How Morocco Built an Automotive Industry from Scratch

Morocco's automotive industry is one of the few development success stories outside of East Asia in the 21st century, but must adapt for a new era of Chinese competition and EVs to survive.

Between 2003 and 2025, Morocco created a domestic automotive industry from scratch, becoming one of the rare industrial success stories outside of East Asia. In doing so, Morocco has joined a league of nations seeking to arbitrage the bifurcation in global supply chains between the United States and China, such as Vietnam, Mexico, Brazil, and Turkiye. Morocco possesses several competitive advantages over these countries: a unique geographical position, infrastructure investment, and industrial policy, all making it a prime contender to take advantage of the U.S.-China rivalry and the European Union’s (EU) uncertainty to become a key node in trade relations between all three of the world’s largest markets.

Morocco’s industrial policy in recent decades has been developed and driven by its King, Muhammad VI (MVI), under whom the Moroccan government has implemented a combination of policies focused on industrial development, attracting foreign direct investment (FDI), utilising exclusive free trade agreements, and investing in infrastructure development, to transform the kingdom into a key automotive manufacturing and export hub in the global supply chain. Bucking regional trends in state capacity, the government has been proactive in not just creating industries but also adapting to change in them, such as with the rise of electric vehicles (EVs), and by ensuring agreements on knowledge and technology transfer in partnership with foreign companies to foster local firm development.

These policies are now paying off. In 2023, Morocco’s automotive exports to the EU reached $14 billion in value on 536,000 cars, comprising 20% of Morocco’s total export value. This places Morocco above China to become the EU's leading automotive exporter in market value, although China remains the EU’s largest in absolute volume, with 782,000 vehicles exported in 2023. In 2024, Morocco achieved another milestone as it displaced South Africa to become the African continent’s largest automotive manufacturer, producing about 614,000 cars, 90% of which were destined for export. The Moroccan government has declared its objective to manufacture one million vehicles by 2030, which would see Morocco jump from the 24th largest automotive manufacturer to the 20th largest automotive manufacturer by volume, in the same league as countries like Russia, Britain, and France, although Morocco has a substantially smaller population.

The Birth of Morocco’s Automotive Industry

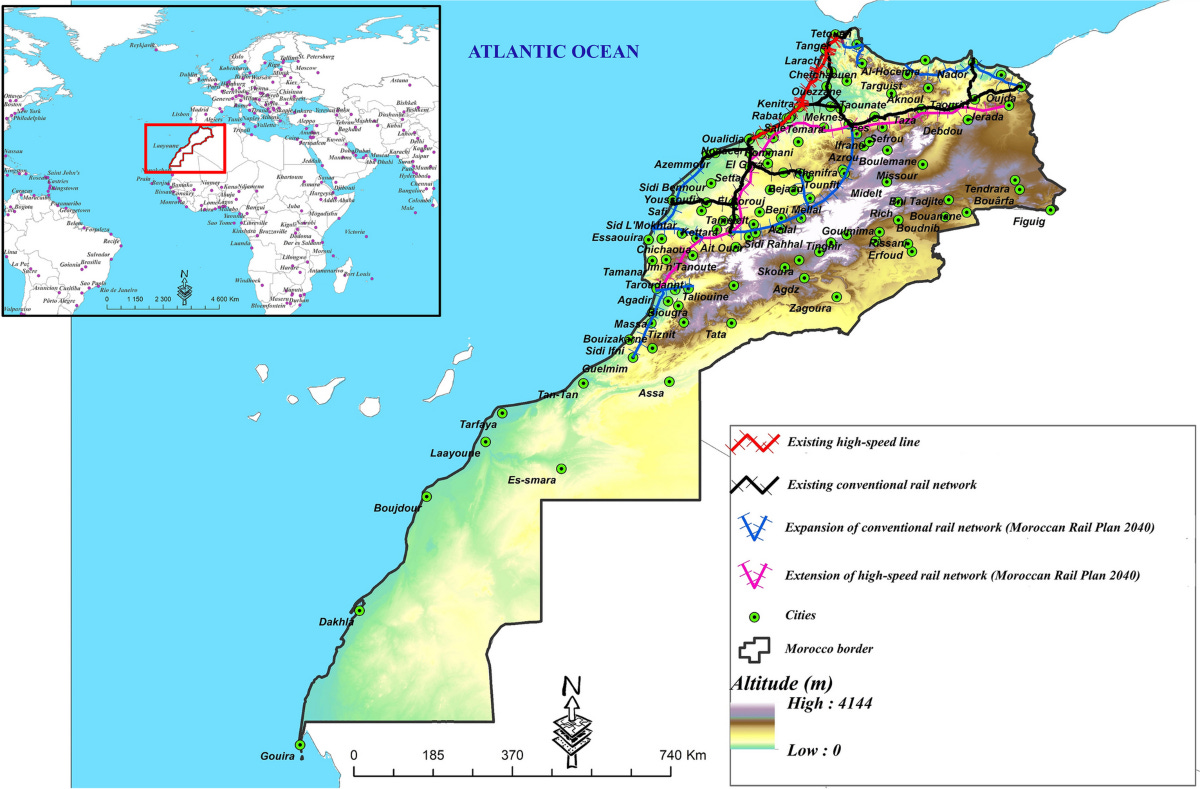

Morocco’s automotive industry, though rooted in post-independence ambitions, only began its journey into a globally competitive industry through strategic reforms and partnerships initiated in the 2000s. Before 2007, the kingdom’s automotive footprint was limited to a single small-scale assembly plant. As of 2025, Morocco hosts three major automotive hubs in Tangier, Kenitra, and Casablanca, supported by a sprawling network of suppliers, positioning the nation as a pivotal node in global automotive supply chains.

The origins of Morocco’s automotive sector trace back to 1959, when the state-owned Société Marocaine de Construction Automobile (Somaca) was established in Casablanca through a partnership with Ford. Initially assembling Fiat models, Somaca later diversified with licenses from Renault (1966), Austin (1969), and Opel (1970), peaking at 30,000 vehicles annually by 1975. Yet this early phase prioritised import substitution over exports, with production aimed almost exclusively at domestic consumption. Limited technology transfer and value-added manufacturing, coupled with macroeconomic challenges including Western Sahara tensions, droughts in the 1980s, and a regional wave of privatisation, stalled progress. While Somaca remained state-owned as a symbol of national pride, Morocco’s market liberalisation exposed its fragile industry to foreign competition, particularly used-car imports, leading to a sharp decline in domestic production.

A turning point emerged in the early 2000s under King MVI's economic modernisation agenda. In 2002, Morocco sold its stake in Somaca to Renault, which acquired Ford’s remaining shares to become the majority owner by 2003. Renault’s then-CEO Carlos Ghosn recognised Morocco’s strategic potential as a low-cost, export-oriented manufacturing base, leveraging its proximity to Europe and existing infrastructure. This vision aligned with the ambitions of Driss Jettou, Morocco’s Prime Minister from 2002 to 2007, whose career in trade and finance ministries under the previous King Hassan II had primed him to pursue industrial transformation. Jettou’s pivotal 2004 U.S. free trade agreement (FTA) and his collaboration with Ghosn laid the groundwork for Morocco’s automotive resurgence.

The Renault partnership accelerated in 2007. Ghosn was exploring Romania as a possible location for expanding Renault manufacturing when he was approached by Jettou while in Paris. Jettou convinced Ghosn to instead pursue this strategy in Morocco, arguing that the Moroccan government would do everything possible to smooth the path and become a true strategic partner to Renault. Jettou and Ghosn finalised plans for a $1.4 billion factory in Tangier within just five months of negotiations. Part of this deal would be the development of the Tanger Med port, which will be discussed later.

Operational by 2012, the Tangier plant became Renault’s largest global site, producing nearly all components for key models like the Dacia Logan locally. This vertically integrated facility exemplified Morocco’s shift from basic assembly to high-value manufacturing, with 90% of output exported. By 2019, Stellantis replicated this model in Kenitra, producing Citroën, Opel, and Fiat vehicles, while Chinese automakers like BYD explored investments to capitalise on Morocco’s trade access to Europe and the U.S. Though BYD ultimately prioritised Hungary and Türkiye, East Asian interest has persisted: in 2024, Morocco’s Minister for Industry, Mohcine Jazouli, toured Japan and South Korea to court investments in automotive and naval sectors, reflecting Morocco’s strategy to diversify industrial partnerships beyond Europe and automotive manufacturing.

Through the ‘special relationship’ between Ghosn and Jettou, and King MVI’s interest in anchoring Moroccan ambitions in global rather than local demand, Morocco has achieved escape velocity from the limitations of its early import-substitution era and is emerging as a linchpin in global supply chains. It now seeks to replicate that relationship into sustainable policy for further industrial endeavours.

Strategic Partners Make Good (Industrial) Policy

The Moroccan government has distinguished itself through a proactive governance model when it comes to its industrial policy, acting as a true strategic partner with foreign businesses, instead of a suspicious, if not hostile, actor. This model involves a willingness to steamroll bureaucratic barriers and streamline processes such as expediting land acquisition, investing in necessary infrastructure, bespoke logistical and workforce training programs, and a general emphasis on accelerating industrial project development. This approach, epitomised by Renault’s rapid establishment of its Tangier plant, contrasts with the bureaucratic inertia plaguing regional peers, where corruption and red tape stifle industrial ambitions.

It is important to note that Morocco’s leeway with large, international businesses is not necessarily replicated for domestic business ventures and investment, or general administration, where bureaucratic obstacles and corruption remain stumbling blocks to growth.

In any case, the political stability afforded by Morocco’s monarchy amplifies the kingdom’s appeal as an investment destination. The country has avoided major upheaval amid regional turbulence and offers investors long-term certainty. Morocco’s monetary policy reinforces this stability: the Moroccan dirham’s peg to a euro-dollar basket minimises currency risk, a critical consideration for export-oriented industries.

This efficiency extends beyond automotive manufacturing. Morocco’s collaboration with French firms SNCF and Alstom on Africa’s first high-speed rail line came after the failure of the French firms’ negotiations with California's government to develop the California High-Speed Rail project. Overcoming land acquisition hurdles and cost overruns that derailed the U.S. project, Morocco successfully operationalised the rail link between Tangier and Casablanca in 2018, with further plans to extend it 800 kilometres south to Agadir. Alstom’s subsequent decision to localise locomotive production in Fez mirrors Renault’s strategy, signalling Morocco’s intent and capacity to compound its automotive success in adjacent heavy industries. Businesses further afield have seen the signal: the South Korean industrial giant, Hyundai, won a $1.54 billion contract in February 2025 to produce double-decker trains in Morocco, with the contract emphasising transfer of technology, further boosting Morocco’s efforts to indigenise prduction.

Complementing infrastructure investments, Morocco has prioritised workforce development through German and Swiss-inspired vocational training programs. Tailored in partnership with automakers, these initiatives aim to ensure a national pipeline of skilled labour, critical for sustaining industrial growth.

Central to Morocco’s strategy are its Special Economic Zones (SEZs), such as Tangier Automotive City and Kenitra Free Zone, which offer tax incentives, world-class infrastructure, and integrated supplier networks. While these zones have driven the automotive sector’s 60% local integration rate, with a target of 80% by 2030, they have also drawn EU scrutiny over perceived unfair subsidies, landing Morocco on the bloc’s financial grey list. This signals the efficacy of Morocco’s SEZ strategy. Undeterred, the government is expanding SEZs near new megaprojects like Nador West Med and Dakhla Atlantic Port, aiming to attract automotive, aerospace, and naval industries. The rise of these SEZs and their strategic role in building Moroccan influence and supply chains through West Africa has been previously discussed on Vizier.

Thanks to the kingdom’s competitive advantages, Renault has been at the forefront of foreign business expansion into Morocco, establishing its Tangier plant as the company's largest production site outside Europe. Today, Renault is Morocco's largest private employer, surpassing even the state-owned, phosphate industry giant OCP. Other major players, such as Stellantis (Peugeot-Citroën), have also established a presence in Morocco, particularly in the Kénitra region. These factories are fully integrated, producing entire vehicles, including high-value components such as engines. Moreover, automotive firms are increasingly investing in local R&D centres to capitalise on Morocco's growing pool of engineering talent. In 2023, Stellantis announced an expansion plan, aiming to produce 500,000 vehicles annually from its Moroccan plants, further solidifying the country's status as a key manufacturing hub. Even South Korean firms are now willing to sign technology

Industrial clustering has created new opportunities. The domestic Moroccan car brand, Neo Motors, now produces vehicles with 90% local components, a feat unimaginable two decades ago. Such achievements reflect Morocco’s strategic geography, just 14 kilometres from the nearest European country, Spain, and straddling Atlantic and Mediterranean trade routes, coupled with aggressive trade diplomacy. While regional blocs like the Arab Maghreb Union languish, with the Maghreb being the least economically integrated region in the world, Morocco has secured bilateral Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) with 50+ countries, granting preferential access to two billion consumers. Morocco further has the unique status as being one of only three nations (with Israel and Jordan) holding simultaneous FTAs with both the EU and U.S., providing a decisive edge over automotive manufacturing rivals like Türkiye and Egypt.

Cars, Ports, and Infrastructure

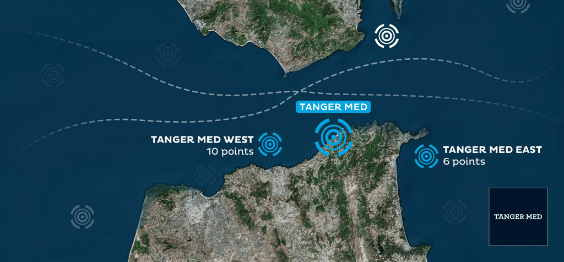

Morocco’s automotive industry has been buoyed by an infrastructure strategy that is transforming the kingdom into a logistical linchpin between Europe, Africa, and the Americas. Central to this transformation is Tanger Med, a port-industrial complex that has transformed Morocco’s formerly isolated geographical location into a new artery for global trade. Tanger Med’s strategic value became evident in 2007, when its proximity to Europe, enabling under 48-hour delivery times to continental markets, helped secure Renault’s landmark investment. Tanger Med offers competitive legal services, high operational efficiency, and cost advantages, outcompeting Spanish ports on the opposite side of the Strait of Gibraltar.

Ranked the world’s 17th-largest container port by capacity in 2024, Tanger Med is the largest port in Africa and the busiest in the Mediterranean, serving as a key node for global shipping routes crossing through the Strait of Gibraltar, and functioning as the engine of Morocco’s export-oriented industrialisation. The Strait sees 13% of global shipping traffic flow through it, rivalling chokepoints like Singapore and Panama. As the winds increasingly blow towards Gibraltar, shipping giant Maersk has seen the opportunity and is investing in a terminal expansion, expanding the port to 15-million TEU capacity, positioning the port to overtake Rotterdam as a top-ten global port.

Tanger Med’s ecosystem, spanning 2,000 hectares of tax-advantaged zones for automotive, aerospace, and tech firms, now generates over half of Morocco’s exports. Its competitiveness stems from seamless logistics, enabled by state-of-the-art automation and PortNet, a blockchain-driven platform streamlining customs and cargo tracking. By colocating suppliers, assembly plants, and export terminals, Morocco achieves supply chain efficiencies unmatched in the Mediterranean, with products shippable within hours of production. In 2024, Tanger Med ranked fourth in the World Container Port Performance Index (CPPI) for 2023. Such integration has drawn parallels to Shenzhen’s 1990s ascent as a global electronics hub.

The port’s strategic foresight extends to sustainability: electrified cranes, solar-powered operations, and biofuel bunkering align with Morocco’s renewable energy ambitions, while expansions like the forthcoming dry dock aim to dominate emerging Global South trade corridors. Already, geopolitical disruptions like the 2024 Red Sea blockade saw Tanger Med’s traffic surge by 23% as ships rerouted through the Strait of Gibraltar.

This model is now being replicated nationwide. Megaprojects like Nador West Med and Dakhla Atlantic Port mirror Tanger Med’s blueprint, combining deepwater ports with Special Economic Zones (SEZs) to anchor industries from automotive to aerospace. Adjacent industrial zones, linked by Africa’s first high-speed rail, Al Boraq, allow manufacturers like Stellantis to move components from factory floors in Kenitra to European showrooms within days. Ports and railways are being connected with air cargo through investment into the expansion of Casablanca’s Mohammed V Airport, and the acquisition of an additional 200 aircraft for the Royal Air Maroc fleet.

EVs, China, and the Future of Morocco’s Automotive Industry

Morocco’s competitive automotive industry faces a new challenge in the form of EVs. While regional competitors like Türkiye (home to EV producer Togg) race to dominate regional markets, Morocco has not been caught by surprise. Morocco’s investment attractiveness is best demonstrated through burgeoning interest from Chinese electric vehicle (EV) manufacturers.

In 2024, Gotion High-Tech, a global leader in EV battery production, announced plans to invest up to $6 billion in Moroccan lithium battery and cathode facilities, which positions Morocco as a critical node in global EV supply chains. Morocco is also receiving further investment from long-time investors and partners. In 2023, Stellantis commenced EV production at its Kenitra plant, becoming the first in the country to do so.

Morocco is also attempting to capitalise on its untapped iron and lithium reserves, both critical to battery production, to reduce reliance on politically volatile sources like the Democratic Republic of Congo. By developing domestic refining capacity, Morocco aims to offer investors vertically integrated supply chains insulated from global mineral shocks.

Parallel to its EV push, Morocco is diversifying into complementary technologies with startups like NamX, which unveiled a hydrogen-powered SUV prototype under royal patronage in 2023. Meanwhile, Neo Motors, now producing 40,000 vehicles annually for corporate fleets, demonstrates the government’s demand-side interventions to nurture local champions. Though Morocco lacks a dedicated EV brand, its deepening expertise in battery components and partnerships with Chinese firms like BTR New Material Group, who are planning a $300 million cathode plant in the kingdom, suggest latent potential for indigenous EV production, possibly through Neo Motors.

Looking ahead, Morocco’s ability to convert mineral wealth and FDI inflows into a cohesive industrial policy will determine the success of its automotive industry. By anchoring itself as a bridge between Chinese battery giants, European automakers, and African markets, the kingdom aims to replicate its combustion-engine success with EVs. However, challenges persist: EV production’s lower mechanical complexity lowers entry barriers for rivals, while Morocco’s nascent hydrogen ecosystem remains years behind European leaders.

Going Where the Wind Blows

Morocco has successfully executed a strategic, patient industrial policy to create an automotive manufacturing industry from scratch. By prioritising structural advantages and sound policy like investment into critical infrastructure, the development of Special Economic Zones (SEZs), political stability, and investor-friendly reforms, the kingdom is transcending its role as a low-cost labour hub to become a high-value export platform. Anchored by megaprojects like Tanger Med, the Mediterranean and Africa’s largest port, and bolstered by partnerships with firms like Renault and Stellantis, Morocco now rivals emerging manufacturing powerhouses such as Vietnam and Mexico in global supply chain integration.

The government hopes that industrial development can address deep-rooted socio-economic challenges. Youth unemployment, exacerbated by an education system ill-suited for industrial needs, is being tackled through vocational reforms like the Cité des Métiers initiative, which aligns skills with market demands by emphasising a technical education. The growth of small and medium enterprises (SMEs), supported by programs such as Banque de Projet, is building a complex ecosystem of suppliers aiming to diversify the economy into aerospace and advanced manufacturing. The country is learning the right lessons from development case studies like the East Asian ‘tiger economies’, demonstrating a curious awareness with regards to state capacity’s importance to successful execution, and creating horizontal and vertical integration within the automotive industry’s value chain, and beyond to other industrial sectors like aerospace.

Morocco’s ambitions face numerous challenges in an increasingly uncertain global economic environment. It must also sustain growth by ascending the value chain through further investment into R&D and domestic EV production, while navigating EU’s use of financial tools and sanctions to stymy Morocco’s economic growth, such as their scrutiny over SEZ subsidies.

If Morocco can continue to act as a preferred strategic partner for international business and leverage its geographic location and unique trade access to 2 billion consumers and mineral resources like lithium, Morocco could evolve from an automotive assembler to an innovation hub in its own right, provided it maintains the agility that propelled its rise. In a multipolar era, Morocco’s automotive industry development is a case study for how to leverage geopolitics, infrastructure, and policy foresight to industrialise on a nation’s own terms.