Syria Weekly Report #3

Weekly Report on Syria, w/b 23/12/24: updates on Syria's political transition, foreign policy, Iran's disinformation campaign, and the road ahead in 2025.

Read Weekly Reports #1 and #2 to catch up with the main developments in Syria in recent weeks.

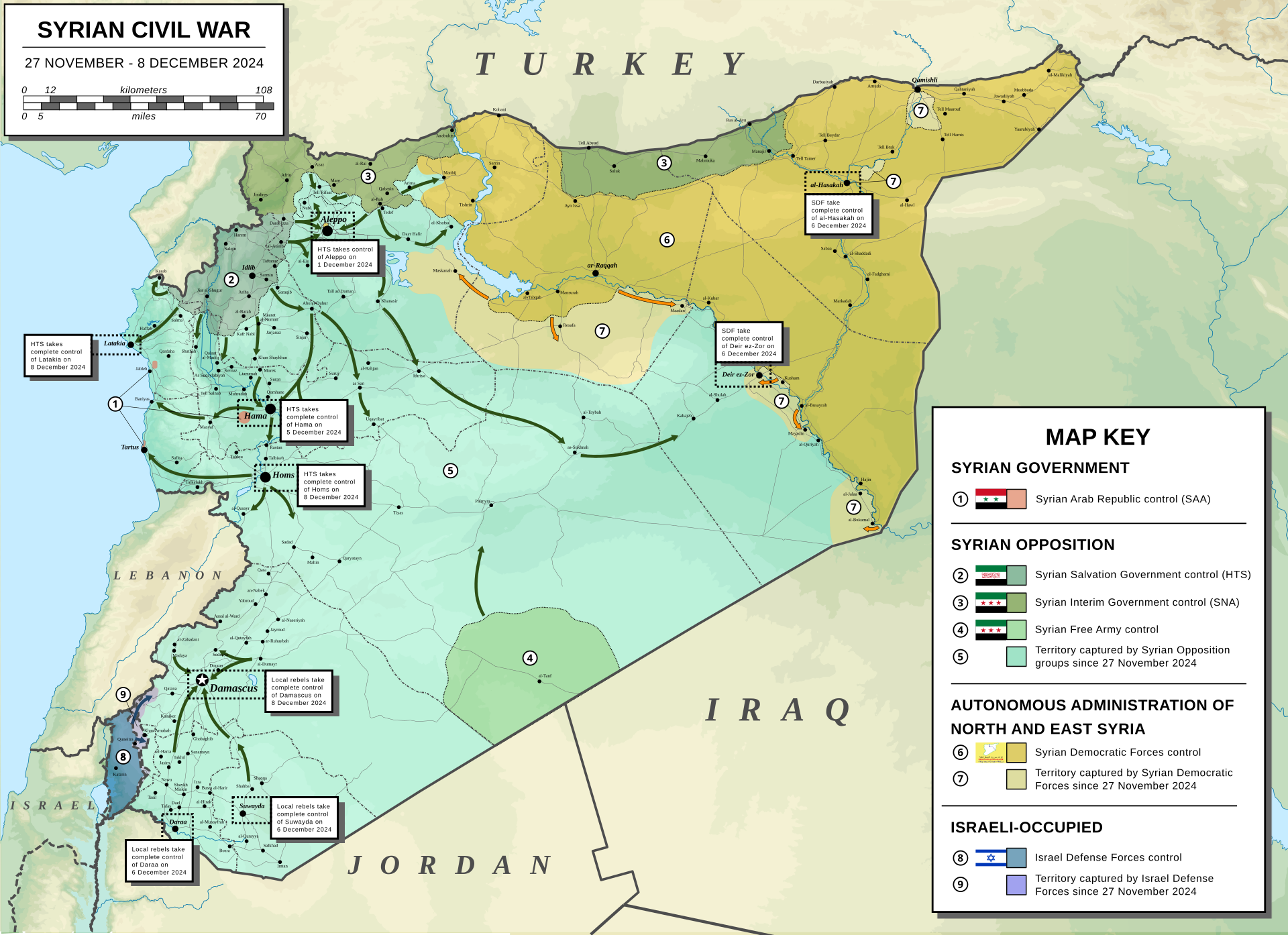

It has been a month since the start of Operation Repelling Aggression led by a coalition of revolutionary forces under HTS that overthrew the Assad regime. There is still a sense of euphoria among Syrians, perhaps a slight suspension of belief, at the unlikelihood and speed with which the Assad regime fell, and that we are entering the new year without the Assad family for the first time in over fifty years.

There is still fear of further unrest, although with every passing week a post-Iraq/Libya scenario becomes less likely as the new ‘administration’ in Syria continues to avoid every mistake made in those scenarios (as discussed in our previous reports).

We now have more colour on the political roadmap ahead for Syria with Ahmad Al-Shara’s interview with Al-Arabiya last night. The interview was interesting for two reasons: one, that it provided more details on what we can expect for Syria in the coming months and years, and two, that it was given to Al-Arabiya, a Saudi state-owned news channel. This is an indication of what Syria’s foreign policy would ideally look like in the near future.

Syria’s Political Roadmap Takes Shape

Al-Shara has given key milestones that gives Syrians and the world a sense of the roadmap ahead. He said that Syrians need a year before real change is felt on the ground, that he expects a new Syrian constitution to be drafted within three years, and for elections to take place in four years.

Al-Shara has made it clear that this process will be by and for Syrians. The UN Resolution 2254 adopted in 2015 to manage a transition of power between the Assad regime and the opposition no longer applies because the regime no longer exists. Additionally, when asked if he considers himself the ‘liberator of Syria’, Al-Shara pushed back and stated that he does not, and that any Syrian who ‘sacrificed for the revolution is a liberator’.

This is indicative of Al-Shara’s recognition of the need for some sort of democratic legitimacy from the people of Syria, and the type of politics that Al-Shara is likely to lead with as Syria’s political landscape takes shape, a sort of ‘populist, technocratic Islamism.’

The National Dialogue

Instead of a UN-led ‘process of transition’, a ‘National Dialogue’ is being held. The purpose of the Dialogue is to gather 1200 Syrians from inside and outside of Syria, representing the spectrum of Syrian society, and have between 70-100 people from every governorate of Syria (of which there are fourteen). A source close to Syria TV suggests that the National Dialogue will be held in coming weeks.

Details around what the Dialogue would discuss and how it would be involved in the decision-making process going forward are still vague, but there are expectations from Syria’s civil society that the Dialogue would at the least have input on Syria’s constitution and the nature and personnel in the post-March interim government. The current ‘interim’ government looks on course to phase out by around March 2025, and the hope is that the Dialogue will help to create a longer term interim government that may govern (with legitimacy) until elections are called.

Al-Shara acknowledged that the current government in its caretaker position is of a ‘single colour’, but that it was necessary to achieve stability in the process of transitioning state authority from the Assad regime. When asked by the interviewer about the status of HTS as an organisation, Al-Shara stated that HTS and other non-state factions would be dissolved at the Dialogue, and that the Syrian state should be the sole military and political authority in Syria.

It is increasingly unlikely that Al-Shara and HTS are unserious about their claims with regards to the primacy of the Syrian state, which is a positive indicator for stability in the country. Al-Shara’s rejection of sectarian quotas featuring in Syria’s future political system is also another positive indicator for stability. Such quotas have ruined neighbouring countries like Iraq and Lebanon, as ministries doled out based on sectarian lines have become stalking horses for sectarian interests at the expense of national interests. Sectarianism and non-state factions have been the main sources of instability and civil war in countries like Iraq, Lebanon, Afghanistan, Libya, Sudan, and others.

The Problems Facing Elections in Syria

A period of three years in which to draft a new constitution for Syria is a conservative estimate. It is likely that the current Syrian constitution will be used with heavy amendments to take into account what Syrians actually desire (as expressed through the National Dialogue), and to alter the political structure of the state.

Drafting a new constitution is the relatively easy part and may not even take three years. In contrast, a soft deadline of four years for elections is very optimistic.

Over half of Syria’s population is internally or externally displaced, many government records for identification have been lost and/or destroyed, and much of the country’s infrastructure is in ruins. It is unclear who is a Syrian citizen, where they are, and whether they are alive or dead. A serious flow of Syrians back to Syria, even from surrounding countries, will not begin until the basic needs (electricity, food, water, and cement for reconstruction) are available, which could take up to a year. Syria is unlikely to reach its pre-war population for several years to come.

As part of the de-Baathification process, there will need to be a full tally of all who partook in the Assad regime’s criminal enterprise to ensure that they cannot participate in future political processes. There is also the presence of foreign fighters among the revolutionary forces who are likely to become naturalised citizens, and the revocation of citizenship issued to various Iraqi, Lebanese, and Iranian elements who came in as part of a broader Iranian-backed scheme for sectarian settlement after 2013.

Then, a full census is needed to tally the actual population and citizenry of the country. Most records, the records that have survived, are on paper, and Syria lacks the technological infrastructure for rapid digitisation. Elections cannot happen without knowing who can vote.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, Syria needs the infrastructure for elections: voting stations, ballot boxes, observers, etc. To create the ‘democratic process’ is also an issue of culture: Syrians need time to rediscover themselves as a society and what it means to partake in political processes, to form groups and parties of interest, and to create a culture of democratic participation. One criticism of the four-year timeline for elections is that this may be an attempt by Al-Shara to consolidate power or even delay elections indefinitely. However, it is likely that if he did announce elections as soon as 2025, he would equally be criticised for making a power grab amid general uncertainty and desire for stability.

For comparison, West Germany held its first elections in 1949, four years after the fall of the Nazi regime. This was with the full participation, support, and observation of the western allied powers. West Germany did not see the same level of displacement as Syria, and as Europe’s industrial powerhouse, had the fundamentals for rapid economic revival. Syria benefits from neither of these things.

Nevertheless, deadlines are important. They set expectations for what Syrians can expect and what they can work towards, expectations that cannot easily be dismissed later. As the roadmap for Syria’s transition becomes more clear in the months to come, the Syrian people will take to the task of rebuilding with gusto.

In the interim period, the two things to look for will be the nature of military-civilian relations and reconstruction efforts (which necessitate sanctions relief).

Al-Shara believes that a Trump administration will see many of the sanctions lifted. Trump’s presidential inauguration is on January 20th 2025, and we will see more colour on both the sanctions and Kurdish issues only once his administration have settled into power.

The relationship between Al-Shara and HTS, the military, and civilian institutions in the state is as of yet unclear. The new interim Minister of Defense, Marhaf Abu Qasra, is tasked with reorganising the Syrian army and folding armed factions outside the state into this army. In the coming months, there is an expectation that all military factions west of the Euphrates are to come under the Ministry of Defense. If this is successfully accomplished, we will get a better picture of military-civilian relations.

These two factors will determine whether or not Syria remains stable long enough to get to elections in four years’ time. Everything else is a footnote.

Syria’s Emerging Foreign Policy Outlook

There were many overtures and words of praise made towards Saudi Arabia in the Al-Arabiya interview, a not-so-subtle indication from Syria’s new administration that it seeks close relations with the kingdom. Al-Shara praised Arabia’s ‘Vision 2030’ plan, said that he misses Riyadh and would like to visit again, and that he was ‘proud of everything that Saudi Arabia had done for Syria.’

Overtures to Saudi Arabia are not just about the hope for aid in economic reconstruction. There is clearly a desire to balance the interests of multiple foreign powers to prevent any single one dominating Syria. In this case, Turkish influence. Additionally, Egypt and the UAE have responded with hostility towards the government in Damascus, and Saudi Arabia is the most powerful Arab state among the trio. Gaining the support of Saudi Arabia will prevent an ‘Arab bloc’ forming against Syria.

Al-Shara also reiterated that Syria seeks balanced relations with Russia and Iran, indicating Syria’s ‘zero problems’ policy towards all powers.

Sectarian Issues in Syria

The Kurdish Issue

When pressed on the future of north-eastern Syria and the SDF, Ahmad Al-Shara rejected the idea of federalism, but also stated that negotiations were ongoing for a peaceful compromise that would bring north-eastern Syria back under the authority of Damascus, and that SDF forces would be integrated into the new Syrian army. No details were given, but there has been a stalemate on the issue over the past week, with no serious fighting.

There are serious, ongoing negotiations between the Damascus government, Turkiye, the USA, and the PKK-led SDF. The continued existence of PKK militants in Syria is a red line for Damascus and Turkiye, and their evacuation of Syria (likely into Northern Iraq) is a prerequisite for a political deal. The Kurdish minority in Syria have many other representatives other than the PKK, such as the Kurdish National Council (KNC). This civilian council, among many other Kurdish opposition groups, were purged by the PKK since 2012. They are now coming back in to serve as civilian representatives.

Their demands revolve around issues of constitutional rights of Kurdish identity and language and the issue of resources in north-eastern Syria. For example, there are heavy references to Arabism in the Syrian constitution which exclude the Kurdish minority and that are likely to be removed, and the ‘Syrian Arab Republic’ will likely become ‘The Republic’ or ‘The State’ of Syria. The Assad regime banned the use of Kurdish in public institutions and went so far as to deny citizenship and passports to many Syrian Kurds. These and other injustices will also need to be rectified if Kurds are to accept the new government in Damascus.

Iran Attempts to Stir Shi’ite Sectarianism

The lack of targeted sectarian violence in Syria since the fall of the Assad regime has undone decades of propaganda made against the Syrian people in general, and the Sunni Arab majority in particular. Apart from reports of reprisals against Assad loyalists after their capture, there has been no instances of mass violence.

However, there have been significant attempts at stirring sectarian disorder over the past week, occurring in the central Syrian provinces of Latakia, Tartus, and Homs as Assad loyalists, embedded within predominantly Alawite communities in these areas, attempted to stir counterrevolutionary riots.

Iranian accounts, including Khamenei’s official Twitter account, have been hard at work in recent weeks to provoke counterrevolutionary sentiment in Syria, even prompting a warning from Syria’s interim foreign minister As’ad Al-Shaybani, to ‘respect Syria’s sovereignty.’

An old video that was previously unseen was ‘leaked’ and showed unidentified individuals in an Alawite shrine in Aleppo. The shrine was on fire and there were bodies, supposedly the shrine’s custodians, on the ground.

Many of the subsequent marches were led by Lebanese individuals affiliated with Hezbollah, infamous Assadist warlords, and Iranian-linked clerics. They stirred many Alawites to take to the streets and chant sectarian statements, including calling for the destruction of mosques, and beheadings. This spurred counterprotests among both Sunnis and Alawites, and religious dignitaries working together to clarify the situation and reduce tensions.

The situation escalated as timing of these protests coincided with Syria’s security forces flooding the central regions and established a security net covering Hama, Homs, Latakia, and Tartus, areas to locate and capture the thousands of Assad loyalists hiding in these provinces.

Hundreds of Assad loyalists fortified positions near the Lebanese-Syrian border in which days of heavy fighting ensued. Many were captured, and their leader, an infamous warlord named Shujaa Al-Ali, was killed. The day prior, Al-Ali had stirred a sectarian mob in Homs where he called for the burning of mosques. He was also involved in the Houla massacre in which over a hundred civilians, most of which were women and children, were butchered with knives. His gang was infamous along the Lebanese border with Homs for kidnapping for ransom, among a litany of other abuses.

There was also an attempted assassination attempt of a Sunni civilian by three Assad loyalists, who transported the Sunni civilian to an Alawite village in the hope that killing him there would provoke sectarian animosity. The loyalists were apprehended by the Alawite villagers before they could accomplish this task and were handed over to security forces, and the Sunni civilian freed and returned to his village.

These events highlight the sectarian instability Iran is still willing to foment in Syria instead of accepting its strategic defeat and revising its foreign policy towards Arab and Sunni countries. Iran has been unable to pivot away from victimhood, sectarianism, and the cultivation of substate militias like those in Iraq, Lebanon, and Syria until recently.

Instead of sowing discord in Syria, Iran may well have provided the sort of “foreign intervention” that has created a greater sense of patriotism in Syria. These events may also prove a boon to the central government as Sunnis and Alawites worked to reduce communal tensions, provide support to the government and security services, and call for an expanded state presence in the region. Additionally, numerous armed factions in both the south and north who are not under HTS proper also pledged their support to help provide security to troubled areas. Early last week, Al-Shara managed to get the main chunk of various revolutionary armed groups to agree to assimilate into the new Ministry of Defense. Today's events may well be used for more consolidation among armed groups into the state.

The swell of patriotism in Syria's public sentiment has possibly never been higher in its history than it is right now. Iran's strategic misstep over the past week, and likely more to come, misunderstands how this patriotism is increasingly uniting the country – against Iran.

Link Dump

Behind the Dismantling of Hezbollah: Decades of Israeli Intelligence ($)

Israeli intelligence has spent decades penetrating Hezbollah’s networks, leading up to the ‘Pager attack’ and Hassan Nasrallah’s assassination.

Secret Assad files show Stasi of Syria put children on trial

Thousands of documents show how the Assad regime constructed a system of spying and fear in Syria, turning Syrians against each other, and imprisoning children as young as 12.

Syria’s new elections and draft constitution: Al-Sharaa outlines timeline

Key points from Ahmad Al-Shara’s interview with Al-Arabiya.

The Remarkable Collapse of Iran’s Powerful Alliances ($)

Iran’s substate empire across the Middle East is collapsing like a house of cards.