Syria Unlocks a New Age of Middle Eastern Rail

The Middle East could be connected overland for the first time in a century, with trains running between Istanbul and Muscat.

The first Middle Eastern rail transport was initiated under the Ottoman Empire with landmark projects like the Yafa-Jerusalem line in 1892, followed by the Hejaz Railway and the Berlin-Baghdad line. At the heart of these imperial arteries was Syria. However, a century of political fragmentation following WWI, conflict, and neglect led to the near-total collapse of this network, severing vital links across the region.

While post-independence Syria made significant domestic expansions in rail capacity throughout the 20th century, the post-2011 Revolution and war devastated its infrastructure. Syria's liberation from the Assad regime in December 2024 and its collaboration with Türkiye to restore and upgrade its railways offer a transformative opportunity to establish a high-capacity ‘Middle East Railroad’ (MER) that connects the entire Sunni Corridor running through Türkiye, Syria, Jordan, and the GCC.

This rail bridge promises substantial economic revitalisation for Syria (especially Aleppo and eastern regions), geopolitical gains for Türkiye and GCC states, and enhanced regional integration, while threatening Suez Canal revenues for Egypt and challenging Israel's security strategy; however, its realisation hinges on overcoming significant financing, electricity, security, and coordination challenges.

The History of Levantine Rail

The opening of the Yafa to Jerusalem railway in 1892 marked the beginning of rail transport in the Levant, then part of the Ottoman Empire. Until 1892, the Ottomans had already laid over 2,900 km of track in Anatolia, and over 2000 km in their Balkan territories. Over the subsequent two decades, rail construction in the Levant boomed. In 1895, a French company completed work on a Beirut-Damascus-Daraa line, designed to export agricultural produce from the Hauran region to Europe. By 1902, the Beirut-Damascus line had been connected with a north-south line running from Hama, through Homs and Baalbek. In 1906, the Damascus-Hama line was extended to Aleppo, and in 1911, French engineers completed a line from Homs to Tripoli, connecting the agricultural regions of west-central Syria to the Mediterranean. Western Syria’s main urban centres were now connected by rail, and Damascus and Homs enjoyed direct rail access to their ‘natural’ ports, Beirut and Tripoli, respectively.

In March 1900, Sultan Abdulhamid II ordered the construction of the Hijaz Railway from Damascus to the holy cities of Mecca and Madina. This route was not only intended to reduce travel times for Muslim pilgrims but also to reinforce Ottoman control over the Arabian Peninsula. As the first railway project funded and managed principally by the Ottoman Empire, it also served as a showcase of Ottoman state capacity and as a potent symbol of the sultan-caliph’s religious legitimacy. By the time WWI brought a halt to construction, the tracks had reached Madina, and a branch to Palestine had been added, reducing what had once been a perilous 40-day journey from Damascus to Madina by camel to a five-day trip in the relative comfort and safety of a train carriage. Syria had become a crucial trans-regional transport hub in the empire.

If the Hejaz Railway displayed Syria’s centrality in North-South transport, the Berlin-Baghdad Railway brought out the centrality of Syria – particularly Aleppo, the preeminent commercial hub of the Levant, and the Jazira (Upper Mesopotamia) – in East-West connections. Despite its name, the Berlin-Baghdad railway was intended to connect Hamburg, on the Baltic Sea, with Basra via Istanbul, Aleppo, and Baghdad. The German Kaiser’s ambitious project aimed to facilitate his empire’s access to Iraq’s vast, untapped oil reserves and to create a route to the Indian Ocean that bypassed the British-controlled Suez Canal. While this ambition was never realised due to WWI, British colonial administrators in Iraq and, subsequently, an independent Iraqi state continued work on the line. In 1940, trains were running from Baghdad to Istanbul via Aleppo. Eventually, in 1968, the line was extended to Basra.

Nonetheless, after promising beginnings, the century since the end of WWI has been marked by the decline of international rail connectivity in the Middle East due to war, political fracturing, and negligence. During WWI, the southern portion of the Hejaz Railway was taken permanently out of operation due to extensive sabotage by the anti-Ottoman rebels of Sharif Hussein. The Saudi state that later emerged in the Arabian Peninsula did not restore the line as its oil-based economy had little use for trains. As a result, the Jordanian line south of Amman became redundant and slowly disappeared into the desert.

Subsequently, the creation of Israel in 1948 severed Egypt and Palestine from rail connections to the rest of the Arab world, while the Lebanese Civil War (1975-1990) brought an end to Syrian-Lebanese rail connections. In Syria and Iraq, the mutual hostility of Baathist rivals Hafez Al-Assad and Saddam Hussein brought an end to regular passenger rail between Iraq and Syria. Rail freight was later disrupted by the invasion of Iraq in 2003 and the rise of ISIS. Cool relations between Jordan and Syria in the Hafez Al-Assad era, combined with a lack of economic incentives, resulted in the decline of the Damascus-Amman portion of the Hejaz Railway. The only interstate rail connection that persisted after WWI was that between Syria and Türkiye, principally for freight transport. However, services have been suspended since 2011 with the start of the Syrian Revolution.

Before then, Syria made substantial progress in domestic rail following independence from France in 1946. In 1968, a railway line was opened between Tartus and the Lebanese border to facilitate trade with Tripoli and Beirut. In 1973, work was completed on the railway connecting Aleppo to Deir Al-Zour via Tabqa and Raqqa. Three years later, Deir Al-Zour was connected by rail to Qamishli, which sat on the old Berlin-Baghdad route. 1975 heralded arguably the most significant development in Syrian rail, when the Aleppo-Latakia line was completed, re-establishing the old commercial hub’s direct link to the Mediterranean. In 1980, a freight railway was built between Palmyra and Homs to facilitate the shipment of phosphates to Tartus. Finally, in 1992, a coastal railway linking Tartus and Latakia was opened. By 2011, Syria’s total rail network length stood at 2,552 km, roughly 200 km longer than that of its larger neighbour, Iraq. After the fall of the Assad regime, over 80% of Syria’s rail network is currently out of service, having been heavily degraded by acts of sabotage and theft since 2011.

Reviving Regional Rail Interconnectivity

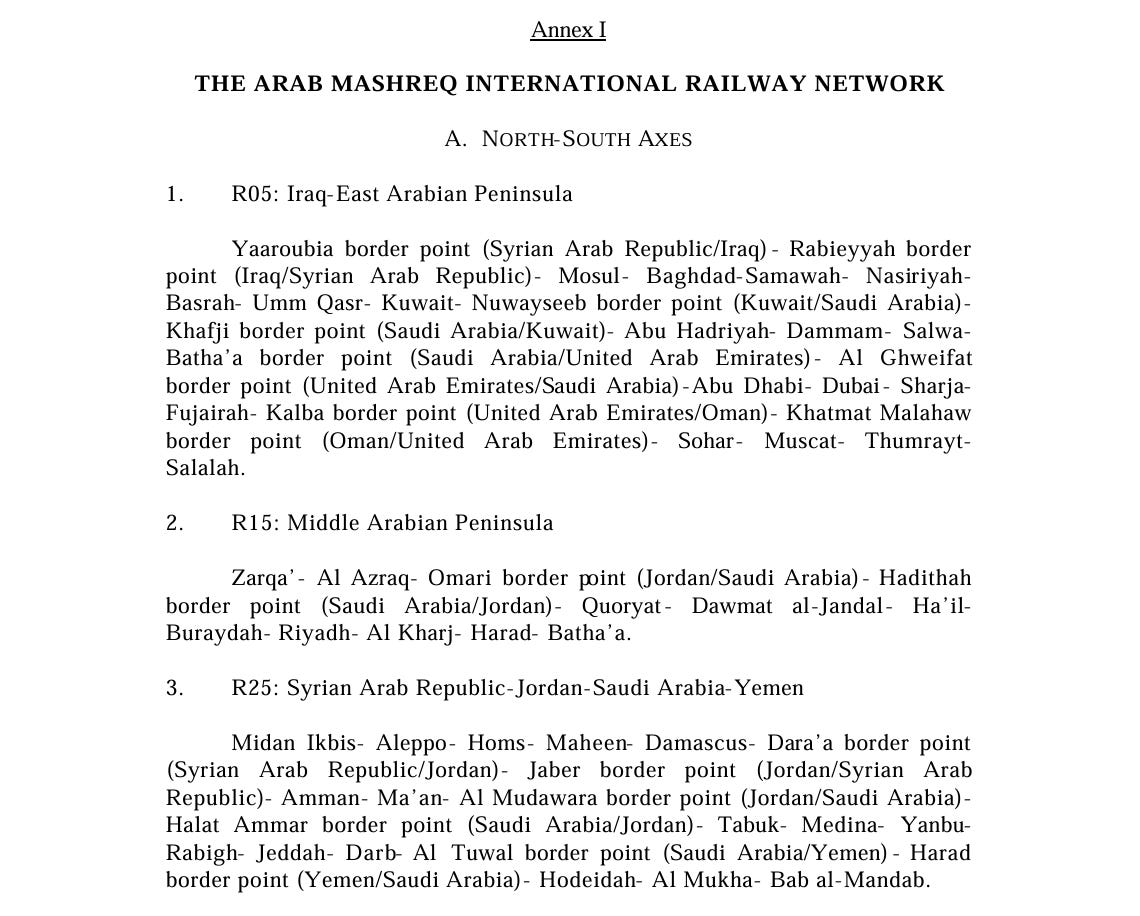

The ESCWA Plan

At the dawn of the 21st century, there had been renewed interest in improving domestic and interstate rail infrastructure. In April 2003, within the framework of the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (ESCWA), the Middle Eastern Arab states drafted an ambitious plan to massively expand inter-state freight railway networks along 16 lines spanning Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Yemen, and the GCC states. The plan aimed to boost economic growth by transforming these states into a new overland route for trade between Europe and East Asia. Sea trade would disembark in Dubai’s Jebel Ali port and be ferried by rail to Syria’s Mediterranean ports of Latakia and Tartus, to embark on its final destination to Europe, and vice versa. This would be considerably faster than traversing the Suez Canal, through which a standard cargo container takes between 28 days (COSCO) and 35 days (Maersk) to get from Shanghai to the Greek port of Piraeus. Through the ESCWA plan, the same container would arrive in Latakia in under 20 days: 17 days by ship to Dubai, then two to three days by rail to Latakia. War and political instability in the Middle East brought an end to the ESCWA plan’s vision: the Iraq invasion in 2003, the Syrian Revolution in 2011, Yemen’s civil war after 2014, and the anti-Qatar blockade between 2017 and 2021 by the UAE, Egypt, and Saudi Arabia, all hindering regional interconnectivity.

Domestic Rail Infrastructure Development

While the full vision of ESCWA has not materialised, since the early 2010s, some of the signatory nations have been pursuing substantial development of their domestic rail infrastructure.

Türkiye was a first mover in the region, with the Republic continuing the work of the Ottoman state and extending the country’s rail network to over 7,600 km, with lines reaching as far as Kars in the Caucasus. This was followed by a decline in rail development for most of the second half of the 20th century, with governments favouring highway expansion. Since the early 2000s, successive AKP governments have refocused on rail, extending the network by 4,000 km, of which 1,200 km delivers High-Speed Rail (HSR) services.

In 2011, the Saudi state-owned Saudi Arabia Railway Company (SAR) began operating the first section of the North-South Railway, built to transport phosphates from mines in the Kingdom’s north to the east coast. The line has since been expanded and currently measures 2,750 km. In 2017, SAR opened a 1250 km passenger railway line from Riyadh to Qurayyat, near the Haditha border crossing with Jordan. In 2018, the Haramain High Speed Rail service was opened, connecting Jeddah, Madina, and Mecca with trains running at speeds up to 300 km/h. This year, construction is set to start on a 1,500 km east-west railway, connecting Jeddah to Dammam and Jubail via Riyadh. Named the Saudi Landbridge, the railway is a joint venture between SAR and a subsidiary of the Chinese state-owned China Railway Construction Corporation.

In 2009, the UAE government established Etihad Rail to build the country’s first railway network. The first stage was completed in 2023, connecting Ghweifat on the Saudi border to Fujairah on the eastern coast near Oman, with a branch to Abu Dhabi’s southern gas fields. This line is currently operational only for freight, although a test journey for the high-speed passenger service was conducted in 2024. Etihad Rail plans to expand the network soon to the currently unconnected northern emirates of Al-Ain, Ajman, Umm Al-Quwain and Ras Al-Khaimah. Etihad Rail is also in the process of connecting its rail network to neighbouring Oman. Once complete, the ‘Hafeet Rail’ network will link the Omani port city of Sohar and the capital, Muscat, with freight and high-speed passenger rail services to and from Abu Dhabi via Al-Ain.

Hafeet Rail would be the first concrete realisation of a long-discussed GCC plan for a pan-GCC railway network running the length of the east coast of the Arabian Peninsula. First mooted in 2009, progress on the Gulf Railway project has been slow, partly due to the deterioration of relations between Qatar and Saudi Arabia and the UAE. However, the recent warming of intra-GCC ties shows movement toward realising the Gulf Railway plan. Notably, in January 2025, Kuwait awarded a contract for the study and detailed design for the first phase of the 111-km Kuwait-Saudi railway to Turkish engineering company Proyapi.

China’s Belt and Road Initiative

There has also been interest in Middle Eastern interconnectivity from the outside. In 2013, the Chinese premier, Xi Jinping, launched China’s plan to transform Eurasian transport, energy and digital logistics: the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). China aims to further their strategic autonomy by reducing dependence on the South China Sea-Indian Ocean-Red Sea trade route, expanding Chinese influence in the Indian Ocean, and countering the US naval presence in all these seas. The overland ‘Belt’ portion of the BRI – comprising the Southern Corridor, connecting China to Europe by rail via Central Asia, Iran, and Türkiye, and the Northern Corridor, connecting China to Europe by rail via Kazakhstan and Russia – seeks to reduce dependence on the Red Sea. Due to the Russo-Ukrainian War, the Northern Corridor currently terminates in Russia. The Southern Corridor does not appear to have progressed past Iran.

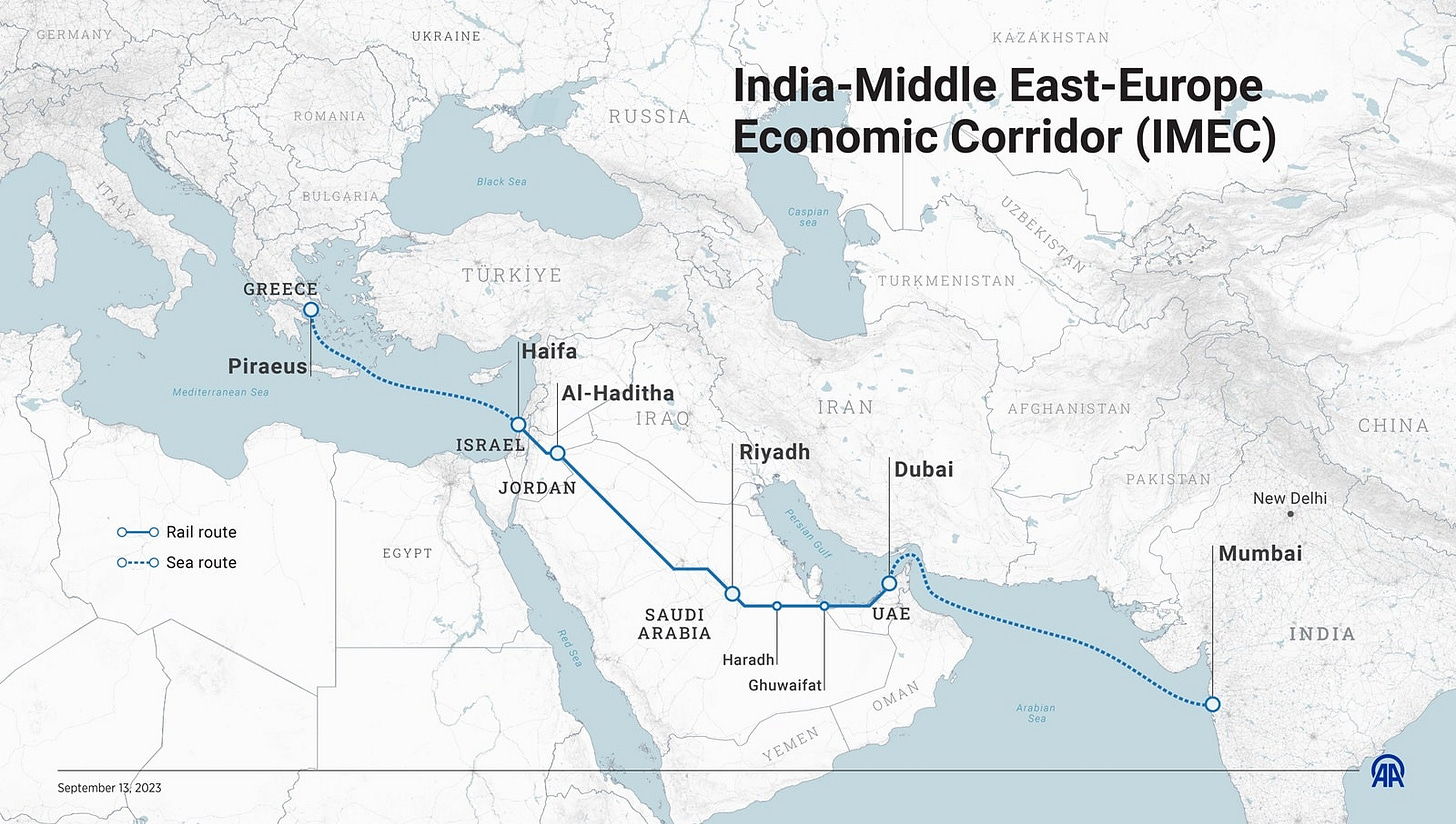

India–Middle East–Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC)

To counter Chinese ambitions, the US began promoting the India–Middle East–Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC). The IMEC aimed to compete with the BRI by opening up a sea and overland corridor through India, Oman, the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Israel, and Cyprus to reach European ports in Greece and Italy. Since the signing of a multilateral MoU in September 2023, progress on the IMEC has stalled owing to Israel’s war in Gaza, which has indefinitely suspended its efforts at regional normalisation, primarily with Saudi Arabia, a pivotal state in the IMEC corridor.

The Iraq Development Road (IDR)

In May 2023, the Turkish president, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, announced an alternative to the IMEC: the Iraq Development Road (IDR), which aimed to connect Türkiye to Basra, on the Persian Gulf, via a redeveloped Iraqi road and rail network. Erdogan’s proposal aimed to counter IMEC’s exclusion of Türkiye, which undermines the country’s long-term strategic objective of being a peerless hub for trans-Eurasian transport and energy links, and did so to the benefit of its main rivals in the East Mediterranean, Greece and Israel.

Syria Changes the Equation

The liberation of Syria from the Assad regime in December 2024, and the swift political progress the new government has made since, could revolutionise Middle Eastern transport logistics and provide a more elegant solution to Indian Ocean-Mediterranean connectivity than either IMEC or IDR. Previously published on Vizier, the emergence of a Sunni Corridor through Türkiye, Syria, Jordan, and the GCC is reshaping the regional balance of power, as well as supply chains. Rail interconnectivity forms a crucial part of this emerging order.

Over the last six months, the Syrian and Turkish ministers of transport have made several detailed public statements outlining plans to restore and upgrade Syria’s domestic rail network, reconnect the Syrian rail network to those of Türkiye and Jordan, and extend this network to the shores the Persian Gulf by way of Jordan, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE. By extension, this would result in linking Istanbul to the Persian Gulf by rail, fulfilling what the Syrian Transport Minister, Yarub Badr, has described as his country’s ambition to become a “regional transportation bridge”. Badr has expressed his cautious ambition that the Middle East Railroad (MER) would not simply comprise freight lines, but would include high-speed passenger services. Speaking to an interviewer from Al-Ikhbariya, Badr said, “We are talking about 250 km/h between Damascus and the Jordanian border.”

The MER would substantially reshape the flow of goods between the Mediterranean and the Indian Ocean. Since the onset of the Russo-Ukrainian War, the only ways to move goods in significant volumes between Europe (and North Africa) and Asia are either via the Suez Canal or the longer sea route around the Cape of Good Hope. A fully integrated, technologically upgraded railway from Türkiye via Syria to the Jebel Ali Port in Dubai would allow goods traversing the Red Sea to arrive on the shores of the Mediterranean, and vice versa, substantially faster than via the Red Sea – a route that has become increasingly costly and dangerous to traverse in recent years due to the reach of Houthi drones and missiles.

The efficiency advantages of this rail corridor over the Red Sea maritime route would result in a considerable volume of goods traffic being diverted away from the Suez Canal toward the Arabian Peninsula. As the BRI progresses, a purely overland route for East-West freight will likely be opened up via Iran and Türkiye, and Türkiye itself may add a second route – the “Middle Corridor” across the Caucasus and Caspian. Nevertheless, no one East-West corridor will ever be sufficient on its own; the Indian Ocean and Mediterranean Sea will always be indispensable global maritime freight highways. If completed, the MER would become the most sought-after means to move that freight from one sea to another.

Beyond the economic benefits that would inevitably accrue to their respective rail logistics sectors from handling this increased flow of international freight, there are a wide variety of more specific economic, geopolitical, and social benefits that could accrue to Türkiye, Syria, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE.

Syria

Syria would experience a massive expansion of its domestic industry. Freight rail is substantially cheaper than road freight. The tonne per mile cost on U.S. Class I Railroads (which are slower than European or Chinese counterparts) is 4 cents/tonne-mile compared to lorries at 18 cents, meaning rail substantially reduces input costs for businesses and the costs of getting goods to market, thereby boosting profitability. Being connected to an international, integrated freight rail network will be a boon for Syrian industries, which already enjoy a ready pool of cheap domestic labour and look set to attract an influx of investment. The sheer volume of goods that could be transported along the MER would also facilitate economies of scale and allow for significant scaling-up in Syrian industries. This not only benefits existing businesses but also incentivises the growth of new businesses and industries attracted by the prospect of tapping into all the advantages of locating along a key international trade artery. This would result in the development of economies of agglomeration, the cost reductions and productivity gains that firms and workers experience from locating near each other, leading to a concentration of economic activity in specific areas.

High-speed passenger rail could play a significant role in boosting Syria’s industry. As recent research has shown, better domestic HSR connectivity results in substantial productivity gains, as reduced travel time leads to increased internal labour mobility, which leads to firm clustering and increased knowledge sharing around HSR hubs, resulting in agglomeration economies. While the benefits to the domestic economy of knowledge sharing are well-known, one recent research paper has found that the benefits of geographic integration and knowledge spillovers accrue primarily to exporters.

A strategically located city such as Aleppo could easily reap the benefits of the new rail corridor. With its manufacturing heritage, large merchant community, and rail connections north to Türkiye, west to Latakia, east to Syria’s agricultural heartland, and south to the ports of the UAE, Aleppo would regain its historic place as an axial commercial city in the region. Notably, the revival of seamless high-volume trade between Aleppo and south-eastern Türkiye, especially Gaziantep, would go a long way to reconnecting Aleppo to its traditional hinterland, from which it was severed with the Treaty of Lausanne in 1923.

Further east, the historically neglected provinces of Raqqa, Deir Al-Zour, and Hasakah would also benefit. In these mostly agricultural regions, instead of sending agricultural products in raw form to the country’s big cities to be processed there, entrepreneurs may be tempted to establish food processing plants on site, near the farms. Of course, the development of industry in Syria’s eastern regions depends on the national rail plan investing substantially in those regions and expanding its rail connections, and not falling into old habits of neglecting the east.

Syria’s two main ports, Tartus and Latakia, stand to benefit enormously from increased trade volume along the MER. Having recently received substantial investment from CMA-CGM and DP World, respectively, these two historically minor East Mediterranean ports could witness substantial growth in the coming years, potentially overshadowing the port of Haifa, or even rivalling Mersin in Türkiye.

Alongside the economic and geopolitical advantages of restoring rail in Syria, the social benefits must also be highlighted. The past 15 years of destructive violence have badly damaged the social fabric of Syria and exacerbated long-standing social tensions and divides, such as urban-rural, big city-small town, and east-west. Reconnecting and expanding Syria’s passenger rail network could play an important role in reuniting the nation.

Crucially, the rail corridor would cement Syria’s place as an indispensable member of the emerging Sunni Corridor, earning the country more influence at the regional level. Moreover, as a key link in a crucial global trade artery, Syria’s importance and influence on the world stage would increase.

Several challenges face Syria’s aspiration to become a regional hub for rail interconnectivity. Firstly, the Syrian government lacks the substantial cash needed to resuscitate Syria’s badly damaged rail network. While Transport Minister Badr cites investor interest (mentioning the Emirati logistics and shipping giant DP World’s explicit interest), securing commitments will be crucial. Secondly, modern freight and passenger railways require a consistent supply of electricity, something Syria currently lacks. While a recent $7 billion Qatari investment in Syria’s power grid is an excellent start, it may be several years before Syria achieves a reliable 24-hour electricity supply. Thirdly, while the security situation in Syria is improving, there is still the ever-present threat of sabotage attacks from Assadist remnants, pro-Iran elements, and small ISIS cells. Criminal gangs stealing rail track, copper wire, and electrical cables are also a problem.

Türkiye

Türkiye is, after Syria, the biggest winner from increased regional rail interconnectivity. The realisation of a railway network from Türkiye to the Persian Gulf via Syria would definitively bury the IMEC project, delivering Erdogan a geopolitical victory over his East Mediterranean rivals, Greece, and Israel. This would also cement Türkiye’s long-term strategic objective to establish Türkiye as the indispensable state in East-West logistics, whether that be for the movement of manufactured goods, commodities and natural resources, energy, or even people (as evidenced by Istanbul International Airport and Turkish Airways).

Türkiye would also be able to deepen its influence in Syria, driven by the simple fact that the country with which Türkiye shares a vast border is hugely important for Türkiye’s economic, political, and security interests. At the same time, this would reduce Türkiye’s reliance on Iran (especially for access to East Asian markets), which, while having stable relations with each other, remain regional rivals. For this reason, Türkiye is pursuing the Middle Corridor, which bypasses Iran via the Caucasus and the Caspian Sea. The MER would act as a complement, opening up new options for Türkiye to access East Asia.

Jordan

Jordan benefits in three ways from the MER. Firstly, it provides direct port access to the Mediterranean. Jordan is currently looking to grow its economy by investing heavily in its phosphate industry. While Jordan can export phosphates via the port of Aqaba on the Red Sea, the ability to access the Syrian Mediterranean coast and the Persian Gulf by rail could supercharge the Jordanian phosphate industry.

Secondly, tourism is a key sector for the Jordanian economy, providing the country with $10.2 billion in foreign exchange last year. A HSR service connecting Jordan to Syria to the north and the wealthy GCC states to the south could provide an important boost to the tourism sector if international HSR services can be provided at a lower cost than plane tickets.

Thirdly, the US, EU, UK and the GCC have propped up the Jordanian economy and maintained the political status quo in the country in the name of regional stability. If Jordan can develop into an important node on the Mediterranean-Indian Ocean rail corridor, it might be able to diversify the sources of its geopolitical importance beyond mere regional stability.

Saudi Arabia and the UAE

For Saudi Arabia, the benefits of the MER are less pronounced than for its northern neighbour, but significant. The principal economic benefits would be an expansion of Saudi mining exports north toward the Mediterranean, as well as a general growth in the country’s transport logistics industry, furthering the Vision 2030 goal of establishing Saudi Arabia as a key global logistics hub. Politically, the main benefit to Saudi Arabia would be its ability to leverage its control over the southern portion of the railway corridor to expand its influence over Syria.

As it is already an international logistics behemoth, the economic benefits to the UAE would be fairly marginal. Nevertheless, an increase in traffic to the UAE’s ports would invariably strengthen the nation’s influence in the Indian Ocean, cementing the UAE as the premier Indian Ocean transhipment hub. In a similar way to Saudi Arabia, the UAE could also leverage its control of the terminus of the MER to cultivate greater influence over Damascus.

Regional integration

While competition for influence over Damascus may flare up, the MER would likely ultimately strengthen interstate relationships. This would not be due to the new economic ties (even hostile states can put aside their differences when it comes to trade), but due to the process of building the rail corridor. The corridor, if it is to be built and run successfully, would require the involved states to work together closely and build joint institutions and shared legal and regulatory frameworks to facilitate the efficient construction and operation of the railway. That process of sustained cooperation and the institutions that would be generated from that process could play an important role in reducing the historic tendency among Arab states to mutual antagonism and political fracturing and, instead, further the cause of regional integration. This will be a significant challenge demanding unprecedented cooperation and robust joint institutions among states with a limited history of large-scale, shared infrastructure projects.

While there would be many gains to be had for the states involved in the MER, at least two states stand to lose out: Egypt and Israel.

Egypt

The Suez Canal has long been an important source of foreign exchange rents for the Egyptian state, generating 15% of the country’s foreign exchange income in 2022/23. The emergence of new, more efficient overland routes for transporting goods between the Mediterranean and East Asia would invariably hurt the Egyptian national coffers. The emergence of this new order in the Middle East also further isolates Egypt. As the most populous Arab state, with a huge military and a long border with Israel, Egypt can never be a marginal player in Middle Eastern politics. Nevertheless, the MER and its potential role in boosting the regional influence of Türkiye and Saudi Arabia and forging closer ties among the Sunni Corridor nations threaten to isolate Egypt on the regional political plane. This process is already underway, as evidenced by Sisi’s recent overtures to Iran, which in October 2024, resulted in the first visit by an Iranian foreign minister to Egyptian soil in 11 years.

Israel

With the MER, IMEC is permanently removed from play. This not only denies the Israeli port of Haifa new traffic from the Gulf, but with a large volume of East-West trade diverted via Syria away from the Suez Canal, the port of Haifa could quickly lose substantial business to Latakia and/or Tartus, either of which could eventually overtake Haifa’s role in transhipment in the East Mediterranean. It also undermines Israel’s attempts to integrate more deeply in the region by strengthening economic ties with the Gulf states. Trade with the UAE is active and flourishing, principally in the realm of software and security and defence technology, but the death of the IMEC would foreclose on the possibility of a booming trade in goods between Israel and the Arabian Peninsula. The MER could also foster greater economic prosperity, political cooperation, and geopolitical integration among the Sunni Arab states and Türkiye. Weakening its regional neighbours economically and politically has been a cornerstone of Israeli national security policy, and any strengthening of the Sunni Corridor is regarded as a security threat by the Israeli state. The proximity of a Damascus-Daraa railway to the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights makes it especially vulnerable to sabotage via proxies (e.g. Suweyda-based Druze militias) or a direct attack.

No Pie in the Sky

Even with substantial challenges, a vision for Middle Eastern Rail is not a pipe dream. First, much of the infrastructure is already there. Saudi Arabia and the UAE have extensive rail networks that are set to grow. Only a relatively short stretch of track is required to connect the Emirati network to the Saudi network. Türkiye possesses an advanced rail network, which is connected to Syria’s, though the Syrian network needs extensive repairs. The main track construction work required is between Damascus and the Saudi-Jordanian border. As of yet, there exists no rail link from Amman or Zarqa to the terminus of Saudi Arabia’s northern railway line, and the Damascus-Amman line is not only damaged but also severely outdated, using Ottoman-era narrow-gauge tracks. Nevertheless, most of the skeleton of the Türkiye to Gulf railway network is in place.

In an interview with Türkiye’s Daily Sabah, Yarub Badr noted that Syria has not withdrawn from regional frameworks and mechanisms that facilitate freight transport and that his ministry is working to reactivate them. Speaking to Al-Ikhbariyya in May, Badr highlighted some of the other practical steps that he and his team are taking to advance Syria’s rail ambitions. The Syrian MoT has recently met with business delegations from Jordan in order to discuss the reopening of the old Hejaz Railway line from Damascus to Amman. Despite its ancient narrow gauge, it is still suitable for transporting freight at moderate speeds and could be repaired very quickly at a cost of only $4 million. Within the MoT, training is high up the agenda. Badr mentioned that MoT staff are currently undertaking a training programme to learn international best practices and develop key software skills to facilitate the ministry’s digitalisation drive.

Alongside improving the MoT’s internal capacities, Badr’s priority at the moment appears to be legal and regulatory reform of the rail sector to create a regulatory framework that is both manageable for the MoT and attractive for investors. To this end, the ministry has enlisted help from the World Bank and the International Finance Corporation who, in Badr’s words, “can offer technical support, support in planning and preparation that can bolster the [state’s] capacity to launch big investment projects in Syria within a competitive, transparent and just environment.”

Yarub Badr’s Turkish counterpart, Abdulkadır Uraloğlu, has also been busily pushing forward with resuscitating Syria’s railway network and its connections to Türkiye. On March 22nd of this year, Uraloğlu announced that Türkiye was preparing an on-site training programme relating to rail (and road) for the Syrian MoT, and that he had assigned Turkish consultants and technical support staff to the Syrian MoT to assist with the preparation of a Transport Master Plan, as well as transport strategy and project planning. Uraloğlu has also sent a team of engineers to assist with repairing and restoring the western portions of Syria’s rail network, which connect to the Turkish rail network via the Al-Rai/Çobanbey and Maydan Akbis/Meydan-ı Ekbez border crossings. The former connects Gaziantep to Damascus via Aleppo, while the latter connects Damascus to Adana via Aleppo.

In Uraloğlu’s words, “At the moment, it is essential to reach Damascus."