interests.

The Indian Ocean also lies at the epicentre of an intensifying scramble for natural resources. Mozambique has attracted over $60 billion in LNG investments from firms like TotalEnergies and ExxonMobil, yet jihadist insurgencies jeopardise these operations. Somalia sits atop estimated oil reserves of 30 billion barrels but remains paralysed by political chaos, deterring foreign investment. South Sudan, meanwhile, is progressing with a Chinese-backed pipeline to Kenya’s Lamu Port, bypassing instability in Sudan.

Despite controlling the Suez Canal, Egypt lacks a major Red Sea port or special economic zone comparable to Tanger Med on the Mediterranean. This gap has spurred the urgent development of Ain Sokhna Port. However, Egypt remains vulnerable to security issues, such as the Houthi blockade, which prevents it from having direct access to the Indian Ocean.

For landlocked Central Asian states, access to the Indian Ocean remains imperative. China’s China-Pakistan Economic Corridor aims to connect its western provinces to Gwadar Port, yet Baloch insurgencies and political volatility in Pakistan hinder progress. Meanwhile, Iran’s Chabahar Port—backed by India and Russia—offers an alternative route, though US sanctions persistently delay its development. Russia concurrently recalibrates its southern strategy, eyeing Afghanistan’s $1–3 trillion mineral wealth as feedstock for Chinese industry and exploring naval facilities in Sudan and Mozambique, despite uncertain prospects.

Mediterranean developments increasingly shape the Indian Ocean’s geostrategic calculus. Turkiye’s "Blue Homeland" doctrine drives naval expansion into Libya and Somalia, countering Egyptian and Greek interests, while its 2024 pursuit of rocket-testing facilities signals ambitions in aerospace dominance. Synergies between Mediterranean and Indian Ocean ports also emerge: Morocco’s Tangier Med—already linked to East Asia—plans new routes to Vietnam, Indonesia, and Australia, potentially rerouting 15% of Suez-bound traffic through collaborative ventures, such as the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor.

Africa plays a critical role in this contest. China’s quiet economic conquest continues in mineral-rich Central Africa, where it dominates cobalt extraction in the Democratic Republic of Congo and finances trans-African railways to bypass US-aligned South Africa. These railways aim to unlock Congolese resources and create supply chains that are sanctioned-proof, illustrating how infrastructure becomes the backbone of twenty-first-century influence. As these vectors converge, the Indian Ocean’s status as a contested nexus of power, where naval might, resource control, and digital frontiers collide, only intensifies.

These projects, rivalries, and security challenges demonstrate the Indian Ocean’s increasing centrality to global trade, security, and technological infrastructure as state and non-state actors vie for dominance.

A Great Game

A new "Great Game" is indeed underway, marked by China’s deliberate, quiet expansion via its String of Pearls strategy. This approach sidesteps traditional conquest, leveraging ports, pipelines, and debt to entrench influence. In response, the United States and India have formed counter-alliances, such as the Quad and AUKUS, aimed at containing Beijing’s ambitions. Yet this rivalry risks fragmenting trade routes along political lines, imperilling the global economy.

Simultaneously, assertive middle powers intensify the contest: the UAE establishes a commercial port empire, Turkiye expands its influence across the Horn of Africa, and Iran employs asymmetric tactics to maintain regional relevance. These actors show that power is no longer monopolised by superpowers alone. Even small states in East Africa, such as Djibouti, leverage their geography to extract concessions from rival powers, including the US, China, and the UAE. Non-state actors further exploit vacuums; the Houthis’ disruption of Bab al-Mandeb exemplifies how land-based militancy can militarise once-secure sea lanes, exposing the limits of naval supremacy.

The scramble for resources is intensifying: African LNG reserves and deep-sea mining for critical minerals are becoming flashpoints in the race for energy security and dominance in green technology. Digital infrastructure is forming another frontier in this contest. Subsea cables—carrying 95% of global data—and rival satellite systems (India’s NAVIC, China’s BeiDou) enable both connectivity and surveillance, transforming the ocean floor into an invisible arena of influence.

While trade networks promise prosperity, they remain threatened by strategic rivalries. The US commands the waves militarily, yet China’s infrastructural foothold may yield more enduring leverage. Ports like Berbera or Gwadar symbolise globalisation’s paradox: hubs of commerce encircled by piracy, insurgency, or extremism.

Whoever masters these contradictions will not only dominate the Indian Ocean but may well shape the future of the global economy.