Kais Saied’s Developmentalist Gamble

Tunisia's president embarks on a radical development programme to reform the country's political economy

On July 25th 2021, 10 years after the overthrow of President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali in the Arab Spring, protests once more broke out across Tunisia. Another wave of COVID-19 was reaching its peak as the country struggled with a high mortality rate and a healthcare system on its knees. The protests demanded the dissolution of Parliament and the resignation of the ruling party, Ennahdha.

That evening, President Kais Saied, elected in 2019, appeared on television in a surprise national address. Invoking Article 80 of the 2014 Constitution—which granted him exceptional powers in the event of a threat to the country’s security and sovereignty—he announced the dissolution of the government, the freezing of Parliament, the lifting of MPs’ immunity, and the initiation of legal proceedings against many of them. Soon after, the army blocked access to Parliament, and Saied launched a massive anti-corruption campaign targeting nearly 500 businessmen.

Tunisia’s return to autocratic rule was met with scenes of jubilation across the country. While the Tunisian opposition and foreign political analysts feared a return to dictatorship and the reversal of the Tunisian revolution’s gains, a segment of the population saw in Saied a restoration of the revolution’s promise of stability and prosperity that had failed to materialise over the previous decade.

Saied’s obscure background, his monotone formal Arabic, lack of a political party, and small media presence to communicate his ideas and interests, have all contributed to a sense of enigma surrounding him. What does Saied want to achieve?

Tunisia’s latest autocrat has quietly embarked on a developmentalist campaign to reform Tunisia’s political economy through a new model of ‘State Capitalism with Tunisian Characteristics’, aimed at rationalising the Tunisian state, breaking Tunisia out of its IMF debt and addiction to neoliberal reforms, and stabilising the country.

The rise of ‘Saiedism’ must be contextualised in the country’s long history of autocratic rule, the economic failure of IMF reforms, and the political failure of the Arab Spring to materialise a stable, democratic, and prosperous Tunisia.

Seeking Rents: Between State & Patrimonialism

Tunisia has historically enjoyed the image of being the IMF’s model student—a prosperous, stable, and modern(ising) country, exceptional in the region and Arab world. Behind this facade, the country was a laboratory for neoliberalism that ultimately failed to deliver on economic development, let alone a transition to democracy.

After Tunisia’s independence in 1956 and the abolition of the Beylik regime in 1957, Habib Bourguiba sidelined the old beldi elite of Tunis—landowners and wealthy families composed of religious jurists, merchant families, and administrators of Turkish and Mamluk origin—and replaced them with a new ruling class composed of the petite bourgeoisie of the Tunisian Sahel (predominantly from the cities of Monastir, Sousse, and Mahdia).

This new elite, French-speaking, secular, and affiliated with the Neo-Destour party, consolidated power by centralising the state under their control. State centralisation came with state dominance of the economy, which necessitated breaking the economic dominance of the former beldi elite. To accomplish this, Bourguiba collectivised land, shut down the prestigious Zaytuna University, and established state-owned enterprises to monopolise the economy.

The failure of Bourguiba’s collectivist policies in the 1960s led to partial liberalisation in the 1970s, allowing a new bourgeoisie from the upper ranks of the Bourguibist administration to emerge and gradually form marital alliances with the once-wealthy beldi families and form new economic dynasties.1 This began Tunisia’s descent into patrimonialism as the economy came to be dominated by private dynastic family ownership.2

The collectivisation model of the 1960s and partial liberalisation-turned-patrimonialism in the 1970s failed to produce sustainable economic growth. In 1986, with Tunisia still under Bourguiba’s rule, the economy experienced a severe recession, prompting Bourguiba to accept an IMF intervention. The IMF imposed a structural adjustment plan (SAP) in exchange for providing financing to the Tunisian government, intending to make Tunisia a ‘more competitive economy’ through a series of neoliberal reforms: a 20% devaluation of the dinar, privatisation of public enterprises (which largely favoured the circle of power close to Bourguiba), export liberalisation, relaxation of labour laws, a reduction of the budget deficit from 5% to 1%, reduction of import tariffs, and cuts to gas and electricity subsidies which were critical for Tunisia’s poor.3

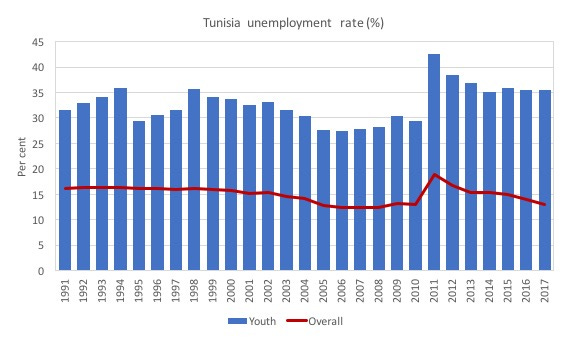

The IMF’s SAP for Tunisia would lead to an average annual growth rate of 5% GDP. However, unemployment remained high–15% overall and up to 40% among the youth–and deep regional inequalities remained, with most economic development occurring in the northeast regions around the capital, Tunis, leaving the central and southern regions in protracted states of undevelopment owing to lack of investment.4

In 1987, amid the economic crisis and increasing confrontations between the secular Tunisian elite and rising Islamist political sentiment, President Bourguiba was overthrown in a coup by his right-hand man, Zin El Abidine Ben Ali. The former was declared “mentally incapacitated” owing to a series of erratic decisions which many in Tunisia (and foreign powers like Italy) feared could provoke civil strife similar to that brewing in Algeria.

Ben Ali assumed the presidency and promised reforms, but he would instead intensify Tunisia’s patrimonial economy. By the 2000s, the Trabelsi clan, from which hailed Ben Ali’s wife, Leila Ben Ali, had sidelined the old Bourguiba elite and monopolised economic rents to the tune of 21% of all private sector profits flowing back to the Trabelsis and Ben Alis.5

The economy became increasingly closed off to protect their interests, while foreign investment was concentrated in low-value-added sectors like textiles, electrical wiring, and olive oil production, all of which offered few jobs. These companies were attracted to Tunisia’s educated workforce, low wages, and favourable tax conditions, but more than half of Tunisia’s workforce were on a precarious form of contract called ‘subtracting’, earning 25 to 40% less than permanent workers. Subcontracting has been called a “form of disguised slavery.”6

With the Trabelsi clan’s monopolisation of the economy and focus on rent extraction activities, smuggling and the informal economy exploded, accounting for 30% of GDP by 2010.7 This system relied on an authoritarian police state practising mass surveillance and violently repressing opposition.

Matters came to a head on December 17th 2010 when Mohamed Bouazizi, a 26-year-old street vendor in the city of Sidi Bouzid had his merchandise confiscated by municipal agents, one of whom (a woman) reportedly slapped him. His pleas for the return of his merchandise fell on deaf ears. Bouazizi then self-immolated in protest, later dying from his injuries. This triggered a wave of protests, empowered by social media platforms like Facebook and Twitter, which first engulfed the marginalised central regions before spreading throughout the country. The slogans echoed: “Bread and water, but no Ben Ali”, “Work, freedom, dignity”, and “The people want the end of the regime.”

Bouazizi’s self-immolation was a symbolic ‘lighting of the spark’ that would see what would later be labelled the ‘Arab Spring’ spreading to nearly all Arab countries. Tunisia was the first domino to fall: despite fierce repression, the uprising reached the capital, Tunis. On January 14th 2011, Ben Ali and his clan fled the country to Saudi Arabia.

The Rise & Fall of Tunisia’s Democratic Experiment

The fall of Ben Ali’s regime sent Tunisia into a period of political limbo in which a little-known constitutional law professor, Kais Saied, first began making the rounds in the media and on university campuses. He distinguished himself through his speeches in classical Arabic in which he demanded respect for the popular will, the dismantling of the old regime and resignation of the interim government (composed of ministers from the Rassemblement Constitutionnel Démocratique, or Democratic Constitutional Rally—Ben Ali’s party), the election of a constituent assembly, and a “decentralised democracy”.

The first election for Tunisia’s constituent assembly was won by the ‘Islamist’ political party Ennahdha with 37% of the popular vote. Led by long-term opposition figure and democratic activist Rached Ghannouchi, Ennahdha was the only truly organised party at the time and sought to ease Tunisia’s transition into democracy by avoiding the monopolisation of decision-making power or imposing an ideological agenda on Tunisia. So, Ennahdha formed and led Tunisia’s first post-revolution government in a coalition with two centre-left parties.

Ghannouchi’s pragmatism was insufficient. The victory of Ennahdha, considered a Muslim Brotherhood-lite party, shocked the secular-liberal segment of Tunisian society predominantly composed of elites. In response, Beji Caid Essebsi, an old guard figure of the Bourguiba regime and head of the outgoing interim government (which governed after Ben Ali had fled the country), founded a secular opposition party called Nidaa Tounes in 2012 with the media and financial support of Nabil Karoui, a media tycoon nicknamed the “Tunisian Berlusconi”. This movement would bring together Tunisia’s secular-liberals in opposition to Ennahdha, polarising political life around questions of identity and the role of religion in state and society.

As Tunisian society became mired in these debates, economic instability and security worsened. Two left-wing MPs who had opposed Ennahdha were assassinated in 2013, sending accusations flying across the political spectrum about complicity.8 At the same time, a bill was proposed to parliament to audit the external debt under Ben Ali. The goal was to classify the external debts contracted by Ben Ali’s regime between 1987 and 2011 as odious debt, which would have allowed for its cancellation or conversion into investment. The initiative was supported by 100 members of the European Parliament, Norway, and the Belgian Senate. Eva Joly, the president of the European Parliament’s development committee, estimated that Tunisia’s debt exceeds 20 billion euros and that its burden is unbearable for the economy, suggesting that the country should follow Iceland's example and refuse to pay those debts, and convert it into aid or investment.9

Ennahda refused to adopt this bill because, according to its Secretary of State for Finance Slim Besbes, there was no urgency to repay the debt, and Tunisia would be able to do so in any case. Ennahdha seemed to believe that by doing so they would earn greater legitimacy with international institutions, primarily by appealing to the global neoliberal consensus.10

The previous year had seen another Islamist party in Egypt, led by then-President Muhammad Morsi, overthrown in a military coup. Under regional pressure and facing an internal political stalemate in Tunisia, Ennahdha sought to assuage concerns held against the party and handed power in January 2014 to a technocratic government led by Mehdi Jomaa, a senior executive at the French multinational energy company Total’s subsidiary in Tunisia. Jomaa would implement further neoliberal reforms not unlike those that came after the 1986 recession, including an IMF loan of $1.2 billion which resulted in the devaluation of the dinar, a reduction of corporate tax from 30% to 25%, and an increase of 10% in income tax.11

In late 2014, new presidential and legislative elections were held, and Beji Caid Essebsi won the presidency, with his party obtaining a majority. Against popular expectations, Essebsi allied with Ennahda to form a coalition, even though his movement had positioned itself as a bulwark against political Islam. These coalitions were aimed at stabilising Tunisia’s deeply polarised political landscape, but would fail to resolve these issues as the Tunisian economy continued to flounder, a crisis compounded by neoliberal reforms.

Matters were made worse as two terrorist attacks targeting tourists in 2015 deepened Tunisia’s economic woes, and the tourism sector—representing 14% of GDP and a major source of foreign currency—collapsed.12 Between 2016 and 2019, a government led by Prime Minister Youssef Chahed implemented more austerity measures and contracted a new loan of $2.9 billion from the IMF.13 However, this failed to relieve Tunisia’s economic problems like slow growth (1.8% on average), a bloated administration, and public debt rising from 59% to 70% of GDP. The IMF’s reform programme proved difficult to implement due to social conflict and political pressure from the UGTT, the general labour union with deep economic influence in Tunisia.

In further neoliberal reforms, the Tunisian Central Bank became an autonomous and independent institution in 2016, imposing a monetary policy with interest rates decoupled to the economic environment and government policy, worsening the trade deficit and increasing the rentier nature of the banking sector.

With a polarised society, stagnant economy, and ever-weakening state, Tunisia’s democratic experiment began to falter.

Kais Saied’s Rise to Power

Tunisians grew weary of economic stagnation and political stalemate. In July 2019, President Essebsi died in office and early presidential and legislative elections were called. Kais Saied was among the first candidates to declare his campaign and ran as an independent, claiming that “his party is the people.” He refused all campaign financing and was the only candidate not to solicit campaign subsidies. He announced that he would make no promises but ‘would respond to the aspirations of the revolution’.

Opposed to political parties, the parliamentary system, and endemic corruption, Saied defended his project of “decentralised democracy” in which local councils would elect regional councils, which would then designate a National People’s Assembly. This reform aimed to give more power to marginalised regions and to reinforce the state’s social and sovereign role.

Against all expectations, Saied won the first round, and in the second round, he faced Nabil Karoui, again winning decisively with 72% of the votes.

Saied now faced a problem: he did not have a party in the legislature. Ennahdha was the largest party, followed by Nabil Karoui’s Qalb Tounes party. Ennahdha initially tried to form a coalition which was rejected by parliament. In response, Saied appointed Elyes Fakhfakh to form a government, which tried to include Ennahdha but exclude Qalb Tounes, something that Ennahdha refused. Under threat of dissolution, a new cabinet was eventually formed without Qalb Tounes, and Ennahdha granted its confidence.

Six months later, Fakhfakh tried to dismiss the Ennahdha ministers in government, but they passed a no-confidence motion and forced Fakhfakh’s resignation. Saied then appointed Hichem Mechichi, a senior civil servant and minister of the Interior under Fakhfakh. However, Saied refused the swearing-in of some ministers chosen by Mechichi on suspicion of corruption or ties to the Ben Ali regime.

In this chaos, Ghannouchi—then Parliamentary President—was accused of overstepping his role by engaging in ‘track II diplomacy.’ He met with Turkish President Erdogan and congratulated Fayez Al-Sarraj, head of the Libyan National Government in Tripoli, for his military win against General Heftar’s forces in Benghazi, breaching Tunisia’s policy of neutrality and drawing Saied’s rebuke. Two no-confidence motions against him nearly passed amid heated debates. Public protests against Ennahdha surged, with demonstrators blaming the party for corruption and the country's economic stagnation.

Frustration hit its peak in the summer of 2021 during the COVID-19 crisis when, as hospitals overflowed, Ennahdha’s number two, Abdelkarim Harouni, demanded that Saied pay $900 million to party members victimised by the dictatorship—a demand that further enraged an already exasperated public. Saied, too, had enough.

In the following days, Saied initiated a vast economic and political purge that has all but ended Tunisia’s brief experiment with democracy. Over 500 businessmen were arrested in the following days, including Nabil Karoui and oligarch Marwen Mabrouk, Ben Ali’s former son-in-law and owner of a major industrial group. The charges ranged from corruption to tax evasion and various economic crimes.14 Former ministers and political figures were also detained, notably Rached Ghannouchi and Ali Larayedh of Ennahdha, Abir Moussi of the PDL (pro–Ben Ali party), and former Prime Minister Youssef Chahed. Journalists and members of civil society were arrested on charges related to foreign funding.15

With full powers at his disposal, Saied was now free to implement his project for a complete overhaul of the Tunisian state. In 2022, he submitted a new constitution to a referendum, which passed with 94% of votes. Its legitimacy has been called into question owing to a record-low voter turnout of 30%, triggered by opposition calls to boycott the referendum.

Saied Reforms Tunisia’s Political Economy

When Said was elected into power in 2019, he faced a country mired in chaos and stagnation. Between 2011 and 2019, Tunisia’s public debt had risen from 40% to 70% of GDP, while external debt reached the same level. Rating agencies repeatedly downgraded the country’s sovereign rating. Inflation stood at 6.5% at the time of Saied’s election.16

Saied’s mandate was marked by a further series of external shocks and structural challenges that worsened the economic crisis: the COVID-19 pandemic, the collapse of tourism, the war in Ukraine (upon which Tunisia heavily depends for its wheat imports), a historic drought that reduced harvests and water resources, a migration crisis, and internal political turmoil. The country’s financial situation worsened with runaway inflation and strained public finances.

In Search of Financial Sovereignty

Facing the imminent risk of default on external debts contracted after 2011, the government turned in 2022 to the IMF for a loan of $1.9 billion. However, the IMF wanted to impose a shock therapy package. Saied rejected this, denouncing the IMF’s neoliberal prescription that had repeatedly failed Tunisia for 40 years, and walked away from the negotiations. This triggered a further downgrade of the country’s credit rating, then classified as ultra-speculative. The IMF closed its office in Tunisia in February 2025.

Contrary to analysts’ predictions, Tunisia avoided default by banking on its financial autonomy. Saied’s government sought local banks’ support and issued Treasury bonds on the domestic market, allowing it to repay several major maturities: the Eurobonds and other loans contracted between 2014 and 2018, as well as the IMF instalments due in February and October 2024. In January 2025, it even managed to honour the country’s largest Eurobond ever (amounting to $1 billion), and only one final eurobond remains to be repaid in July 2026, after which nearly all external debt in financial markets will be settled, with only multilateral external debt remaining.17

Inflation, which had reached 10% in 2023, fell to 5.7% in February 2025. External debt was reduced from 70% of GDP in 2019 to 42% in 2025. Public debt was brought under control and the deficit was reduced from 8.4% to 5.4% in 2024. In response, rating agencies improved their evaluation of the country.

Wishing to reduce its dependence on external borrowing, Saied plans to end the independence of the Central Bank, which he considers disconnected from Tunisia’s economic reality (with its key interest rate at 8% despite falling inflation). He intends to align it with his developmentalist policy, compelling public and private banks to provide more credit to finance productive investments and infrastructure.18

Infrastructure & Industrial Production

Contrary to the IMF’s advice, Saied rejected the privatisation of public enterprises, arguing that they must be reformed and made competitive in the market. He is betting on reviving national production to restore the country’s economy. To contribute to that, Saied has banned the practice of subcontracting in favour of long-term employment contracts for all, with a few exceptions.

“The state must return to steel. We want to build our country with our own resources, through our own choices, on our own, and we will not sell our country to anyone," declared Saied, emphasising the country’s turn to developing its natural resources and industrial production as a path to political sovereignty.19 Saied has also forced the restarting of Tunisia’s phosphate industry—which had been halted for 10 years due to social turmoil and labour strikes—and is on track to produce 5 million tonnes of phosphates by 2025 and 14 million tonnes by 2030.20

Saied has also introduced community enterprises, inspired by Chinese TVEs: rural collective enterprises, which group residents of a given locality or region on a development project, mainly in agriculture and rural industry. To encourage these initiatives, the Tunisian state provides residents with public agricultural land, 10-year tax exemptions, and low-interest loans. This reform aims to stimulate regional development, exploit the state’s arable land to strengthen food sovereignty, foster grassroots industrialisation, and reduce unemployment.21 However, this model has not gained much traction owing to administrative hurdles (some caused by Saied’s own ministers who are not convinced by the project), poor communication about its benefits despite its success in China, and fears of reviving the collectivist policies of the 1960s.22

Faced with an excessive dependence on the European market (75% of Tunisian exports are destined for the EU), Saied has also launched a new commercial strategy by diversifying economic relationships with emerging powers like Russia, India, Brazil, Indonesia, Pakistan, and Iran, and strengthening cooperation with China, Saudi Arabia, Japan, South Korea, and the USA.

Energy and environmental projects include the installation of four photovoltaic plants with a total capacity of 500 MW (in collaboration with Japan), as Tunisia seeks to deliver an ambitious 35% of its energy needs through renewables by the end of the decade.23

There are ongoing negotiations to achieve electrical interconnection with Italy, Algeria, and Libya, which would not only stabilise Tunisian citizens’ access to electricity at cheaper rates but also improve Tunisia’s industrial competitiveness as the cost of energy is a key input into industrial production.24

The Tunisian government is also building three desalination plants with four more in the pipeline, totalling 16 operational plants that provide 6% of Tunisia’s potable water. The government has an ambitious goal of seeing 30% of Tunisia’s potable water needs provided through desalination by 2030.25 In further efforts to combat drought and water scarcity in the country, the government is exploring cloud seeding programmes in collaboration with the American University of Wyoming26 and the Indonesian government.27

Historically, the central and southern regions of the country have suffered from underdevelopment and a lack of infrastructure compared to Tunis and the northeastern coastal regions. As part of his project to overhaul the state, Saied has initiated significant infrastructure projects aimed at modernising Tunisia and reducing regional inequalities. Ongoing projects in the transport and mobility sector include the construction of a 10km-long bridge in Bizerte (in collaboration with China)28, the development of the country’s largest highway connecting Tunis and Jelma, and the finalisation of the Gabès–Ras Jedir highway leading to the Libyan border. Additionally, two high-speed railway lines are set to launch in Tunis, the construction of the Sfax metro has begun, and the railway network is undergoing modernisation.

Reforming the State

Parallel to managing the economic crisis, Saied has embarked on a complete overhaul of the Tunisian state. His new constitution established a “decentralised democracy” organised into 279 local councils, 24 regional councils, 5 districts, and a National Council of Regions and Districts. These entities enjoy administrative and financial autonomy, with the power to levy local taxes and responsibility for the economic development of their territories. The National Council of Regions and Districts is expected to finalise a development plan for 2026–2030 to revitalise growth and reduce regional disparities.

Saied is planning sweeping reforms to public administration to make it more efficient by reducing the bureaucratic complexity of existing structures. The eight agencies responsible for investment and exports have been merged into a single entity. Saied has moved to limit the system of authorisations in strategic sectors to facilitate productive business and investment. And, crucially, Saied has implemented ‘fiscal justice’ to reduce rent extraction in the economy by taxing rents and other forms of unproductive wealth with the 2025 Finance Law, which has also reformed personal income and corporate taxes to improve domestic borrowing and reduce external debt.29

Saied has also attempted to accelerate the pace of reforms and their adoption by applying pressure on ministers and civil servants and trying to create a results-and-deadline-oriented culture. However, reforming the culture of lethargy in Tunisia’s public sector may prove the most difficult obstacle to overcome, and directly impacts attempts at formulating and executing policy across the range of issues that Tunisia faces.30

Gambling on Development

Saied’s gamble is that development comes first, and that if Tunisia’s economy continues to flail from IMF reform programme to IMF reform programme, there is little hope for a stable democratic transition. His abortion of Tunisia’s failed experiment with democracy and concentration of political power in himself as President aims to achieve nothing less than the reformation of Tunisia’s political economy.

Eliminating Tunisia’s external debt, unlocking more credit for agricultural production, and launching infrastructure projects are positive steps being taken to reform the Tunisian economy. Additionally, Saied understands the importance of state capacity and investment to achieve development, rather than gutting public services and investment as the IMF (and other international financial and economic institutions) have recommended to Tunisia and other developing economies—with few successes.

For now, Tunisia’s economy seems to be stabilising, although long-term challenges remain. High youth unemployment and low wages persist. The volatility of the price of raw materials threatens Tunisia’s trade balance, which remains highly vulnerable to external trade shocks. Saied is in a race against time as short-term measures to shore up the Tunisian economy fail to yield long-term economic growth, making the acceleration of expected reforms and the implementation of the 2026–2030 plan essential to avoid another political quagmire.

The popular reception of Saied’s reforms has been mixed. Those advocating for a more politically and economically sovereign Tunisia with a strong welfare state have welcomed them, while others oppose these measures, primarily because of Saied’s autocratic turn. Among his supporters, some see Saied’s autocratic executive style as a welcome turn from the post-2011 parliamentary chaos and paralysis, as well as a departure from the policies of the last 40 years. However, for others, the uncertainty and lack of clarity in Saied's communication have led to a lack of trust in his claims of reform.

Saied faces the daunting challenge of contending with an administration resistant to change, which is slowing down crucial reforms. His political isolation, lacking both a party and an influential network, further complicates his task. Without strong media allies or an extensive network, Saied struggles to control the narrative both domestically and internationally. Meanwhile, public impatience with the slow economic recovery is growing, and many may tire of his anti-corruption and populist rhetoric, especially as the increasingly sensitive migration crisis has added more political pressure on the Tunisian government.

2025 will be a decisive year for Saied: as popular patience wears thin, his gamble to radically reform the state and implement development policy must yield tangible results and lead to an economic recovery. Should he fail, his legacy will be the re-entrenchment of autocracy in Tunisia without economic development.

A trial that just concluded in February 2025 sentenced eight to death, associated with ISIS, for the murder of one of these MPs: “Eight sentenced to death for 2013 murder of Tunisia opposition leader”, Arab News, 2025

Very hard to find comprehensive and well sourced summaries on Tunisia current direction - very well done and thank you for this.