Syria's State Takes Shape

Syria's new national security council, constitution, government, and fatwa council reveal the country's emerging landscape of power and policy priorities over the next five years

Syria’s State Takes Shape

Events over the past month have further defined the emerging landscape of power in Syria. We also have a better idea of the Syrian government’s policy priorities over the 5-year transitional period: reconstruction of Syria’s infrastructure and economy, enforcing Syria’s territorial integrity and security, and ensuring transitional justice.

The four key events in March to be covered in this article:

On March 12th, a national security council (NSC) was formed.

On March 14th, Syria’s transitional constitution was formally promulgated.

On March 28th, the formation of the supreme fatwa council and the appointment of Usama Al-Rifai as Grand Mufti further consolidated the ‘Sunni Big Tent’, the social and religious bedrock for the new Syrian state.

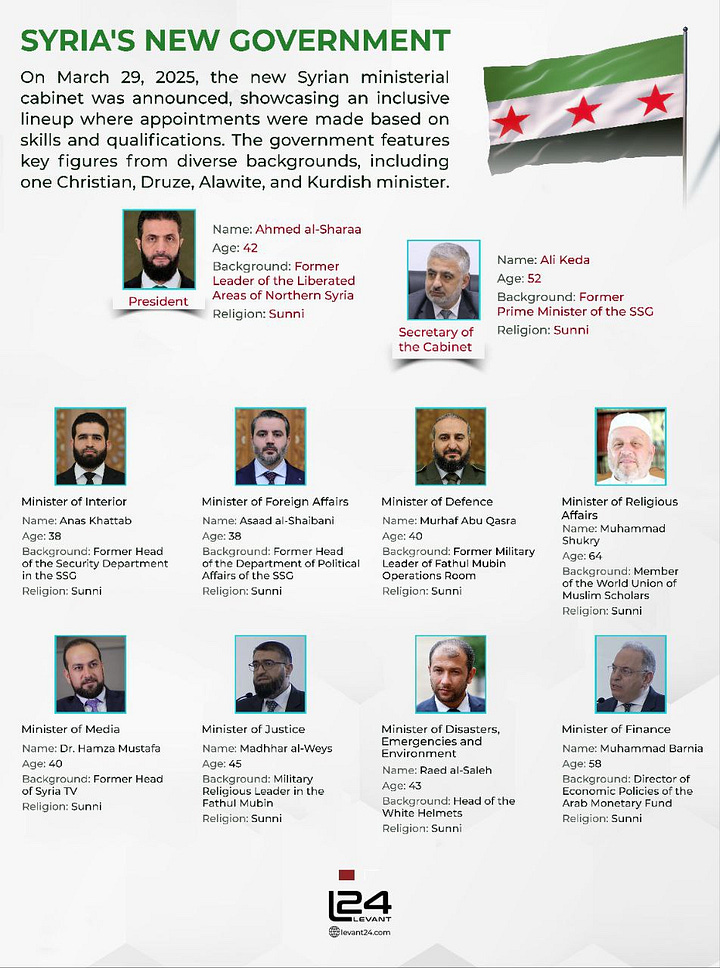

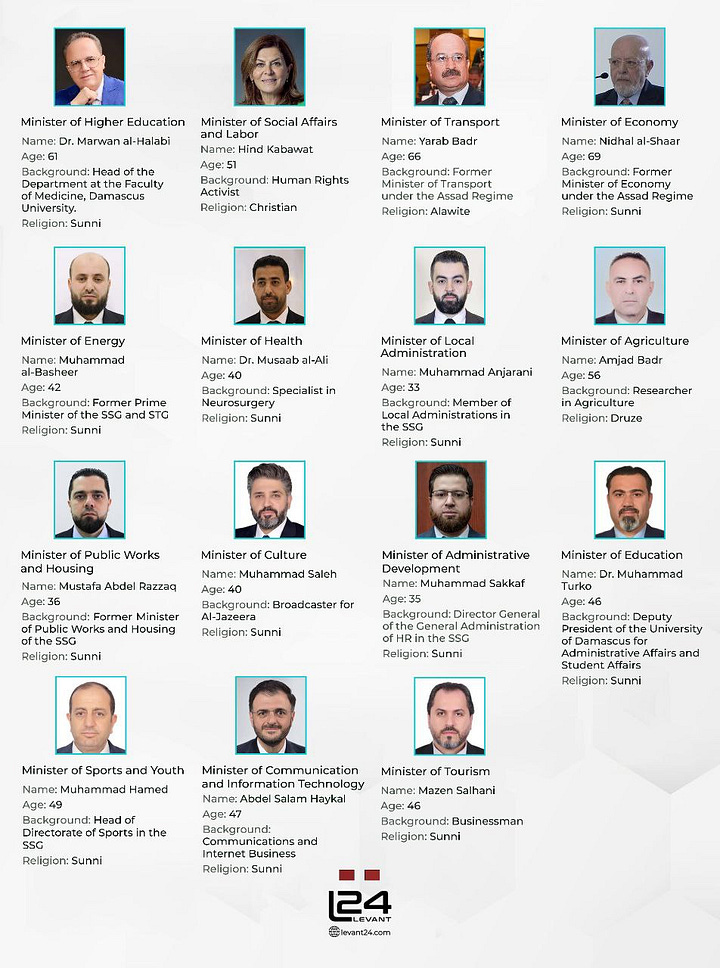

On March 29th, Syria’s transitional government was appointed by President Ahmad Al-Shara, formally succeeding the interim government in power since December 8th 2024.

The council of 5 have mostly retained their prominent ministerial positions (with one change) and also run the NSC. President Ahmad Al-Shara has been granted wide-ranging powers under the transitional constitution with an expected bias towards executive power.

The council’s concentration of power in key positions has also come with a significant broadening of representation in the transitional government, which was formed based on technocratic competency to ensure an appropriate skillset for rebuilding the country. The cabinet includes ministers from every ethnic and religious group in Syria (except the Ismaili community), with many being known civil society figures with extensive experience in their relevant fields, as well as educational backgrounds in Germany, France, the UK, and the USA—among other countries.

This two-track approach, with ‘owned power’ held by an ideologically-aligned ‘deep state’ and a technocratic government thus depending on ‘borrowed power’, is unlikely to be clearly defined by the transitional constitution. Instead, this approach will depend more on the relationships, interests, and political dynamics that emerge in the months and years ahead as a new political culture takes root in Syria, and perhaps be more accurately represented in a future, permanent constitution.

These developments represent the most hopeful post-war/revolution transition of any Arab state in recent decades. The government has tried to strike a balance between political stability and broadening political participation to prevent an outcome like in Libya, Iraq, or Egypt. The formation of the transitional government is as close to an ideal outcome as is possible under the prevailing conditions.

If Syria is to prove exceptional in the long run, the government should continue to undertake a cautious transition that focuses on reconstruction to get its economy moving, transitional justice to heal the wounds of Syrian society, and the assiduous cultivation of a real (i.e. domestic) and healthy political culture as a prerequisite to a mature democratic system.

The National Security Council

On March 12th, Al-Shara announced the formation of a National Security Council to ‘coordinate and manage security and political policies’. Additionally, According to Article 41 of the transitional constitution, through approval by the NSC, the President can declare general mobilisation, war, and a state of emergency.

The NSC is headed by the President (Al-Shara) and includes the following members:

Minister of Foreign Affairs

Minister of Defence

Director of General Intelligence

Minister of Interior

Advisory seats, appointed by the President based on competence and experience

A specialised technical seat, appointed by the President, to follow up on technical and scientific affairs

The formation of the NSC came just days after Assadist insurgents launched an attempted coup on the Syrian coast on March 6th, in which over a thousand people (Syrian soldiers, insurgents, and civilians) were killed. The initial government response to these events was marked by chaos. The government could not control the numerous armed factions and individuals outside of the chain of command of the interior or defence ministries, who flooded the Syrian coast. Many committed looting, revenge killings, and other abuses against civilians in the chaos, and the government had to suspend operations against insurgents to bring the situation under control.

You can read more about these events in the report below:

While planning for the formation of the NSC was already well underway, these events likely accelerated its formal announcement. The NSC’s objective is to coordinate the various security-related state institutions to respond more effectively to Syria’s security challenges. That the key members of the NSC are of ‘one colour’ (i.e. the council of 5) is to Syria’s benefit at this yet-nascent stage in state-building, as rapid security coordination is necessary to respond to the challenges that continue to plague Syria, both internally and externally.

Syria’s borders with Iraq and Lebanon remain a porous conduit for Iranian-sponsored terrorist activities in Syria. Israel has launched a ground invasion in south Syria and bombs Syria weekly in ongoing efforts to destabilise the country. The PKK-run “SDF” continue to occupy northeast Syria. Then there are the internal challenges: Assadist insurgents continue to launch sporadic attacks on security forces, and gangs conduct weapons and drug trafficking, kidnappings, and sabotage of key infrastructure like electricity plants across the country.

The NSC is a crucial step in institutionalising Syria’s security strategy and coordination between state institutions to avoid similar scenes of chaos and tragedy as occurred during the Assadist insurgency on the coast.

The Transitional Constitution

On March 14th, Syria’s transitional constitution was formally promulgated by Al-Shara. The constitution is largely based on the 1950 constitution with minor modifications. It was the last constitution formed by a democratic government before Syria’s ill-fated union with Egypt between 1958 and 1961 when a new constitution was promulgated. In 1963, the Ba’athists launched a coup, promulgating yet another constitution, and also commencing Syria’s long misery.

The constitution has been criticised for being the product of a hasty ‘national dialogue’ process that lasted a few short weeks, and was then drafted over 10 days by a specialist team of 7 legal experts with vague guidelines from the national dialogue. However, considering the need to bring order to Syria, establish a legitimate legislative body, and gain more international legitimacy to gain sanctions relief, this was always going to be a haphazard affair. What is important is that the transitional constitution establishes powers that provide a sufficient framework for work to get done, and that it is not permanent so that a more appropriate (and permanent) constitution can be promulgated when Syria’s situation becomes stable.

At a high level, the constitution enshrines many elements of international law, freedom of speech and opinion, the protection of women’s rights, and freedom of belief. There is a broad separation of powers between the executive, legislative, and judicial branches of government—though, as ever, the devil is in the details, of which there are few.

Under Article 24, the president retains wide-ranging powers, including the appointment of 1/3rd of the upcoming legislative assembly that will form Syria’s ‘transitional parliament’. The remaining 2/3rds of the legislative body will be appointed by an ‘independent committee’, although this committee will be appointed by the president, ensuring that their legislative agenda will be implemented. Article 30 lays out the responsibilities of the assembly, which largely includes the standard powers of a legislative body. Under Article 25, no member of the assembly may be removed without 2/3rds of the assembly voting for their removal, which is a check on presidential power over the assembly.

This and other articles suggest that the assembly seems constitutionally designed to function akin to a shura council which can advise but not legislate in opposition to the president. However, we should learn lessons from other post-conflict countries without widespread buy-in and a mature political culture, like post-Bashir Sudan or post-Ben Ali Tunisia, where various political parties and factions failed to agree on either the nature of the constitution or saw permanent parliamentary gridlock. Syria’s legislative body will not be paralysed and can focus on getting the country on the road to recovery.

The constitution reveals more about the policy priorities of the government in the transitional period. There is a heavy emphasis throughout the document on unity, territorial integrity, and the indivisible nature of the Syrian state, mentioned in the preamble and at least six articles. This is aimed at internal and external efforts to push for “federalism” in Syria, or even outright separatism (calls for separatism or foreign intervention are criminalised). The preamble also emphasises the need for Syria to confront the past, hinting at what is hoped for to be a stronger emphasis on transitional justice soon. The lack of transitional justice has been one of the most consistent criticisms of the prior interim government and Al-Shara himself.

There has been a clear decision to leave radical change for later and avoid the mistakes made in countries like Sudan, Tunisia and Egypt, where political actors immediately polarised their respective societies by placing constitutional matters at the heart of the political transition. This constitution is unlikely to be the “end-state” constitution for Syria, but it offers a starting point that can be developed after the culmination of the 5-year transitional period when the government has promised elections will take place. This future constitution would then likely more closely resemble the political culture that is developed between 2025 and 2030.

The Transitional Government

On Saturday 29th March, two days before the conclusion of Ramadan with Eid Al-Fitr, Al-Shara formally appointed a transitional government to replace the interim government that has been in power since December 8th 2024. As per the transitional constitution, the government will govern for the 5-year transitional period until formal elections can take place.

In The Council of Five Build a Deep State, we looked at the contours of power emerging in Syria under the previous interim government appointed in December 2024:

With the soft deadline for Syria’s current government looming in March, we should expect to see significant changes with ‘outsiders’ (i.e. non-HTS) appointed to positions in the government cabinet for the first time, and perhaps many more positions opened up lower down the rung. I expect that economic decision-making will be one of the fastest areas to open up to outsiders. While the council will retain control over critical ministries such as defence, intelligence, interior, and foreign affairs, the early appointment of Maysaa Sabreen, Syria’s first female central bank governor, signals a calculated openness to outside expertise on matters pertaining to the economy, particularly based on Syria’s immediate need for economic reconstruction and the council’s lack of expertise in that capacity.

As predicted, the council of 5 remain largely in place, with one change: Anas Khattab has replaced Ali Keda as interior minister, and Keda is now Secretary-General of the government. It is unclear who the intelligence minister is, or if the council plans to fold intelligence into another ministerial portfolio (i.e. the interior ministry).

Another change is the elevation of long-time Al-Shara ally and a top jurist in HTS, Mazhar Al-Ways, as justice minister. The importance of the judiciary to Syria’s state-building efforts, the increasingly urgent need for transitional justice, and Al-Ways’ long-term relationship with Al-Shara make him a ‘+1’ to the council of 5, thus strengthening the council.

However, participation in the rest of the government has been significantly broadened, with nearly the entire interim government being replaced except for the 5+1 council, and the interim government Prime Minister Muhammad Al-Bashir who is now energy minister.

This cabinet has been broadly welcomed both by Syrian society and international powers, owing to the strength of their backgrounds and their (relative) diversity. You can find a full breakdown of the new cabinet’s positions and backgrounds here, including individual speeches and translated excerpts made by all ministers during the appointment ceremony on March 29th.

The cabinet includes individuals from across Syria’s demographic and geographic base:

9 ministers who have some prior involvement with HTS, and the other 14 do not

3 ministers who are former Assad regime government officials (before 2011)

11 ministers who have prior involvement in civil society initiatives

1 Christian (social affairs & labour minister), 1 Alawite (transportation minister), 1 Kurd (education minister), 1 half-Turkmen half-Arab (information minister), and 1 Druze (agriculture minister)

18 are Sunni Arabs, and 20 are Sunni when including the Kurdish and half-Turkmen ministers

While the government has formally disavowed a quota system, this cabinet practices a soft quota in all but name. The current agriculture minister, who is Druze, was appointed after another Druze individual had rejected the position, suggesting that certain seats have been softly designated for certain communities. The only ethnic/religious community not represented in the cabinet are the Ismailis, who have nonetheless developed remarkably strong ties with the government in just a few months.

Considering Syria’s delicate situation, making the government of 'one colour’ would create attack vectors against its legitimacy, regardless of the degree of meritocracy involved in appointments. Even so, it is evident from their academic and professional backgrounds that every minister who has been appointed has a strong CV, making this an appropriate balance between a skilled government cabinet to navigate Syria’s transitional stage, and building trust with Syria’s various communities through representation.

In any case, this cabinet’s (unenviable) policy priorities over the next 5 years are to provide transitional justice, rebuild Syria’s infrastructure and economy, and establish security throughout the country. Only by succeeding in these priorities can Syria hope to develop a mature political system by the end of the transitional period.

The Sunni Big Tent

On March 28th, Al-Shara established the 15-member supreme fatwa council consisting of a broad range of prominent Muslim scholars from across Syria’s religious establishment. Crucially, Usama Al-Rifai has been appointed as Syria’s Grand Mufti which also means he heads the fatwa council.

In previous reports, we looked at the developing relationship between Syria’s returning ulema, and Al-Shara and his government:

The general return of Syria’s scholars presents Ahmad Al-Shara with opportunities and challenges. Al-Shara is now Syria’s premier statesman, and if he wants to maintain that role, he has to build a broad political tent. Syria is roughly 80% Sunni (with Arabs forming 70% and the Kurds forming another 10%). Most of Syria’s Sunni community is deeply religious and the authority of the ulema class, for many, is above even the authority of the state. An alliance between Syria’s scholarly establishment and Al-Shara’s state-building efforts would unify the majority of the country under one legitimate authority, making a counter-revolution from within Syria’s Sunni majority extremely unlikely.

The fatwa council is responsible for issuing fatawa (i.e. religious edicts) on public issues, appointing muftis, and providing guidance on other public and civil matters. It is not yet clear how the fatwa council will influence legislation, although Article 3 of the transitional constitution places fiqh (Islamic jurisprudence) as the main source of legislation, which suggests at the very least an indirect relationship.

Al-Rifai has historically been in opposition to Al-Shara and the now disbanded HTS, not least because they follow the Salafi school of thought, whereas Al-Rifai comes from the Sufi-Ash’ari school that has historically dominated Syria’s Sunni mainstream. In any case, Al-Rifai’s appointment is part of a long-running rapprochement between Al-Shara and HTS and Syria’s (pro-revolution) scholarly establishment. This rapprochement has gone as far as the fatwa council’s makeup featuring a majority from the Damascene scholarly elite which largely share the same background as Al-Rifai, with HTS’-aligned Salafi scholars forming a minority on the council.

Al-Shara hopes to balance Syria’s various Sunni currents and form part of a ‘Sunni big tent’ that can stabilise Syrian society, as he declared during the ceremony that established the fatwa council and appointed Al-Rifai as Grand Mufti:

“Syria has always been a scientific, cultural, and religious base, from which goodness was issued to the general public of our nation, until Syria fell into the hands of the corrupt gang; when evil appeared, calamity spread, and efforts were made to demolish Syria, pillar by pillar… It is now incumbent upon us to restore to Syria what the fallen regime had destroyed, the most important of which is to restore the position of Grand Mufti of Syria. This position is now held by one of the finest scholars of Syria, the virtuous Sheikh Usama al-Rifai… The Fatwa Council will seek to regulate moderate religious discourse that combines authenticity and modernity, while preserving identity, resolving disputes that lead to division, and closing the door to evil and all disagreement.”

This is a positive and stabilising step towards the institutionalisation of Syria’s diverse Sunni currents, but much work remains ahead in harmonising Salafi and non-Salafi currents on the ground in Syrian society. Al-Shara is strengthening his hand against the more radical elements who are ‘to the right’ within or outside of HTS (when it existed), and sees this rapprochement as well as Al-Shara’s general overtures to Syrian society as a “dilution” if not betrayal of their cause.

The Road Ahead

Syria’s cautious state-building efforts belie the scale of achievement over the past four months since the fall of the Assad regime, something well understood by the public. A public-opinion poll conducted on behalf of The Economist interviewed 1500 Syrians from across Syrian society. 70% of Syrians interviewed are optimistic about Syria’s future, 80% feel freer than they did under the Assad regime, and a similar percentage views Al-Shara in a positive light. In short: Syrians are giving both Al-Shara and his government a chance at rebuilding the country.

The delay in radical decisions or catering to unrealistic demands to immediately reform Syria’s state and society, in favour of prioritising policy on reconstruction, security, territorial integrity, and transitional justice is the correct decision. This also gives Syrian society the time it needs to rebuild before throwing itself into complicated and contested questions like the constitutional design of the country. This mistake is what undid the democratic transition of countries like Tunisia, or mired them in sectarian dysfunction and violence like in Lebanon and Iraq.

The balance between sovereignty and legitimacy is found in the tension between the 5+1 council’s concentration of power and the government it has appointed, consciously designed to balance technocratic competence with diverse representation, and in no small part to acquire international legitimacy. It seems to have worked, as both regional and western governments have welcomed the appointment of the new government.

Perhaps the least discussed but potentially most destabilising ‘sectarian’ issue in Syria is likely to be inter-Sunni tensions. Through the supreme fatwa council and Al-Rifai’s appointment as Grand Mufti, Syria’s Sunni community is now largely uniting under a ‘big tent’ that harmonises popular and rivalrous religious currents before they cause real social tensions, and creates a true political centre.

This religious legitimacy will also contribute to the legislative base for the transitional government’s agenda, who now have a mandate to carry out their work. The next step is to form a legislative assembly. As per the constitution, Al-Shara will appoint a ‘people’s assembly’ to carry out the work of legislation under the government. Once the assembly is formed, we should see significant progress being made in governance reforms.

As for Syria’s security, the formation of the NSC should see more efficient and professional responses to Syria’s enormous and varied security challenges, hopefully avoiding the tragedies and chaos that occurred in early March on the coast.

Much of this has been accomplished with the benefit of hindsight. Learning from the mistakes of the Arab Spring, but also the failures of the political models of Syria’s neighbours, have been important lessons on what not to do when trying to build a new state. Unfortunately, there is no playbook for what Syria should be doing to build a state. Figuring that out will depend on both the tenacity of Syria’s people and the continuation of competent leadership. So far, we have seen ample demonstration of both, perhaps enough to hope against hope.

Fire. I would like more analysis/breakdown of the Fatwa council at some point!