Meloni and Italy’s Neo-Atlanticist Turn

Giorgia Meloni has defied critics as she restores Italy’s position as a Mediterranean power, a more active EU member, and a bridge between Western and Eastern powers.

For decades, Italy was regarded as the “sick man of Europe”, plagued by recurring economic crises, chronic political instability, and major migratory challenges. However, in recent years, the tide appears to have turned. Under the leadership of Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni, Italy is now seeking to position itself as a central player on the European stage, even as a strategic leader within the European Union (EU).

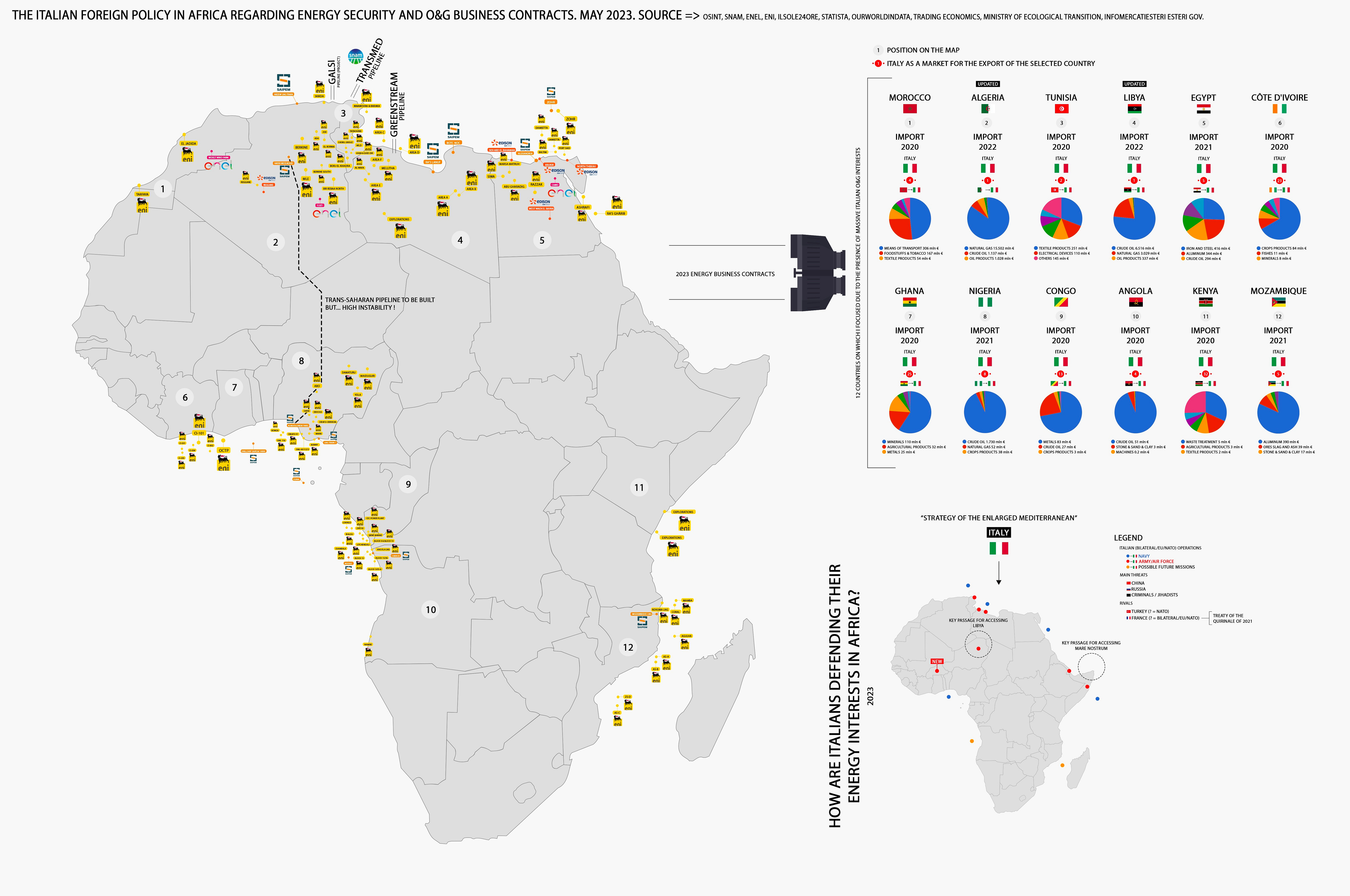

This ambitious repositioning comes with a clear objective: to assert its influence in what Rome now refers to as its “enlarged Mediterranean” – a region extending not only across the traditional Mediterranean basin, but stretching from the Strait of Gibraltar to the Persian Gulf. Italy aims to safeguard its economic, energy, and geopolitical interests in the region while playing an active role in managing migration flows, security crises, and economic partnerships.

The Mattei Plan

During her inaugural speech in October 2022, Giorgia Meloni surprised many observers by announcing the implementation of a “Mattei Plan”, named after Enrico Mattei, the founder of Italy’s national oil company, ENI. This choice was far from trivial: it signalled a powerful ideological foundation underpinning the new Italian Prime Minister’s vision of foreign policy, particularly concerning the MENA region, as well as her conception of national economic and energy sovereignty. This return to the legacy of Mattei reflects a desire to reposition Italy as an active and indispensable Mediterranean power.

In the aftermath of the Second World War, Italy was in ruins. Its economy relied heavily on imported coal and oil, burdening its trade balance and hampering industrial reconstruction. In 1945, the National Liberation Committee tasked Enrico Mattei, a prominent figure within the Christian Democracy (DC) party, with the liquidation of AGIP, the state-owned oil company. Unexpectedly, Mattei refused to dismantle the company. Instead, he viewed it as a strategic lever essential to restoring the country’s energy sovereignty and reviving its industrial base.

Defying the instructions he had received, Mattei restructured AGIP and launched exploration campaigns across the Italian territory. He discovered significant natural gas reserves in the Po Valley near Milan. This gas would go on to heat Italian homes and power the northern industrial economy, at costs well below those of imported fuels. Buoyed by this success, Mattei convinced the government to establish ENI (Ente Nazionale Idrocarburi) in 1952 – a public company to which he granted a monopoly over national energy policy.

But Mattei’s ambitions extended well beyond Italy’s borders. He understood that national energy independence could not be secured through domestic resources alone. ENI was soon engaged in an ambitious strategy to penetrate foreign oil markets. Very quickly, Mattei came into conflict with the interests of the major Anglo-American oil conglomerates – Exxon, Shell, BP, and others – collectively known as the “Seven Sisters”, a term Mattei himself popularised to highlight their quasi-cartel-like dominance.

To challenge them, he proposed a radically new partnership model to oil-producing countries. Rather than the traditional, exploitative rent system, Mattei offered a fair revenue-sharing arrangement: 75% for the producing state, 25% for ENI, with all exploration costs borne by the Italian company. This model, combining economic pragmatism with recognition of the sovereignty of southern nations, marked a historic break with prevailing norms.

Egypt, under Gamal Abdel Nasser, was the first to accept the offer, followed by the Shah’s Iran after the ousting of Prime Minister Mossadegh. ENI subsequently established operations in Libya, Tunisia, Morocco, Iraq, and Jordan. Mattei’s engagement went far beyond extraction contracts: he proposed gradual transfers of technology and know-how, aiming to support the industrial development of partner countries.

It was in Algeria, however, that Mattei and ENI would play a decisive role. During the height of their war of independence against France, Mattei openly supported the Algerian resistance, the FLN (National Liberation Front). Mattei provided strategic backing to the Algerian independence movement and helped the FLN negotiate internationally, offered logistical and legal support, and shared intelligence on Algeria’s hydrocarbon resources. ENI also trained future executives of Sonatrach, the national oil company created after independence.

This assertive support for decolonisation was rooted in a vision shared by a strand of Christian Democracy: that of a third-worldist neo-Atlanticism. According to this doctrine, Italy, by virtue of its geography, history, and cultural ties, has a particular vocation to act as a bridge with the Global South, especially the Arab world, while remaining a loyal member of the Western bloc. The ultimate goal was to make Rome a strategic intermediary between Europe and the Arab world, thereby making Italy indispensable and able to influence both the EU and NATO.

Italy’s Lost Decades

In the 1990s, Italy experienced an economic crisis marked by public debt reaching 110% of GDP, a prolonged economic slowdown, and a growing loss of public trust in institutions. The Christian Democracy party, the cornerstone of Italian politics since the post-war period, was swept away by a massive corruption scandal (the "Mani Pulite" operation), which led to its dissolution, as well as that of the entire parliament. This political earthquake brought an end to the First Republic and ushered in a prolonged era of instability.

Silvio Berlusconi, a media magnate, emerged as a dominant figure on the political scene, governing as Prime Minister between 1994-1995, 2001-2006, then 2008-2011, alternating in power with Romano Prodi. Both pursued austerity policies to meet the Maastricht criteria and facilitate Italy’s entry into the eurozone. Euro adoption became the overriding goal of successive governments, even at the expense of social and industrial policy.

In 2001, Berlusconi returned to power for a second term with a more assertive agenda. He broke with Italy’s long-standing pro-Arab tradition, historically supported by the Vatican and certain Christian Democratic circles, and instead adopted a neo-conservative, pro-American, and pro-Israeli stance. He aligned Italy with NATO’s military campaigns in Iraq and Afghanistan, signalling a major strategic shift. On the European stage, Rome struggled to assert itself against the Franco-German tandem. Berlusconi attempted to chart an alternative course by strengthening ties with Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, whose bid to join the EU he supported.

He also pursued a pragmatic foreign policy towards Libya. During a historic visit to Rome by Muammar Gaddafi in 2008, Berlusconi signed an agreement offering symbolic reparations for Italy’s colonial past in exchange for significant Libyan investments in Italy. He also lobbied the Bush administration for the lifting of sanctions against Tripoli. In so doing, Berlusconi aimed to reposition Italy as a strategic bridge between Europe and the Arab world.

However, the 2008 financial crisis exposed the structural weaknesses of the Italian economy. Reluctant to launch large-scale interventions for fear of worsening the national debt, Berlusconi allowed the economy to stagnate. By 2011, at the height of the sovereign debt crisis, the situation became untenable. Under intense pressure from financial markets and European partners, he was forced to resign. A technocratic government led by Mario Monti took over and implemented harsh austerity measures, which stifled any prospect of economic recovery.

During this period, Italy’s influence in the MENA region (Middle East and North Africa) receded somewhat. This decline can be attributed to several factors, including growing competition from other European powers, such as France and Germany, and the increasing involvement of non-European actors like China, Russia and Turkey – all of which reshaped regional geopolitical dynamics. Nevertheless, Italy maintained significant diplomatic and economic ties with key regional players.

Prior to the imposition of international sanctions related to Iran’s nuclear programme, Italy had been the Islamic Republic’s leading European trading partner. Bilateral trade between the two countries totalled around €7 billion per year, largely concentrated in energy, industrial machinery, and infrastructure, sectors in which Italian firms possessed internationally recognised expertise.

At the same time, Italy remained Egypt’s foremost European partner, sustaining robust economic links in the areas of natural gas, oil, industrial equipment, and construction. The presence of major Italian companies such as ENI bolstered this strategic cooperation. Italy maintained a close political dialogue with Cairo, particularly on issues of security, counterterrorism, and migration management.

In 2018, a populist shift occurred: the anti-establishment Five Star Movement (left-wing populist) formed a coalition with Matteo Salvini’s far-right League. Giuseppe Conte became Prime Minister. His government adopted a foreign policy that leaned towards Russia and China while displaying open hostility towards the EU. One symbolic move was Italy’s accession to China’s “Belt and Road Initiative”, making it the first G7 country to do so (Italy would later pull out in 2023). Anti-EU and anti-migrant rhetoric became central to government discourse. Weakened by years of cuts to public services, particularly in healthcare, Italy was one of the hardest-hit countries during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Since 1994, successive austerity policies, combined with a steady decline in public investment in research and development, have hindered innovation and the modernisation of Italy’s productive sector. Berlusconi’s economic strategy, focused on cost competitiveness rather than quality or added value, exacerbated this lag. While Germany and France poured investment into R&D and high-tech industries, Italy saw its productivity stagnate.

With the adoption of the euro, the country lost the ability to devalue its currency to restore price competitiveness, a tool it had historically relied on. As a result, Italian products, particularly in the manufacturing sector, became too expensive compared to those from emerging economies with weaker currencies and lower labour costs. This imbalance weakened Italy’s exports and widened the gap between itself and its European peers.

However, a turning point began to take shape in the 2010s. In 2016, Prime Minister Matteo Renzi launched the "Industria 4.0" plan, a strategic initiative aimed at modernising the industrial sector through digitalisation and automation. With generous tax credits and investment incentives, the plan enabled many Italian businesses, including SMEs, to invest in new technologies, artificial intelligence, and robotics.

This shift yielded tangible results: Italy is now one of the European countries with the highest number of industrial robots installed, second only to Germany. This positive momentum reflects a paradigm shift: the state has begun to support the transition towards an economic model based on innovation, high value-added production, and industrial specialisation.

Mario Draghi: The Architect of a New Italy

In 2021, the coalition government led by Giuseppe Conte collapsed under the weight of internal tensions between the Five Star Movement, Matteo Salvini’s League, and the Democratic Party. To break the deadlock, President Sergio Mattarella turned to Mario Draghi, former Governor of the European Central Bank and a figure of international repute. Tasked with forming a government of national unity, Draghi succeeded in assembling a broad parliamentary majority, spanning from the moderate left to the right, with the notable exception of Fratelli d’Italia, Meloni’s party.

His appointment marked a decisive break with the political drift and chronic instability that had plagued Italy over the preceding three decades. Draghi embodied a return to a structured, technocratic foreign policy firmly anchored in Euro-Atlantic institutions. From the outset, he expressed a clear intention to restore Italy’s central role within both European and Mediterranean affairs, while also reinforcing its commitment to NATO. This orientation followed the tradition of post-war Italian neo-Atlanticism: a pragmatic diplomacy rooted in strategic interests, particularly in the Mediterranean basin.

A powerful symbol of this shift came with his first official visit abroad to Libya in March 2021, only weeks after taking office. In Tripoli, he declared his desire to "rebuild an old friendship" and to reactivate bilateral cooperation in the areas of security, energy, and migration management. The visit confirmed his ambition to make the "wider Mediterranean", stretching from Gibraltar to the Gulf, a strategic priority for Italy.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 further consolidated this orientation. Draghi quickly positioned himself among the most resolute European leaders in response to Moscow. He gave unreserved support to economic sanctions against Russian assets in Europe and provided both military and humanitarian aid to Ukraine. Aware of Italy’s energy dependence on Russian gas, Draghi swiftly launched a diversification strategy. Within months, Algeria overtook Russia as Italy’s primary gas supplier. This energy realignment was accompanied by a strengthening of bilateral ties with Algiers, in the framework of a strategic partnership.

On the diplomatic front, Draghi broke with the unbalanced bilateralism of the Conte era, especially regarding China and Russia, in favour of a more openly multilateral approach, firmly rooted in the values of the EU and NATO.

The Draghi government restored Italy’s central role in regional geopolitical dynamics, particularly in the Mediterranean, while reaffirming its European and Atlantic commitments during a time of overlapping crises.

Appointed President of the Council of Ministers in February 2021, Draghi assumed leadership at a critical juncture. Italy, hard hit by the COVID-19 pandemic, was facing a prolonged economic slowdown, worsened by decades of political instability, stagnant productivity, and chronic underinvestment. Against this backdrop, the EU allocated Italy an unprecedented €209 billion through the Next Generation EU recovery plan – a mix of grants and loans spread over six years. Italy was the plan’s largest beneficiary, underlining the country’s strategic importance for the eurozone’s stability.

Draghi viewed this financial windfall not as a mere safety net but as a once-in-a-generation opportunity for structural transformation. He deliberately broke with the austerity-driven policies that had dominated Italian governance since the 1990s, under governments such as those of Prodi, Berlusconi, and Monti. Instead, he adopted a neo-Keynesian approach focused on reviving public investment and activating sustainable growth levers.

His plan was built upon several core pillars: energy transition, technological innovation, digitalisation of the public administration, and human capital development. A significant portion of the funds was allocated to renewable energy, the modernisation of railway infrastructure, the construction of smart networks, and improved energy efficiency in both public and private buildings. Draghi’s ambition was not only to accelerate the decarbonisation of the economy, but also to position Italy as a key player in Europe’s ecological transition.

In the realm of innovation, grants were introduced to stimulate private sector investment in research and development (R&D), a field neglected for decades.

Draghi also initiated reform of the public administration, aiming to make it more efficient, digital, and accessible. This endeavour sought to reduce the bureaucratic red tape that hinders investment and burdens businesses, particularly small and medium-sized enterprises. At the same time, efforts were made to improve access to education, vocational training, and youth employment.

Mindful of the Italian economy’s over-reliance on a limited number of European trade partners, Draghi also sought to diversify export markets by strengthening economic ties with North Africa, the Middle East, and Asia. His goal was to build a more resilient, outward-facing economy, less vulnerable to external shocks.

Thanks to this ambitious recovery strategy, Draghi gave Italy a renewed long-term vision focused on innovation, sustainability, and strategic integration into major global dynamics.

Meloni Expands the Mattei Plan

Following deep divisions within his governing coalition, Draghi tendered his resignation in July 2022, after just a year and a half at the helm of the Italian government. Yet, his term was widely praised, both within Italy and abroad. His technocratic style, economic rigour, and international stature helped restore Italy’s credibility on the European and global stage. Despite his enduring popularity and a widely recognised positive legacy, Draghi chose to step down in the face of ongoing political instability.

The snap elections that followed resulted in the victory of Giorgia Meloni and her party Fratelli d’Italia, leading a right-wing coalition that also included Matteo Salvini’s League and Forza Italia, the political heir to Berlusconism. Her rise to power sparked serious concern across European and international circles, due to her nationalist, conservative, and at times eurosceptic rhetoric. However, Meloni swiftly defied the most alarmist predictions.

From the early days of her premiership, she adopted a pragmatic tone, distancing herself from stereotypes of an Italy at odds with Brussels or NATO. Her first official visit was telling: she travelled to Brussels to meet Ursula von der Leyen, thereby signalling her commitment to European institutions. Far from overturning Mario Draghi’s legacy, she embraced his main economic, diplomatic, and strategic priorities.

Draghi, in fact, remained an unofficial adviser, and several of his close collaborators stayed in office, chief among them Giancarlo Giorgetti, who was retained as Minister of the Economy. A moderate respected by the markets, Giorgetti was named Finance Minister of the Year in 2025. Under their guidance, Italy maintained a stable economic policy blending fiscal discipline, investment-led recovery, and innovation.

This pragmatism bore fruit: between 2022 and 2023, Italy recorded one of the highest growth rates at 5% among G7 nations. It made full use of the EU’s Next Generation EU recovery fund, from which Draghi had secured a record €209 billion. These funds were heavily invested in green infrastructure, research, the energy transition, and administrative reform. Breaking decisively with decades of austerity, Italy emerged as one of Europe’s leading advocates of productive public investment.

This momentum also enabled a rapid industrial transformation. As a result, Italy became the world’s fourth-largest exporter, surpassing South Korea and the United Kingdom, and asserted leadership in key sectors such as precision engineering, intermediate goods, pharmaceuticals, agri-food, and luxury goods.

Politically, since Angela Merkel’s departure, Meloni’s Italy has managed to assert itself as a leading power within the EU. While Germany has struggled to define a coherent new direction under Olaf Scholz, and France has faced growing diplomatic isolation, Rome has become a central voice in major debates, from migration and energy to defence and EU enlargement. Meloni combines close ties with Washington with a capacity for autonomous initiative, allowing her to be heard in Brussels, Berlin, and Paris alike.

On the international stage, Meloni extended Italy’s projection strategy in the wider Mediterranean. This became the heart of the Mattei Plan, an ambitious programme of economic, energy, and migration cooperation with Africa. Initially launched with nine African countries, the plan expanded to fourteen, most of them French-speaking, where ENI, Italy’s energy giant, already had a strong presence.

Taking advantage of diplomatic tensions with Paris, Italy stepped up its investments and became Algeria’s top gas client, securing its energy supply while expanding its political influence. In Tunisia, Italy forged a strategic partnership with President Kais Saied, combining investment and infrastructure projects (such as the Elmed power cable and fibre-optic networks), IMF-backed assistance, and migration cooperation. Italy is now Tunisia’s largest foreign investor, having created over 80,000 direct jobs.

In Libya, Italy plays the role of mediator between the eastern authorities (led by General Khalifa Haftar, centred in Benghazi) and the Tripoli government (the Grand National Assembly – or GNA), while maintaining a limited military presence to help stabilise the region and safeguard the Greenstream gas pipeline.

Economic and strategic ties with Turkey have deepened. Bilateral trade has reached €30 billion, with a target of €40 billion in the short term. A joint venture between Leonardo and Baykar in drone technology highlights this growing military cooperation, and Baykar also acquired Piaggio Aerospace.

Italy has also made inroads into the Gulf. With the United Arab Emirates, Rome has signed agreements worth €40 billion, including a joint venture between Fincantieri and EDGE, data centre projects with ENI and Khazna, and cybersecurity cooperation. With Saudi Arabia, €10 billion in agreements are under negotiation, covering shipbuilding (Fincantieri) and aerospace (Leonardo), while Riyadh has joined the GCAP programme – the sixth-generation fighter jet project led by Japan, the United Kingdom, and Italy.

Rome also hosted the fifth round of negotiations on Iran’s nuclear programme between the United States and Iran, moving beyond bilateral economic relations into hot diplomacy.

Italy as a Middle Power

After decades of diplomatic drift, Rome is attempting a strategic repositioning to reshape both Italy’s internal balance and its international stature. This shift began under Mario Draghi, whose European prestige and market credibility as the former President of the European Central Bank restored Italy’s voice on the international stage. He deliberately broke with the legacy of thirty years of tactical retreat, embedding Italy in a new diplomatic framework that aligned with Western priorities while asserting national interests, particularly in the Mediterranean.

Despite emerging from a radical right once marked by Euroscepticism, Giorgia Meloni has faithfully continued along this path. More than mere pragmatic convenience, her decision to uphold Draghi’s diplomatic and economic framework reflects a new strategic awareness: that Italy can only wield influence in the world by acting as a bridge between Europe and the East, between North and South, between Brussels, Washington, and the capitals of Africa and the Middle East. The continuity between Draghi and Meloni is not paradoxical, but a demonstration of the Italian state’s longer-term interests prevailing over technocratic or culture-war political divides.

This neo-Atlanticist pivot has earned Italy renewed credibility within the EU and has enabled Rome to reposition itself as a central player in European energy policy in the wake of its decoupling from Moscow. Italy has strengthened industrial alliances, particularly in defence and high-tech sectors. And above all, it returned Italy to the heart of European affairs, at a time when Germany’s post-Merkel leadership remains undefined, and France grows increasingly isolated on Mediterranean issues.

Italian neo-Atlanticism is a reinvention of Rome’s role as a pivotal power, connecting continents, blocs, and spheres of influence. In a Europe still searching for direction, Italy, against all odds, has forged its own compass.