Qatar’s Gas-Powered Statecraft Reaches New Heights

How Qatar’s leadership used its vast energy resources to transform the emirate from an isolated backwater into a global brand and diplomatic heavyweight.

Humble Origins

Qatar, a nation of just 2.8 million inhabitants, of which 350,000 are citizens, has leveraged its vast natural gas reserves to ascend from regional obscurity to global relevance. With one of the world’s highest GDPs per capita exceeding $80,000 in 2024, its trajectory has been defined by strategic resource exploitation, audacious diplomacy, and soft power investments. Qatar has become a global brand, buying European palaces, luxury hotels, football teams and hosting the World Cup. Its diplomatic network thrives, and it is a preferred mediator in political conflicts from Gaza and Israel to US negotiations with the Taliban in Afghanistan and with Iran, and mediating internal conflicts in Sudan and Syria, among others. The emirate has transformed itself from a mere Saudi-aligned protectorate to a sovereign state with its own regional influence while adapting through periods of revolution, regional rivalries, dynastic successions, and attempted coups.

Qatar’s path to global eminence began in February 1995, when Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani orchestrated a bloodless coup against his father, Sheikh Khalifa bin Hamad Al Thani, who was on an official visit abroad. Sheikh Khalifa had prioritised preserving Qatar’s traditions and “national identity”, and was reluctant to commit the country to an ambitious and necessary modernisation. His son and the new emir, Hamad, recognised that Qatar’s survival hinged on leveraging its hydrocarbon wealth to secure domestic prosperity and international relevance. The alternative was to become a mere puppet state of its larger neighbour, Saudi Arabia.

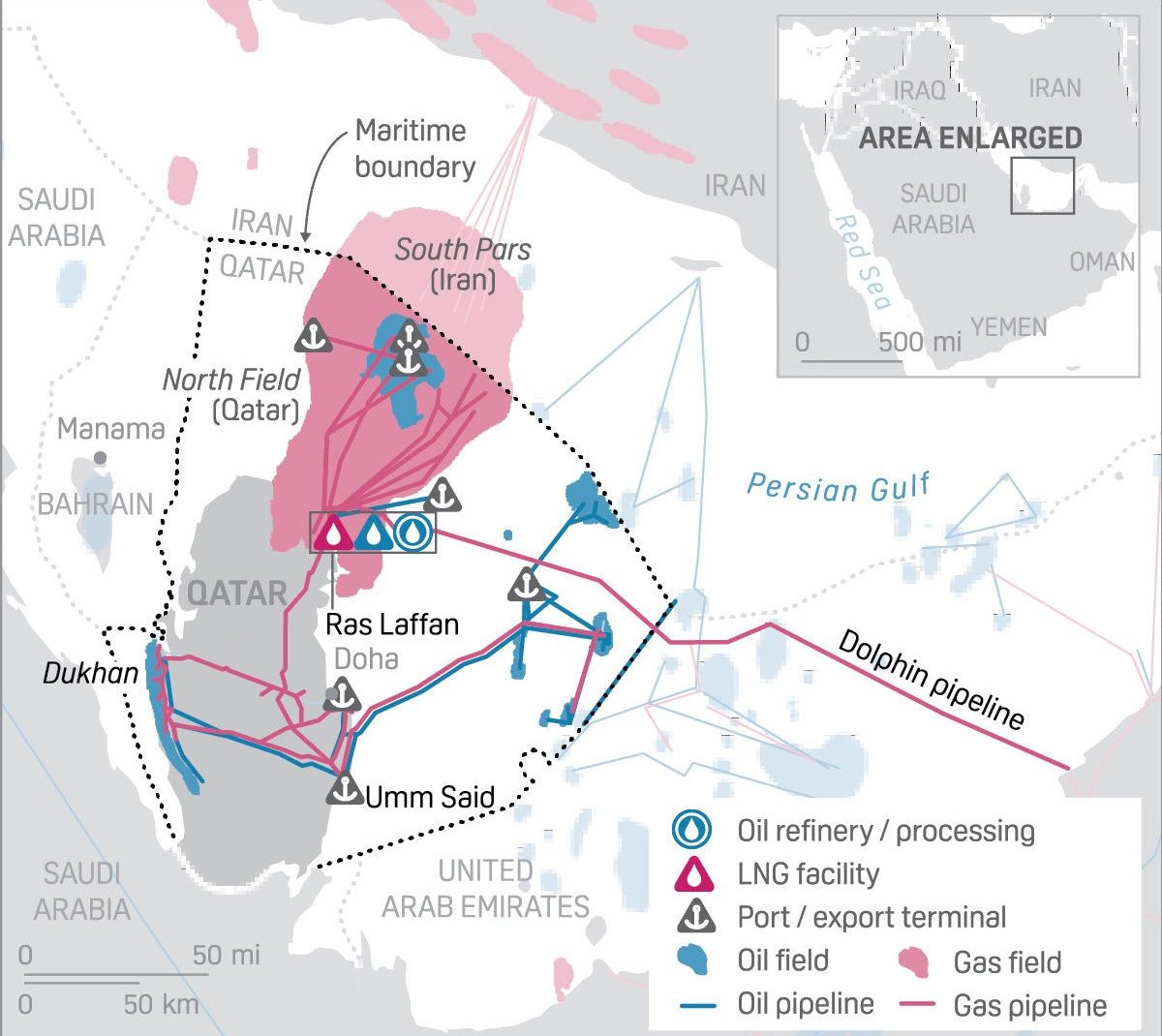

Emir Hamad’s desire to transform Qatar from a peripheral Gulf state to a global power would depend on systematically exploiting its North Field gas reserves. This reservoir, shared with Iran and holding over 900 trillion cubic metres of natural gas (approximately 20% of global reserves), became the cornerstone of the nation’s economic and strategic ambitions. Aware of the economic potential of the massive North Field, Emir Hamad commenced the export of liquefied natural gas (LNG) to Japan in 1997, Qatar’s inaugural client and Asia’s largest LNG importer at the time. Since then, Qatar’s revenues from LNG exports surged rapidly, reaching $26 billion annually by 2010.

These revenues have been assiduously invested into infrastructure development: modern transport infrastructure such as airports, railways, and roads; hospitals; a European-style social safety net for Qatari citizens, and even the construction of Education City, under the Qatar Foundation, hosting satellite campuses for seven elite American universities, including Carnegie Mellon, Georgetown, and Northwestern. Thanks to these investments, the local population, barely 100,000 native citizens in 1990 and now around 380,000, enjoys a standard of living higher than that of the wealthiest Western nations.

Regional Arab powers like Saudi Arabia and Egypt opposed the new Qatari emir Hamad’s desire for independence, exemplified by his decision to export LNG. On 14 February 1996, supporters of the former emir launched a counter-coup against Hamad, backed by Saudi Arabia and Bahrain. Qatar’s intelligence services narrowly thwarted this coup plot. The region was seemingly too small for Emir Hamad’s ambitions for Qatar. To secure his country’s future and assert its independence against its neighbours, he launched an ambitious strategy that, alongside LNG exports, sought to cultivate Qatar’s soft power and secure the country through a military alliance with the world’s pre-eminent power, the United States.

Emir Hamad launched Al Jazeera on November 1, 1996. Inspired by the CNN model, Al Jazeera was the first 24-hour news television network in the Arab world, creating an unprecedented space for freedom of expression and opinion in the region. The network also became Qatar’s preferred tool for projecting its voice and shaping its image on the global stage. Al Jazeera would later become a megaphone for the Arab Spring, becoming synonymous with the aspirations of the Arab street and revolutionary fervour against Arab regimes.

Qatar’s previous emir, Khalifa, had signed the 1992 Defence Cooperation Agreement with the United States, which included constructing Al Udeid Air Base near Doha. Eventually built by Emir Hamad in 1996, the base gradually expanded to become the largest US base in the Middle East, hosting one of the region's largest contingents of the US Air Force. Under this imperial security umbrella, Qatar sought to consolidate internal stability, diversify its regional partnerships, and arbitrage American protection to execute its strategic agenda.

Alongside Emir Hamad, his cousin, Sheikh Hamad bin Jassim Al Thani (“HBJ”), played a fundamental role in shaping Qatar’s soft power strategy. HBJ was appointed Minister of Foreign Affairs in 1992 and became Prime Minister in 2007, holding two of the highest offices in the Qatari state. Qatar became an increasingly proactive diplomatic player during HBJ’s tenure, positioning itself as “a dialogue partner to all sides” and an impartial mediator in regional conflicts.

In 2008, HBJ brokered a narrow escape for Lebanon from a new civil war by bringing together Lebanese leaders and factions, including Hezbollah, Sa’ad Hariri, and Walid Jumblatt, leading to the signing of the Doha Agreement. In the Horn of Africa, Qatar was decisive in mediating tensions between Eritrea and Djibouti after the 2008 border conflict, sending envoys and supporting peace negotiations. In Sudan, Qatar facilitated dialogue between the Sudanese government and Darfur rebels, hosting talks in the Qatari capital, Doha, and helping secure temporary ceasefires.

In the early 2000s, Qatar established unofficial, and later formal, commercial relations with Israel by opening reciprocal trade offices, well before the signing of the Abraham Accords. Qatar’s pragmatic statecraft was embedded in its DNA, as the emirate cultivated relations not only with the US, Israel, and Europe but also with Hamas, Hezbollah, Iran, and Syria, turning Doha into a regional hub for negotiation between friends, enemies, and everyone in between.

The Qatar Investment Authority Turns Energy into Soft Power

In 2005, Qatar created its first sovereign wealth fund, the Qatar Investment Authority (QIA), led by HBJ. With an initial capitalisation of $25 billion, pursuing financial returns was not strictly their mandate. QIA had a dual objective: to prepare Qatar’s economy for the post-hydrocarbon era, and to strengthen the country’s cultural influence through strategic soft power investments. To achieve this, capital allocation was split between investing in companies for their brand image and acquiring iconic assets in Western capitals.

QIA’s most significant opportunity would come following the 2008 financial crisis, when European governments raced to attract QIA’s investments to revive their recession-hit economies. Then-president Nicolas Sarkozy of France went as far as introducing a capital gains tax exemption on real estate investments by Qatar and its nationals, effectively transforming the country into a fiscal haven for Qatari investments.

QIA made several high-profile acquisitions, such as in Paris, where they acquired the Peninsula hotel ($750 million), the Le Royal Monceau palace ($250 million), and the iconic Printemps department stores ($1.6 billion). QIA also made several investments across the channel. In 2010, they bought the Harrods department store in London ($1.6 billion), a symbol of British luxury consumption, and in 2012, invested $1.5 billion in The Shard skyscraper.

Beyond real estate, QIA made significant investments in major European companies, such as Volkswagen and Porsche ($7 billion), LVMH ($600 million), Total ($2 billion), EADS, Barclays ($4 billion), and the Accor hotel group. This diversified QIA’s portfolio and embedded the Qatar national brand into some of Europe’s, and by extension the world’s, most prestigious companies, brands, and cities.

QIA also invested significantly in developing its national airline, Qatar Airways, to position Doha as a strategic transport hub between Europe, Asia, and Africa. Thanks to its modern fleet and outstanding service, the airline has become a major player in international air transport, further enhancing Qatar’s global visibility and influence. In 2024 alone, Qatar Airways generated $25.5 billion in revenue, operating a fleet of over 290 aircraft and transporting over 43 million passengers. The company was recently ranked the world’s best airline for the eighth time.

With the advice of ex-French president Sarkozy, QIA, through its subsidiary Qatar Sports Investment (QSI), acquired the French football club Paris Saint-Germain for $40 million in 2012. It is now valued at $4 billion and is a successful flagship European football club. Franco-Qatari deals have gone further: in return for arms purchases, particularly for the purchase of the French defence company Dassault’s Rafale fighter jets, Sarkozy actively championed Qatar’s bid to host the 2022 FIFA World Cup, personally lobbying Michel Platini, then president of UEFA. Qatar was granted the bid in November 2010.

Qatar has made education and culture central pillars of its soft power through the Qatar Foundation, with a hefty $17 billion endowment. Founded and led by Sheikha Moza, Emir Hamad’s wife (and mother of the current emir, Tamim), the foundation’s $1.5 billion investment in Education City attracted several prestigious American universities. Qatar has also promoted art, becoming a central player in the art market with high-profile acquisitions such as Mark Rothko’s “White Center” ($72.8 million), Paul Cézanne’s “The Card Players” ($250 million), and constructing museums such as the Museum of Islamic Art and the National Museum of Qatar.

Under the leadership of Emir Hamad and HBJ, Qatar had been transformed into an increasingly consequential diplomatic mediator, with its influence visible on European skylines and on televisions across the Arab and Muslim world through Al Jazeera. Perhaps then, they felt secure enough to leverage Qatar’s wealth and status on the next great gamble: The Arab Spring.

The Megaphone of the Arab Street

The early 2010s marked Qatar’s most audacious, but ultimately overextended, phase of geopolitical adventurism. Buoyed by recent international successes and emboldened by its maturing soft power infrastructure, the emirate, under Emir Hamad and HBJ, sought to exploit the Arab Spring uprisings to redraw the Middle East’s political map.

From the outbreak of protests in 2011, Qatar adopted an unambiguous stance: supporting the forces of change, particularly movements affiliated with the Muslim Brotherhood, while deploying aggressive media strategies through Al Jazeera and unprecedented financial interventions. This ideological and strategic choice reflected Doha’s ambitious vision of cultivating a new generation of Arab governments aligned with its interests.

Qatar emerged as the Muslim Brotherhood’s principal patron in Egypt, providing Mohamed Morsi’s government with $3 billion in bonds to stabilise the faltering pound. Al Jazeera’s Arabic channel amplified this support, dedicating much of its Egypt coverage to pro-Brotherhood narratives during this period.

Qatar’s interventions assumed military dimensions in Libya and Syria. During NATO’s 2011 Libya campaign, the Qatari armed forces deployed Mirage fighter jets to support sorties against Gaddafi’s troops. It also sent officers to train Libyan fighters and funnelled $400 million to militias such as the Libya Shield Force. In Syria, Qatar coordinated arms shipments to several groups fighting Bashar al-Assad’s forces.

Al Jazeera played a central role as Qatar’s ideological conduit. The channel granted platforms to opposition figures and shaped revolutionary narratives across the region, transforming Qatar into the Arab Spring’s symbolic patron within months of the uprisings. This positioned the emirate in direct opposition to historical regional powers such as Egypt, Syria, and Saudi Arabia, who viewed the protests as existential threats to their stability. Qatar’s support for the Brotherhood extended beyond the Arab world, cultivating ties to Brotherhood-affiliated European organisations, notably in the United Kingdom and France. This interventionist foreign policy aimed to position Qatar not only as a regional power but as a global patron of political Islam, blending ideological alignment with soft power projection.

While the initial phase of Qatar’s strategy bore fruit, with electoral successes for Brotherhood-affiliated parties like Rachid Ghannouchi’s Ennahda in Tunisia, Muhammad Morsi’s Freedom and Justice in Egypt, and Justice and Development in Morocco, the structural weaknesses of these movements, often ill-prepared for governance, quickly became apparent. Their lack of experience, internal divisions, and tensions with other political forces undermined their legitimacy.

At the same time, regional rivals like Saudi Arabia and the UAE were preparing a counter-revolution through a diplomatic, financial, and media offensive that would stem and eventually reverse the tide of the Arab Spring and Qatar’s regional ambitions.

The Counterrevolution Strikes Back

Aware that the tides were shifting and eager to preserve the achievements of his rule since 1995, Emir Hamad made a strategic decision: in June 2013, he abdicated in favour of his 33-year-old son, Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani. This transition marked a turning point in Qatari policy. HBJ, regarded as the principal architect of the previous years’ diplomatic activism, was sidelined by Emir Tamim and forced to resign as prime minister. However, he retained control of QIA until 2017.

Emir Tamim’s inaugural speech in June 2013 emphasised “stability through balanced relations”. This new policy prioritised domestic security and economic resilience over ideological adventurism, signalling a decisive break from his father’s alignment with the Muslim Brotherhood. The appointment of Abdullah Bin Nasser Al Thani as Prime Minister, concurrently holding the interior ministry portfolio, underscored this inward focus, reflecting a recalibrated statecraft centred on insulating Qatar from regional turbulence. Tamim’s rhetoric struck a deliberate tone of neutrality: “We respect all influential and active political trends in the region, but we do not belong to one current against another. We are Muslims and Arabs who respect the diversity of currents and religions at home and abroad. [...] We are a coherent state, not a political party. That is why we seek to maintain relations with all governments and states.”

Qatar’s recalibration faced immediate tests. Mere weeks after Tamim’s ascension, Saudi Arabia and the UAE intensified their counter-revolutionary campaigns. In July 2013, Abu Dhabi signed a $4.9 billion aid package to Egypt’s military, directly facilitating President Mohamed Morsi’s ouster by General Abdel Fattah El-Sisi. By 2014, Tunisia’s Ennahda, a key Qatari ally, succumbed to pressure to relinquish power, while in 2015, Russia’s military intervention in Syria turned the tide against Syrian opposition groups.

Meanwhile, Saudi Arabia orchestrated a GCC-wide designation of the Muslim Brotherhood as a terrorist organisation in March 2014, diplomatically isolating Qatar within the Gulf Cooperation Council. These cascading setbacks forced Tamim’s government to distance itself further from political Islam. By December 2014, several Brotherhood figures were quietly expelled from Doha. Al Jazeera cancelled programmes like “Sharia and Life” and reduced Brotherhood-affiliated airtime to a bare minimum. Qatar pivoted towards discreet mediation, positioning itself as a neutral intermediary in talks between the Taliban and the United States, Israel and Hamas, and the US and Iran. However, regional rivals dismissed this shift as cosmetic.

In June 2017, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Egypt, and Bahrain, emboldened by US President Donald Trump’s tacit support, imposed a comprehensive land, air, and sea blockade on Qatar, which they accused of maintaining ties with Iran, sponsoring terrorism, and propagating subversion through Al Jazeera.

Qatar’s Strategic Pivot

The blockade was a revelatory moment for Qatar, revealing the limitations of its reliance on financial might and media influence. Despite colossal financial capital and investments, possessing the world’s highest GDP per capita, an extensive diplomatic network, solid military partnerships (particularly with the United States through Al-Udeid), and a powerful media empire embodied by Al Jazeera, the emirate remained fragile when faced with coordinated pressure.

The blockade, which lasted four years and ended in 2021, provoked an antifragile response, demonstrating Emir Tamim’s retention of the same adaptive capacity that has defined the emirate’s leadership since his father, the former Emir Hamad, took power in 1995. Qatar diversified its security dependencies, accelerating security cooperation with Turkiye, which deployed 5,000 Turkish troops to Al-Udeid Air Base. Qatari companies like the conglomerate-owned Baladna helped the emirate achieve food self-sufficiency. Two years after the blockade was imposed, Qatar produced 95% of its dairy needs by 2019. Qatar has also developed alternative transport routes, such as redirecting air flights through Iran.

Qatar has not entirely abandoned its regional ambitions. Instead, it adopted a more circumspect diplomacy, marking a definitive departure from the flamboyant "chequebook diplomacy" and ideological alignments of the HBJ era to a quieter, more systematic approach where discretion, deeper bilateral relations, and methodical lobbying in global centres of power, particularly in Washington, D.C., take precedence. This shift has seen Qatar re-emerge after 2021 as a pivotal mediator in conflicts from US-Taliban talks to Gaza ceasefire negotiations, even as it navigates the enduring tensions of Gulf and Arab rivalries.

Since 2017, Qatar has reportedly spent nearly $225 million with 18 lobbying and public relations firms in the United States, more than triple what Israel invested in the same domain over the same period. This strategy primarily aims to counter the effects of Israeli lobbying and anti-Qatar groups in Washington, while strengthening strategic ties with American political elites. Between 2019 and 2023, Qatar provided at least $9 million in funding to several prominent Washington-based think tanks, including $6 million to the Brookings Institution, $2.3 million to the Stimson Centre, $300,000 to RAND, and $380,000 to the Middle East Institute.

Qatar has established relationships with key figures in the American administration, targeting a list of 250 people close to President Trump. These figures have included, for example, Pam Bondi, who served as Florida’s Attorney General before joining Donald Trump’s circle; Susan Wiles, who became the president's Chief of Staff; and Kash Patel, a Trump ally who briefly led the staff at the Department of Defence. In 2017, the emirate hired Stonington Strategies, led by Nicolas Muzin, a former advisor to Republican Senator Ted Cruz known for his pro-Israel stance. Muzin then organised visits by influential figures from the American Jewish community to Qatar, including Morton Klein, president of the Zionist Organisation of America, who until then had been critical of the Qatari regime.

Qatar also briefly collaborated with Lexington Strategies, led by Joey Allaham, a Syrian-American businessman well-connected in pro-Israel circles. Allaham facilitated strategic meetings with the American Jewish community and pro-Israel Republican figures, and helped soften Qatar’s image in American political and religious spheres, particularly around the organisation of the 2022 World Cup. Under the Biden administration, Qatari influence reached a new high by being granted Major Non-NATO Ally status.

But to truly access the inner circle of power, the emirate realised it also had to speak the language of business. A notable episode occurred in 2017, just before the blockade began: Charles Kushner, father of Jared Kushner (advisor and son-in-law to Donald Trump), sought Qatari funding to bail out a troubled New York property at 666 Fifth Avenue. The Qatari finance minister, Ali Sharif Al Emadi, declined the offer. A few weeks later, Jared Kushner leveraged his influence in the Trump administration to back the Arab blockade on Qatar. Qatar learned from this episode: transactions were the game, and Qatar was well-placed to play.

In 2018, a $1 billion offer was made for a 99-year lease on the same building, through Brookfield Properties, of which QIA owns a 9% stake. Since then, strategic investments in entities linked to Trump have multiplied: $1.5 billion injected into Jared Kushner’s private equity fund and, more recently, in 2023, the $623 million purchase of the Park Lane Hotel in Manhattan from Steve Witkoff, a long-time Trump friend. Meanwhile, real estate projects involving the Trump sons, such as a potential luxury golf project in Qatar, are under consideration.

This diplomacy of influence is not limited to the United States. Qatar is also active in Israel, where several close associates of Benjamin Netanyahu have been mandated to improve the emirate’s image within circles of power. More broadly, Qatar is investing in structuring a network of economic and political elites through the organisation of the Qatar Economic Forum, launched in 2021 in partnership with Bloomberg. Inspired by the Davos Forum and the Saudi FII initiative, this annual event aims to position Qatar as an essential platform for discussion on global economic issues.

Since 2021, Qatar, in strategic partnership with Bloomberg, has also launched the Qatar Economic Forum, which brings together more than 1,000 political leaders, business executives, and investors each year to discuss major economic trends, geopolitical challenges, and technological innovations. The collaboration with Bloomberg has given Qatar a competitive edge in creating both distribution and exclusivity.

Finally, this strategic refocusing is reflected in QIA’s mandate, whose investment policy has become more sober and targeted. Gone are the flashy acquisitions; instead, the focus is on long-term investments in strategic sectors such as technology, energy, and infrastructure. This transformation is also evident in the policy of Paris Saint-Germain, Qatar’s property: no more spectacular signings of ageing stars, the club has refocused on building a more coherent and ambitious team, on the verge of winning its first Champions League, with the final scheduled for 31st May 2025.

The organisation of the 2022 World Cup marked a significant step in this rehabilitation: praised for its organisational quality, festive atmosphere, and impeccable security for visitors, it established itself as one of the most successful editions in the tournament’s history, setting a historic attendance record.

Instead of fighting the tide, Emir Tamim has charted a new course for the Qatari state and reconsolidated its position in the region. In Syria, the emirate has played a central role in helping the new Syrian government get on its feet, such as by financing Syrian government employee salaries. Emir Tamim was also the first head of state to visit Damascus and meet with Syria’s new president, Ahmad Al-Shara. Qatar, alongside Turkiye and Saudi Arabia, has successfully lobbied for the lifting of Western sanctions on Syria. A friendly government in Damascus now delicately balancing an alignment of interests between the West, Turkiye, and the Gulf in support of Syria’s stability and reconstruction, offers Qatar another opening for Qatar to deploy its pragmatic diplomacy and drive the new regional balance of power further in its favour.

In Gaza, Qatar has been the primary mediator in the complex talks between Hamas and Israel, making it one of the few actors that can claim to dialogue simultaneously with Western powers, Palestinian groups, and major Arab capitals. On the bilateral level, relations with Egypt, once icy, have significantly warmed. Qatar has announced an ambitious $7 billion investment plan in the Egyptian economy. In return, Egypt has turned to Qatar to secure its natural gas supply, reducing its energy dependence on Israel. After periods of tension with the Tunisian state following Ennahda’s removal from the political scene, Qatar is mending ties and is now the country’s second-largest outside investor in Tunisia after France.

A New Era or a Temporary Lull?

Qatar’s gas-powered trajectory from Gulf protectorate to a linchpin of global diplomacy has not been smooth. Still, the emirate is now reaping the rewards of its patience and adaptability. Emir Hamad’s systematic exploitation of the North Field and subsequent investments in Al Jazeera, QIA’s global asset portfolio, and a wide-reaching diplomatic network enabled its audacious leap onto the world stage. The Arab Spring’s collapse exposed the fragility of Qatar’s influence and ideological patronage. The subsequent blockade prompted the new Emir Tamim’s pivot from flamboyant chequebook diplomacy to networked realpolitik: forging security ties with Turkiye, mastering transactional lobbying in Washington, and prioritising mediation over factional alignments.

Just five years ago, Qatar was under siege by its neighbours and facing a real prospect of political instability. This month, US President Trump made a joint tour of Riyadh, Doha, and Abu Dhabi, suggesting a detente between these regional rivals. This shift indicates that Qatar can adapt to changes in the political environment, and it is expected that the emirate continues to play a crucial and growing role in global diplomacy. Qatar's next great test will be whether it can direct its agile statecraft to create a post-hydrocarbon economy or amicably resolve latent Gulf rivalries.