Israel Blasts Open Pandora's Box in Syria

How Israel has transformed a local conflict in Suwayda into widespread sectarian violence.

Events in the southern Syrian province of Suwayda over the past week have become the most serious challenge to Syria’s nascent state-building effort since the fall of the Assad regime.

A local tribal conflict in Suwayda between the Druze (an ethno-religious minority group) and the Bedouin (who are predominantly Sunni Arabs) transformed into a full-scale conflict between the Syrian government and Arab tribes against Druze militias and the Israeli air force.

However, this conflict is not at its source a sectarian issue, even as it quickly took on sectarian tones. It is a political conflict between the new government in Damascus seeking to impose its sovereign authority, and the aspirations of the Druze spiritual leader, Hikmat Al-Hijri, and his intransigent refusal to negotiate anything less than complete control of Suwayda’s affairs.

Israel has sought to (successfully) exploit this delicate issue and transform it into an existential crisis that compels both Damascus and Suwayda into a spiralling, zero-sum conflict. But this crisis requires an understanding of the regional context in the years leading up to the fall of the Assad regime, and how Israel has quietly cultivated the ground in south Syria to impose a new political reality — on its own terms, and at the expense of everyone else.

Israel’s Shifting Security Paradigm

The siege of revolutionary-held east Aleppo in late 2016 marked a grim turning point in the fortunes of the revolution. Assad’s forces, backed by Iranian-controlled Shi’a militias, including Lebanon’s Hezbollah, relentlessly bombarded the city into submission, and expelled thousands of fighters and civilians to Idlib and the Turkish border for refugee camps beyond.

Following Aleppo’s fall, the regime shifted focus to recapturing southern Syria, particularly Daraa province and eastern Ghouta. Israel, however, viewed Iran’s deployment of Shi’a militias near the occupied Golan Heights as an existential threat. This prompted Russian mediation, culminating in Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov’s 2018 visit to Tel Aviv, where he personally guaranteed Netanyahu that Shi’a militias would withdraw from southern Syria once Assad secured control.

By mid-2018, Russian-brokered deals had dismantled the revolutionary presence in Daraa through mass expulsions or forced integration of rebels into regime militias. Yet Iran reneged on the agreement: Hezbollah and allied militias entrenched themselves along the Golan border. When Israel protested, Lavrov feigned helplessness, claiming Moscow could not compel Tehran. Iran’s "axis of resistance" now encircled Israel to the north from Lebanon and Syria.

Israel’s strategic opening emerged after the 7 October 2023 attacks by Hamas. Seeking to redeem his security failure, Netanyahu launched aggressive campaigns in Gaza while preparing for wider regional conflict. In coordinated strikes across Syria and Lebanon, Israel decimated Iranian assets, including Revolutionary Guard commanders and Hezbollah leadership, further weakening Assad’s primary sponsors.

Spying an opportunity to escape Iran’s increasingly degraded sphere of influence and desperate for international legitimacy, Assad attempted via Emirati channels to negotiate a Gulf-led process of international normalisation in exchange for the gradual expulsion of Iranian influence from Syria. However, with Russia distracted in Ukraine and Iran’s influence waning, his gambit collapsed.

Exploiting this moment of vulnerability, Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham (HTS) leader Ahmad Al-Shara’ (then known as Abu Muhammad Al-Jolani) launched a lightning offensive from Idlib. In just 11 days, his forces seized Damascus, toppling Assad on 8 December 2024.

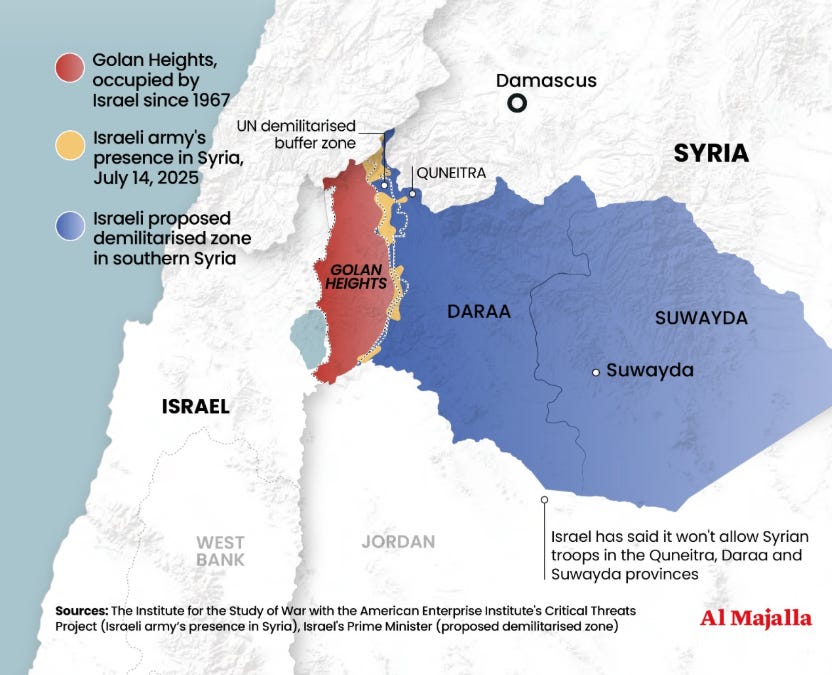

Israel was once again caught off guard in Syria, but saw an opportunity to seize an advantage. One day before the fall of the regime on 8 December 2024, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu convened a security council to put into motion Israel’s strategy for a post-Assad Syria. The result was Operation Arrow of Bashan, the largest aerial campaign in Israeli history. Around 320 locations across Syria were struck, destroying nearly the entire regime’s arsenal: barracks, ports, batteries, arsenals, military airports and equipment; whatever government inherited post-Assad Syria would be left with no military capacity beyond light weaponry.

Israel unilaterally abrogated the 1974 disengagement agreement that had kept peace between Israel and Assad’s Syria for 50 years, moving troops into the demilitarised zone of Quneitra up to Mount Hermon, just 20 kilometres from Damascus. Tel Aviv argued that as the new government in Damascus were unknown, Israel required an additional buffer zone.

Israel was leaving nothing to chance, and began preparing its next card: Hikmat Al-Hijri and the Druze of Suwayda.

The Druze Gambit

Hikmat Al-Hijri is the spiritual leader of the Druze in Syria and the primary antagonist behind the events in Suwayda over the past week.

Al-Hijri had maintained a pro-regime stance throughout the Syrian revolution. This only began to change after 2020, when the Druze in Suwayda started protesting against the regime due to rampant corruption and the deteriorating economic situation, exacerbated by the U.S.’s implementation of the Caesar Sanctions and the regime’s cuts to fuel subsidies. Gradually, the revolutionary three-starred flag replaced the regime’s two-starred flag in Suwayda’s streets.

Initially, Al-Hijri was hesitant to voice serious opposition to the regime itself, let alone lend his support to the protests. The Druze militias in Suwayda were ill-prepared for a direct military confrontation with the Assad regime. However, it was Mowafaq al-Tarif, the spiritual leader of the Druze in Israel, who brokered a relationship between Israel and Al-Hijri, convincing him of the viability of an autonomous Druze province as part of a broader Israeli buffer zone across southern Syria. This zone would remain nominally under Damascus’s authority but effectively under Israeli patronage.

By 2023, Al-Hijri had not only become increasingly vocal against the regime but had also thrown his weight behind the protests in Suwayda. The regime, recognising that Israel was cultivating Suwayda into a protectorate and seeking a pretext to strike regime forces entering the province, largely withdrew, content for the time being to allow Suwayda its autonomy.

After the fall of the Assad regime on 8 December 2024, Al-Hijri established the ‘Suwayda Military Council’ (SMC) to bolster his military capabilities. Modelled after the ‘Syrian Democratic Forces’, which was run by the PKK in northeastern Syria, the SMC’s founding coincided with Netanyahu’s call for the demilitarisation of southern Syria. This suggests that Al-Hijri was preparing the military means to enforce his repeated demands for Druze autonomy over all of Suwayda.

This development had repercussions for the new government in Damascus, which sought to establish ties with older and friendlier Druze militias, such as Layth al-Balaous’s Shaykh al-Karama. Layth’s father, Wahid al-Balaous, had been a soft opponent of the Assad regime until his assassination in 2015 by a car bomb, an operation widely attributed to the regime. Video evidence indicates that Al-Hijri and other prominent Druze spiritual leaders had supported this operation.

Layth intensified his father’s stance, adopting a firmer anti-Assad and anti-Russia position, even as other Druze elders, particularly Al-Hijri, maintained warm relations with the regime. Unlike al-Hijri, Layth was one of the few prominent figures with influence among the younger Druze generation, and he cautiously sought collaboration with the new Damascus government. With his militia, he possessed sufficient clout to negotiate and partner with Damascus in trust-building measures, such as peacekeeping deployments in Druze-populated suburbs of the capital during sectarian tensions.

Today, Layth has largely been abandoned by his own men and exiled from Suwayda due to his soft pro-government stance and opposition to al-Hijri’s monopolisation of decision-making in the region.

Timeline of Events in Suwayda

The Kindling

Tensions between Damascus and the Druze community, primarily the Al-Hijri faction, have persisted for months. Sectarian tensions in Jaramana, a religiously mixed Damascus suburb with a significant Druze presence, between late April and early May 2025 were the first serious test of Damascus-Druze relations. These tensions were smoothed over after Damascus worked with Layth and his militia to enter the suburb and re-establish security, taking over the local police station, arresting agitators to the local peace, and seizing arms.

At the same time, Druze gunmen said to be affiliated with Al-Hijri and the SMC abducted Mustafa Bakour, Damascus’ civilian representative to Suwayda province. Though later released, his kidnapping marked a nadir in negotiations over Suwayda’s relationship with Damascus.

Crucially, Jaramana also established Israel’s willingness to intervene with airstrikes on government targets under the pretext of protecting the Druze. Tel Aviv has repeatedly demanded a "demilitarised zone" in southern Syria, effectively challenging Damascus’ sovereignty by prohibiting government troop deployments near the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights.

Since May, there has been a lull in tensions as figures from the government and the Druze factions and parties sought to reduce tensions, primarily by continuing negotiations. However, after events over the preceding week, it is now unlikely that these negotiations will continue earnestly any time soon.

The immediate trigger to events in Suwayda occurred on 11 July, when Bedouins reportedly extorted a Druze vegetable merchant at a checkpoint on the Damascus-Suwayda highway, beating him and stealing his produce.

In retaliation, Druze gunmen abducted eight Bedouins from Al-Maqous, Suwayda’s predominantly Bedouin neighbourhood, with reports indicating a child was killed during the incident. This ignited a cycle of retaliatory kidnappings, assaults, and killings between Bedouin and Druze militias, prompting tribes across southern Syria to mobilise.

Initially, Damascus refrained from military intervention, opting for mediation as the government was wary of tribal complexities and Israel’s looming threat to exploit any pretext for military action.

By 13 July, however, mediation had failed and large-scale tribal conflict erupted across Suwayda’s countryside and provincial capital, claiming dozens of lives and injuring over a hundred within a single day. Reciprocal shelling and sieges of Druze and Bedouin villages triggered mass displacement, predominantly affecting Bedouin communities.

Following failed local negotiations and escalating violence, Damascus deployed army units and interior ministry police to Suwayda on 14 July to mediate and enforce a ceasefire. This intervention became the catalyst for rapid escalation.

Damascus’ Intervention Goes Awry

To understand why Damascus launched a security operation in Suwayda, we must examine the geopolitical and diplomatic context preceding the decision.

Suwayda poses several problems for Damascus. Firstly, it has become a haven for Assadist officers and other remnants who are fleeing capture, and many of them have been recruited by Al-Hijri into his militia.

Secondly, Suwayda is now the main narcotics smuggling route between Syria and the wider Middle East, a source of regional concern as regional capitals struggle to stem the flow of drugs like captagon flooding the streets.

Thirdly, Suwayda’s push for autonomy comes simultaneously with the PKK’s demands for autonomy across northeastern Syria. If Damascus grants autonomy to one faction, it will likely trigger a cascade of demands until Syria has become a federation of cantons.

Most pressing were Israel’s threats to Damascus over the status of south Syria, and, in particular, Suwayda and the Druze minority — issues that Damascus has felt are its sovereign matters to attend to.

For months, Syrian and Israeli officials had engaged in discreet backchannel talks, facilitated by Turkey, Jordan, the UAE, and the U.S., aimed at achieving détente. After the fall of the Assad regime on 8 December 2024, Israel immediately and unilaterally revoked the 1974 agreement that had established a demilitarised zone between the occupied Golan Heights (annexed by Israel in 1967) and Syria proper. Damascus sought a return to this arrangement, or a similar framework, as it lacks both the desire and capacity for direct conflict with Israel.

Damascus’ decision to intervene in Suwayda likely stemmed from two factors. Firstly, a misreading of diplomatic signals during recent Syrian-Israeli talks in Baku (mediated by Turkey and Azerbaijan). Secondly, overestimating U.S. support for Syrian territorial integrity, particularly after statements by U.S. Envoy Thomas Barrack emphasising the need for a unified Syrian state.

While Washington endorsed Syria’s sovereignty in principle, Damascus read too much into U.S. support and Israeli signals. Bolstered by international rhetoric favouring centralised governance, and under the mistaken belief that Israel would not react, President Ahmad al-Shara and his ministers deemed mid-July the optimal moment to reassert state control over Suwayda and quell the Bedouin-Druze conflict.

On 14 July, Damascus notified Layth al-Balaous, their highest-ranking contact among the Druze factional leaders, of the government’s military deployment into Suwayda to halt Bedouin-Druze conflict. However, as convoys entered the province, Druze militias, likely under Al-Hijri’s command, ambushed a government convoy. Footage circulated by the attackers showed at least 10 soldiers stripped, humiliated, and executed. Eight others were taken hostage, forcibly marched to a Druze village, and killed.

The ambush marked a turning point. Previously positioning itself as a mediator, Damascus now faced open rebellion. Government forces escalated operations, but individual soldiers engaged in reprisals: videos emerged of soldiers shaving Druze men’s moustaches and summarily executing captured militiamen.

The violence reached a nadir at Suwayda’s main hospital, where Syrian troops attempting to evacuate Bedouin civilians were both besieged by Al-Hijri’s militias and subsequently slaughtered. Syrian legal expert Manhal Al-Alou reported that victims were “killed using knives, scalpels, gunfire, strangulation, injections, and by cutting off oxygen supplies.” Misinformation compounded the chaos. Claims that it was government forces that had massacred Druze civilians at the hospital circulated widely, though open-source investigations reveal that this is false.

A local conflict had become a national issue. But this was not the end of the spiral.

Israel Adds Gas to the Fire

Israel’s intervention on 14 July came under the pretext of responding to demands from the country’s Druze community, spearheaded by their spiritual leader Mowafaq Al-Tarif. For days prior, Israeli Druze had been protesting along the border fence in the occupied Golan Heights, some tearing through barriers in desperate attempts to cross into Syria, while Druze soldiers in the Israeli Defence Forces made public declarations of their willingness to deploy into Suwayda.

Beyond its longstanding strategic interest in creating a buffer zone in southern Syria, Israel’s decision to intervene at this precise moment reflected Netanyahu’s precarious domestic position. Increasingly isolated politically, Netanyahu had come to depend on the support of fringe elements like the far-right West Bank settlers Bezalel Smotrich and Itamar Ben-Gvir.

Yet with his coalition balancing on a knife-edge, he also saw an opportunity to court the traditionally Labor -aligned Druze vote, whose historically low voter turnout and fragmented political loyalties made them a potential kingmaker in future elections, with the right incentives. A strong showing of support for Syrian Druze could translate into a reciprocal Druze turnout at election time.

The Israeli campaign began with drone strikes targeting Syrian military and police convoys advancing towards Suwayda city, conducted in apparent coordination with Druze militia operations on the ground. Dozens of government troops were killed in these attacks as they pushed forward, eventually reaching the city centre by 15 July.

That same day saw the announcement of a fragile ceasefire negotiated between Damascus and an assembly of Druze, Christian and civil society leaders in Suwayda – a brief respite shattered within hours when al-Hijri’s faction rejected the agreement and launched simultaneous ambushes against government forces across a dozen locations in the city, timed perfectly with renewed Israeli airstrikes.

American attempts at mediation failed to slow the escalation, and by 16 July, Israeli warplanes were striking central Damascus itself, reducing a portion of the Ministry of Defence to rubble and damaging a section of the Presidential Palace grounds. Though Israel relayed advance warning to Damascus through Turkiye to allow for evacuations, the bombardment killed three civilians and 34 others were injured from shrapnel and blast effects.

In a video address to Israeli Druze that same day, Netanyahu, the architect of the 2018 nation-state law that formalised all non-Jews as second-class citizens (including the Druze), announced, “My brothers, the Druze citizens of Israel, the situation in Suweyda in southwestern Syria is very serious. We are acting to save our Druze brothers and to eliminate the gangs of the regime,” referring to the Syrian government.

Netanyahu was joined in his inflammatory speech by two members of his cabinet, Ben-Gvir and Amichai Chikli, who both called for Syria’s President, Al-Shara, to be assassinated.

Meanwhile, a second ceasefire announcement collapsed immediately when Al-Hijri again refused to comply, despite public condemnations from fellow Druze leaders Yusuf al-Jarbou and Laith al-Balaous, who implicitly accused him of illegitimately monopolising community leadership and endangering Suwayda through his intransigence.

When a third ceasefire backed by U.S. mediation finally mandated the withdrawal of Syrian military forces from the province while allowing interior ministry police to remain, Al-Hijri’s rejection came again, but it mattered little against Damascus’s rapidly diminishing options in the face of Israel’s escalating air campaign.

The sudden Syrian withdrawal created a security vacuum that Al-Hijri’s militias quickly exploited, hunting down the remaining interior ministry officers and unleashing a wave of violence against Bedouin civilians that crossed into outright ethnic cleansing. Graphic footage emerged of entire Bedouin families, women and children among them, gunned down in the open desert, alongside a mass exodus of thousands fleeing towards Daraa province.

The chaos engulfed even humanitarian workers, with the White Helmets’ (civil defence) leader in the province, Hamza Al-Amareen, being kidnapped by militias after he went to Suwayda city to try and escort a UN delegation to safety. His captors, current whereabouts or status (alive or dead) are all unknown.

Full Tribal Mobilisation

The massacres of Bedouin civilians triggered an extraordinary response on 18 July: a full military mobilisation of Arab tribes across Syria. Tribal leaders declared they were "putting aside differences" and "refusing to drink coffee" until Suwayda was restored to state authority. Thousands of armed tribesmen from Deir Ezzor, Aleppo and Daraa began converging on the province, revealing the depth of President al-Shara's previously underestimated tribal networks.

The tribal factor is one of the least understood and least reported on dynamics of Syrian society. If Israel sought to transform a localised conflict in Suwayda into a nationally existential issue for Syria, then Damascus responded by turning Suwayda into a regional concern.

The tribal mobilisation laid bare one of Syria's most opaque but powerful social dynamics. Bound by kinship ties stretching across Iraq, Jordan and the Gulf, these networks carried implicit political weight. While state concerns take precedence over tribal concerns, the latter cannot be ignored at the cultural and familial levels, as they can subtly inform political orientations between states.

As government forces withdrew, tribal militias engaged Druze fighters in chaotic clashes across northern and western Suwayda. The conflict descended into gruesome ritual violence: social media circulated images of Druze militiamen posing with beheaded Bedouin corpses strung from bridges, while tribal forces retaliated with summary executions of prisoners.

Israel's continued airstrikes against tribal convoys failed to stem the tide until 18 July, when international pressure forced a shift. Facing condemnation from mediating powers, including the US, Turkey, Jordan, and Saudi Arabia, Washington's envoy Barrack announced an Israeli-Syrian ceasefire. Having escalated the violence to near-uncontrollable levels, Israel now permitted Damascus to redeploy forces to Suwayda.

Yet Al-Hijri rejected the terms of this ceasefire, marking the fourth ceasefire rejection in five days, and maintained his absolutist stance: no government presence, civilian or military, would be tolerated in what he now considered his personal fiefdom.

By 20 July, tribal forces complied with Damascus' withdrawal orders while government troops re-entered to establish fragile buffer zones between warring factions. These deployments have created precarious humanitarian corridors, though the underlying tensions remain unresolved. The tribal mobilisation had achieved its immediate objective of stabilising the lines of conflict and forcing the Druze militias to facilitate the release of Bedouin civilians held hostage, albeit at great cost.

The Aftermath

On 20 July, Damascus attempted to dispatch a convoy of interior ministry police, civilian ministers including Social Affairs Minister Hind Qabawat and Health Minister Musab al-Ali, alongside vital medical and humanitarian supplies. Al-Hijri again demonstrated his stranglehold over the province, blocking all government-affiliated entry while permitting only international aid organisations access. Faced with Suwayda's deteriorating humanitarian catastrophe, Damascus recalled its convoy to avoid obstructing relief efforts.

The following day, over 1,500 Bedouin civilians, many of whom were women and children held hostage by Druze militias for days as bargaining chips, were finally evacuated from Suwayda to Daraa and Damascus. This marked the culmination of a systematic campaign of ethnic cleansing that had rendered Suwayda city and much of its hinterland entirely devoid of Bedouin inhabitants.

The Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR) documented at least 558 casualties between 13-21 July, including 11 children and 17 women, with 783 wounded. These figures exclude combat fatalities but include extrajudicial executions of captured fighters.

Daraa's health ministry reports over 1,700 casualties across all categories, though the actual total death toll, particularly among government troops, tribal fighters and Druze militiamen, likely far exceeds current estimates.

Al-Hijri's intransigence has defied all mediation attempts, including American pressure, as he continues imposing unilateral terms. His stance has inflamed Syria's Sunni majority and drawn regional Arab condemnation over the transparent ethnic cleansing campaign. With Israeli military backing ensuring his militias' dominance, the stalemate appears unbreakable while Al-Hijri maintains his monopoly on Druze leadership.

Damascus’ Strategic Miscalculations

The crisis in Suwayda represents the most severe strategic, diplomatic, and operational failure for Damascus since the fall of the Assad regime. At its core lies a triad of strategic miscalculations: an overestimation of their military cohesion, a flawed intelligence assessment of Druze politics, and a dangerous misreading of international signals.

Firstly, seven months after the regime’s collapse, the reconstituted Syrian army remains a patchwork of poorly trained, undisciplined factions. The Suwayda operation laid bare these deficiencies, with viral videos showing soldiers forcibly shaving Druze men’s moustaches and making sectarian statements. Though some perpetrators were arrested, the damage was irreversible. These actions validated Al-Hijri’s narrative of Damascus as a "sectarian jihadist" force, eroding any remaining Druze trust. The subsequent massacres of government troops and the chaotic withdrawal, which enabled Druze militias to ethnically cleanse Bedouin communities, have sparked nationwide outrage, particularly among Syria’s Sunni majority.

Secondly, Damascus’ strategy hinged on exploiting Druze factionalism, notably through Layth al-Balaous, leader of the ostensibly pro-government Rijal al-Karama. Yet when violence erupted, al-Balaous was abandoned by his own fighters, some of his closest friends and advisors were killed, and his organisation defected to Al-Hijri. Other former intermediaries, like Suleyman Abdul Baqi of Tajamu’ Ahrar Jabal and Abu Yahya Hassan Al-Atrash of the Kata’ib Sultan Pasha Al-Atrash, also joined with Al-Hijri. This divide-and-rule tactic to isolate Al-Hijri failed; instead, rival Druze factions quickly closed ranks, leaving Damascus without a single credible partner in Suwayda.

Thirdly, rhetorical Western support for Syrian unity, particularly from US Envoy Thomas Barrack, lulled Al-Shara and his government into a false sense of security, believing that there would be US support for the operation in Suwayda. The misreading of Israeli demands over the demilitarisation of southern Syria compounded this crisis. The Suwayda offensive played directly into Israel’s hands, cornering Damascus between impossible options: abandon Suwayda and show weakness, or pursue sunken costs and face a devastating war by Israel, at which point Israel could formally establish its buffer zone in south Syria, a plan it had been cultivating since 2018 and had been sought with greater urgency after the 10/7 attacks.

Israel Against Regional Stability

Far from unintended collateral damage, Israel has executed a deliberate strategy to destabilise Syria. Israel transformed a local dispute into a national crisis, then intervened under the guise of protecting minorities.

The international reaction to these events has been blanket condemnation of Israel’s actions. In a joint statement by Saudi Arabia, Jordan, the UAE, Bahrain, Turkiye, Iraq, Oman, Qatar, Kuwait, Lebanon, and Egypt, they affirmed “Syria’s security, unity, stability and sovereignty” and rejected “all foreign interference in its (Syria's) affairs.”

In a UN Security Council session on 17th July, every member state condemned Israel’s actions in Syria, including the US, in a rare show of disapproval against Israel. The US State Department also released a statement saying that it (i.e. the Trump administration) did not support Israel’s airstrikes on Syria. There is growing concern in the White House over Netanyahu’s willingness to act unilaterally, even against US interests. A senior US official reportedly told an Israeli counterpart, "You can’t embark on a new war every few days. We’re trying to lower the flames and reduce the number of wars and fronts, and you are doing the opposite." However, it is unclear how or if the US will impose red lines on Israel, as it has thus far shown an unwillingness to do so.

To attribute this crisis to Israeli miscalculation would be dangerously naive. No nation possesses more intimate knowledge of Syria’s sectarian fault lines than Israel, which has spent decades studying and manipulating them. It would be extraordinary if Israel did not know or seek to unleash a spiral of sectarian violence far beyond the capacity of Damascus to manage it.

For regional powers like Saudi Arabia and Turkiye, there is a growing consensus on the ‘Israel Problem,’ as Tel Aviv has proven unwilling to become a partner for stability in the region. In fact, doing the opposite at every given opportunity. From the Gaza genocide, to the pre-emptive bombing of Iran’s nuclear plants and decapitating much of its leadership, to the attacks in southern Syria; Israel’s unilateral regional strategy, enabled by a blank cheque from the U.S., is setting the stage for a long-term realignment of regional interests.

Like the two-state solution, a dead horse beaten repeatedly for decades as Israel expanded settlements and tightened the noose on Palestinians in the West Bank, it has become increasingly clear that Israel is no longer interested in the Abraham Accords as a unified diplomatic opening with the Arab and Muslim world. Israel continues to pursue piecemeal normalisation where it can get it, but has eliminated any possibility of a two-state solution – a red line for Saudi Arabia’s terms of normalisation.

Turkiye has avoided confrontation with Israel and instead sought to engage diplomatically, but has found itself outmanoeuvred in Syria. Ankara’s proposed defence pact with Damascus remains stalled, caught between Arab suspicions of Turkish ambitions in the Arab world, and Israel’s demonstrated willingness to sabotage any arrangement that might strengthen Syrian sovereignty or bolster Turkiye’s regional reach.

As early as January, we reported on Damascus’ pursuit of peace with Israel. It seems that Israel is more interested in keeping Syria on its knees as part of its post-October 2023 strategic pivot towards “regional chaos for peace at home.” Nor does Damascus have much room for manoeuvre. Domestic sentiment has shifted from a desire for an end to war so that Syria can rebuild to public outrage against Israel. If Al-Sharaa were to pursue some sort of normalisation deal for peace with Israel, it may now be political suicide.

The message to regional powers seems to be increasingly that American guarantees have become worthless, and Israel will punish any attempt to build alternatives to its dominance. In this zero-sum calculus, Israel’s intervention in Syria serves multiple purposes: to keep Damascus weak, and to make of them an example to others against challenging Israel’s regional primacy.

Sentiments on the Sunni Street

There is intense anger against Damascus from its supporters among the Sunni Arab majority. Tribal mobilisation has partially delegitimised the state to some degree, demonstrating how non-state actors fill the vacuum when state action fails. There is a rising clamour of existential dread among many Sunnis, fearing that the state cannot protect them from a return to the Assad era of brutality and that they may have to mobilise on their own terms.

This poses a fundamental problem to Damascus’ state-and-nation-building project in Syria. If Damascus loses legitimacy in the eyes of the international community or minority sects, this threatens Syria’s redevelopment. However, if the Sunni majority sees Damascus as illegitimate, an Iraq-style collapse is on the horizon.

It is in the interests of Damascus that Sunni majoritarianism is not stoked to a maximal degree, because that fire will overthrow even the government itself in pursuit of safety. But this issue cannot be controlled if foreign actors turn minority sects into fronts for division, and further provoke the extreme, existential trauma of the Sunni majority.

This is precisely what Israel has gambled on: to delegitimise Syria’s nascent state-building process in everyone’s eyes, Sunni, Druze and otherwise, and encourage escalating tribal and sectarian division. Al-Hijri and the Druze militias have played a key role in catalysing a potential path to national fragmentation, and has forced the entire Druze community into a bargain with Israel that not only alienates them from their neighbours in Syria and the wider region, but it is not clear that Israel is even willing to commit to protecting the Druze from the repercussions of its involvement.

What Al-Hijri has done to the Druze image goes beyond Syria. Arab social media, particularly in Jordan and the Arab Gulf (especially Saudi Arabia), has been in uproar over the total Bedouin displacement in Suwayda. On social media platforms like X, Saudi citizens were discussing how to fire Druze employees and boycott Druze businesses.

What Comes Next

The international reaction, particularly Western policymaking circles, may now reconsider the lifting of sanctions on Syria. But economic misery and a lack of sustained redevelopment owing to crippling sanctions largely remaining in effect is precisely one of the key driving forces of tensions in the country, and the inability of the government to develop the bureaucratic capacity to provide solutions to various problems.

If Brussels and Washington walk back their decision to lift sanctions on Syria in light of events in Suwayda, they will embolden foreign actors like Israel and Iran to instigate further chaos in the country, primarily by catalysing further sectarian tensions to permanently cripple Damascus and all but ensure the permanent fragmentation of Syria.

Accountability for the events in Suwayda is necessary and must be universal. After seven months, there have been no public trials for Assad regime members who have been accused of crimes against the Syrian people. Now, Damascus’ problem of transitional justice and accountability is compounded by the need for arrests and trials against those who committed violations in Suwayda as the smallest, first step towards building any semblance of trust in Syrian society.

However, the most glaring issue remains the presence of Al-Hijri. The presence of Assadist officers in his military council, his emboldened position through Israeli support, and his absolute intransigence with Damascus, all suggest that a détente along current lines is the best that can be hoped for in south Syria.

It is unclear how the situation in Suwayda can be resolved until moderate Druze factions from within its well-established civil society are willing to bypass their religious leadership, i.e. Al-Hijri, and begin a process with Damascus under international mediation to restore civilian order, guarantee the rights of both Bedouin and Druze inhabitants in Suwayda, and contend with the rampant smuggling networks and Assadists who have sought haven in the province since 8 December.

Anything else is just kicking the can down the road – and leaking gasoline all the way.